After the Second World War, the Institute helped arrange for 50 Greek women to come to Britain for nurse training. In 1955, 41 Queen’s Nurses were appointed to posts abroad. The January 1958 Queen’s Nurses’ magazine listed overseas district nursing services that had started in Malta (1946), Jamaica (1957) ( Figure 2.4), Singapore (1956), Nigeria (1954), Tanganyika (1957) and Kenya (1956) in collaboration with authorities in those countries. Nurses from those countries came to the Institute for training, some returning home and others staying in the UK. Delegations came from France, Brazil, Turkey, India, Greece and Finland to find out more about the administration and training of district nurses in Britain.

In 1948 the NHS began operating and the employment of district nurses fell to local authorities. Local district nursing organisations no longer had a purpose and quickly ceased to exist; however over 50 accredited training centres training 700 nurses a year were still affiliated to the Institute ( Figure 2.5). The Institute finally ceased to offer full training for district nurses in 1968 when the qualification was absorbed into higher education, and the title of Queen’s Nurse lapsed.

The charity was renamed the Queen’s Institute of District Nursing in 1928 ( Figure 2.6) and the Queen’s Nursing Institute (QNI) in 1973 ( Figure 2.7). Today the QNI operates in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. The Queen’s Nursing Institute Scotland (QNIS) is a separate charity with its headquarters in Edinburgh. The Queen’s Institute of District Nursing in Ireland is an affiliated charity in the Republic of Ireland.

The title of Queen’s Nurse (QN) was reintroduced in 2007 as a means of reinforcing the professional identity of community nurses. Today the QN title is no longer restricted to district nurses: any nurse who has worked in the community for 5 years is eligible to apply ( Figure 2.8). The Institute also offers educational bursaries, awards, professional development and financial assistance to nurses in need. The charity also works to influence healthcare policy, supports innovation and practice development, undertakes research, publishes reports on community nursing practice and holds regular educational events, including an annual conference and general meeting for all Queen’s Nurses.

3 Preparation for a learning environment in the community

Shirley Willis, QN

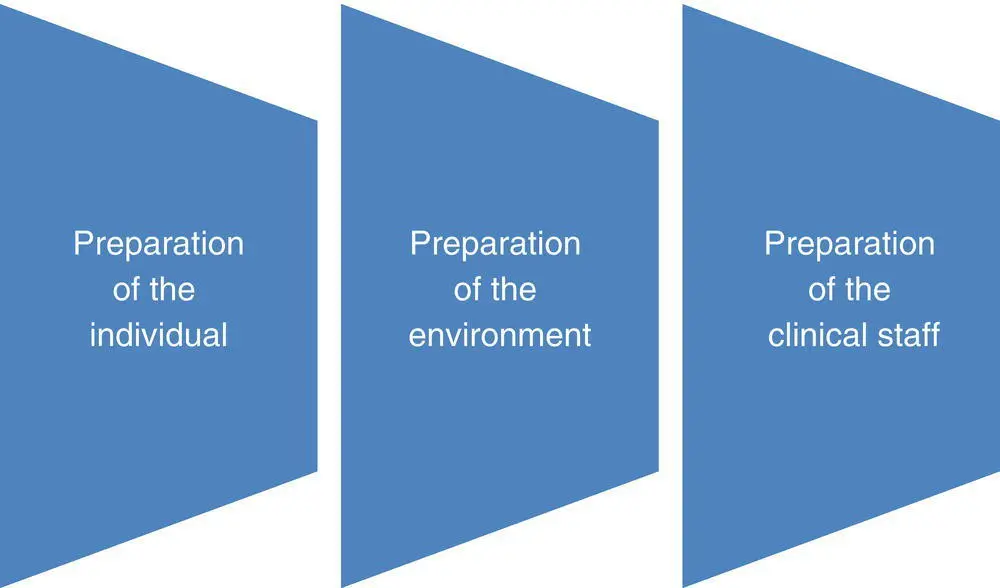

Figure 3.1 The three pillars supporting learning within the community setting.

