The editor would like to thank the staff of The Queen’s Nursing Institute for their support and encouragement, in particular Dr Crystal Oldman CBE, Dr Agnes Fanning and Joanna Sagnella, QNI Publications Manager, who produced many of the illustrations in this book, and QNI interns Joanna Boughtflower, William Carter, Olivia Hicks, Alice Knapton and Chloe McCallum for their valuable assistance.

The editor would also like to thank Hallam Medical, Malinko, Kate Stanworth, Mark Hakansson, Harriet Stuart‐Jones and the editorial staff at Wiley.

Queen’s Nurses are supported by funding from the National Garden Scheme, a national charity that opens private gardens to raise money for nursing and caring charities. Since 1927 the garden scheme has raised millions of pounds for healthcare in the community.

Introduction to District Nursing

A District Nurse is a specialist generalist nurse in the community, an expert who is accountable at an advanced level of practice.

The District Nurse serves a whole community, holding and being responsible for a large and varied caseload of people with complex health needs, and managing admission to and discharge from that caseload. They are responsible for autonomous clinical decision‐making, deploying a team of regulated and unregulated staff to deliver care in peoples’ homes, and leading all the nursing care required. A community staff nurse is one of the nurses working under the direction of the District Nurse. District Nurses work above all in people’s homes and may give support to staff working in Nursing and Residential Homes too.

A qualified District Nurse is prepared for their role with a post‐registration Specialist Practitioner Qualification in District Nursing (SPQ DN) at a Higher Education Institution. These post‐registration programmes are currently approved and regulated by the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) to ensure consistency and quality of standards for education and practice and to prepare nurses for the role of an autonomous practitioner.

Specialist Practitioner Qualifications are also available in Community Children’s Nursing (CCN), Community Learning Disabilities Nursing (CLDN), Community Mental Health Nursing (CMHN), and General Practice Nursing (GPN), and the NMC is consulting on additional qualifications for other community specialisms (2021).

This book describes some of the most important parts of a District Nurses’ role. It is not intended as an exhaustive or comprehensive list of everything that a District Nurse might be called upon to do, which is always changing and developing. The Covid‐19 pandemic has changed the landscape of nursing in the community profoundly and rapidly, and District Nurses are now caring for many people who are recovering from this novel disease.

The landscape of health services in the United Kingdom is also changing, and there is growing variation between England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. Healthcare policy demands that more care is delivered in people’s homes and communities and a greater reliance on self‐care and the prevention of ill‐health, lessening people’s dependence on hospital services.

It is an exciting time to be a District Nurse, working with people, carers, and families across the life course, helping them to maintain health and independence, in communities in every part of the UK.

1 The early history of district nursing

Matthew Bradby

Figure 1.1 Cartoon of Queen’s Nurses in 1918.

Figure 1.2 Queen’s Nurse with a bicycle, c. 1900.

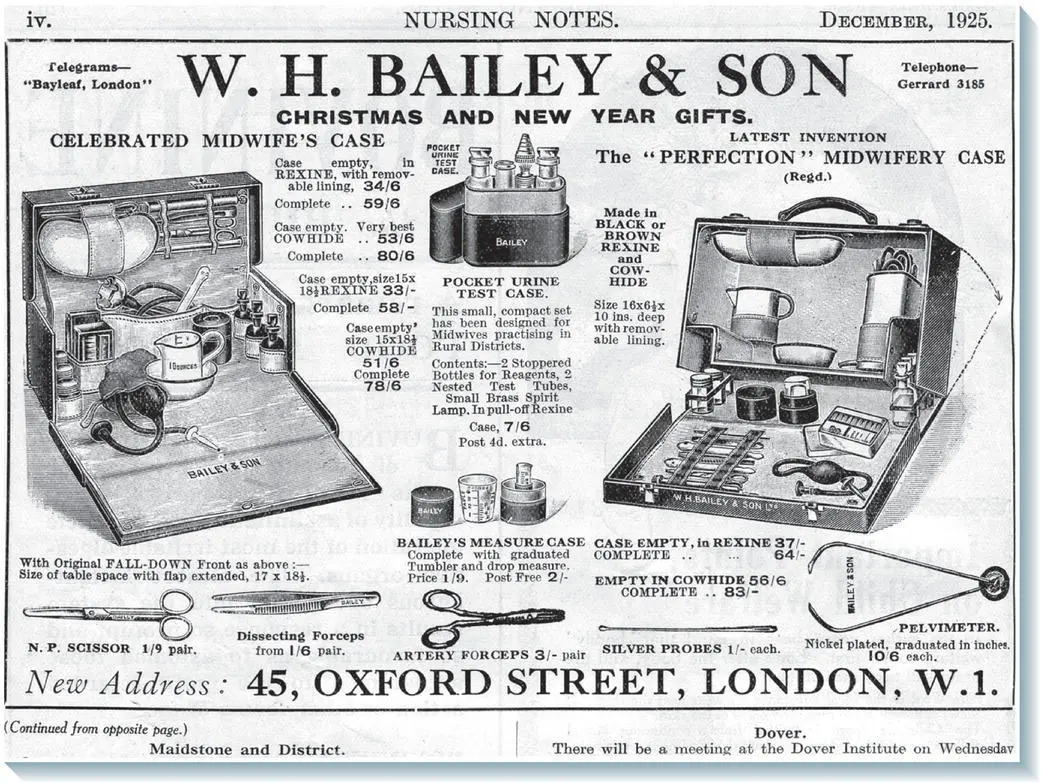