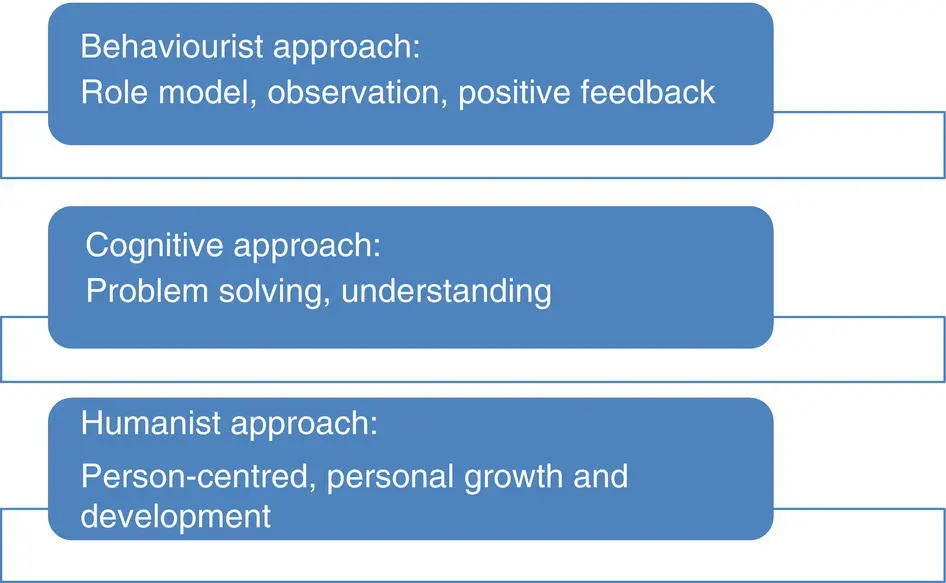

Figure 3.2 Individual learning styles.

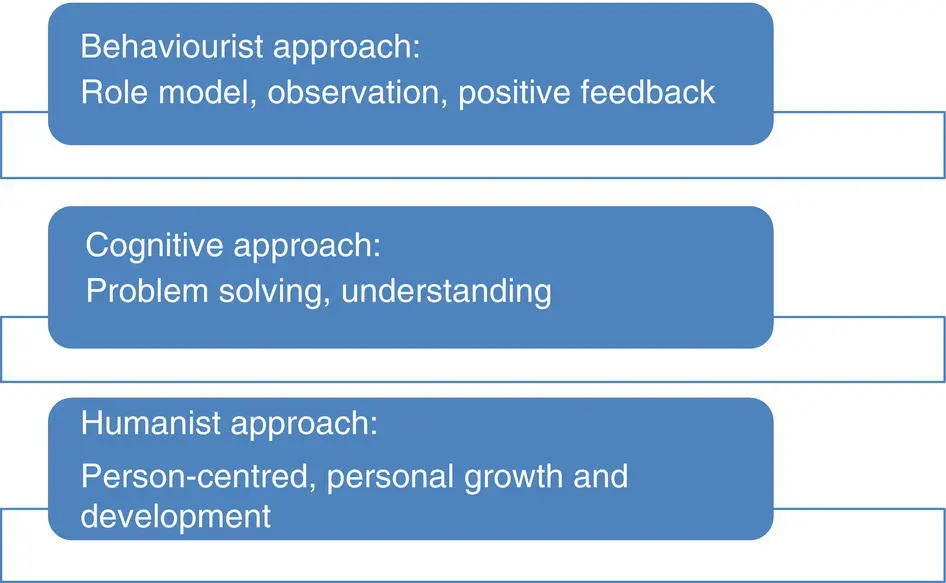

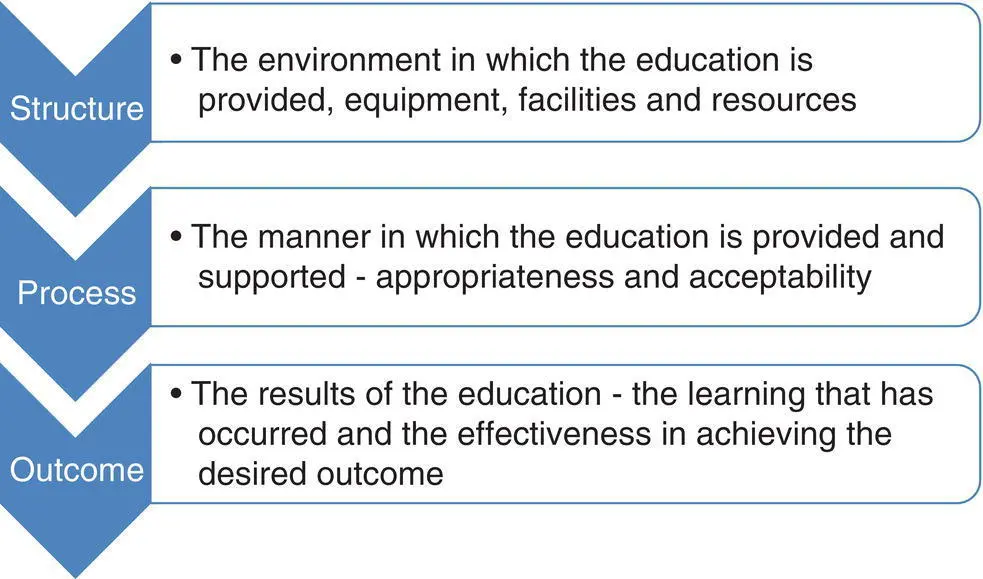

Figure 3.3 Quality in community education.

Table 3.1 Elements contributing to effective clinical supervisor–student relationships.

| Clinical placement supervisor |

Student |

| Identify expectationsProfessional approachSet boundariesDedicated time for the studentCompetence and experienceCredible role modelQuestioningFacilitates learning |

Realistic expectationsProfessional approachWillingness and commitmentReflective learnerSelf‐awarenessUnderstands own learning needsQuestioning |

Caring for patients within their home environment, which could be a private house or a residential or nursing home setting, provides the nursing student with a number of unique learning opportunities. In preparing to learn within this very diverse and often challenging setting, it may be helpful to begin by considering the learning opportunities in terms of the skills that the student may be able to develop:

Communication skills: Talking to patients, family members, carers and other health professionals in an environment where the nurse is the ‘visitor’.

Observational skills: Recognising the challenges that the patient may face in achieving concordance with any identified plan of care.

Consultation skills: History taking and information gathering in order to inform the development of a care plan. It is important to consider the limitations of the environment and the absence of many of the structures and support services that may be taken for granted within the acute healthcare setting in order to inform the plan.

Presentation skills: Presenting information both formally and informally in a manner that can be understood by the particular audience and is appropriate to the setting.

Flexibility, adaptability and competency skills: Being able to carry out skills competently and effectively whilst adapting to the challenges of the environment.

Evaluation skills: Considering outcomes of care in terms of the patient themselves, the delivery of the service in this setting, and in relation to the organisation’s objectives and targets.

Although these skills are all transferable to other healthcare settings, learning within the community setting allows the practitioner to really develop these ‘generalist’ skills towards a more ‘specialist’ level, with clear benefits to patient care.

In order to be able to take full advantage of these learning opportunities, preparing to learn within this generalist/specialist arena will pay dividends in terms of both personal and professional development. Preparation for practice could be considered from a number of different perspectives relating to the individual student, the environment of care, and the clinical staff working in the practice area ( Figure 3.1).

For the individual student, preparing to learn within the community setting may be guided by asking a number of questions:

What are my personal learning and development needs at this point in time?

What is my own learning style ( Figure 3.2)?

What do I understand by the term ‘community’?

What are my expectations of the community setting as an environment for learning?

What knowledge/skills/experience can I bring to the community setting to enhance and maximise my learning experience?

In answering these questions it may be helpful to use a structured framework, such as the Strengths/Weaknesses/Opportunities/Concerns approach, to guide your decision‐making.

It could be argued that any care environment that is clinically effective will also be an effective learning environment. However, a conscious effort is required in order to ensure that a clinical setting provides both students and practitioners with a safe and worthwhile learning experience. In ensuring quality within the learning environment it is helpful to consider the structure, process, and outcome of the learning experience ( Figure 3.3).

In accordance with the Standards for pre‐registration nursing programmes (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2018a), it is a responsibility of the educational provider to ensure that students are provided with the opportunity to experience a wide variety of clinical experiences. Working together with clinical practice partners, students will be able to develop to meet the required standards of performance expected of a qualified nurse. Robust working relationships between educational and clinical staff are fundamental to ensuring that the learning environment is maintained.

Читать дальше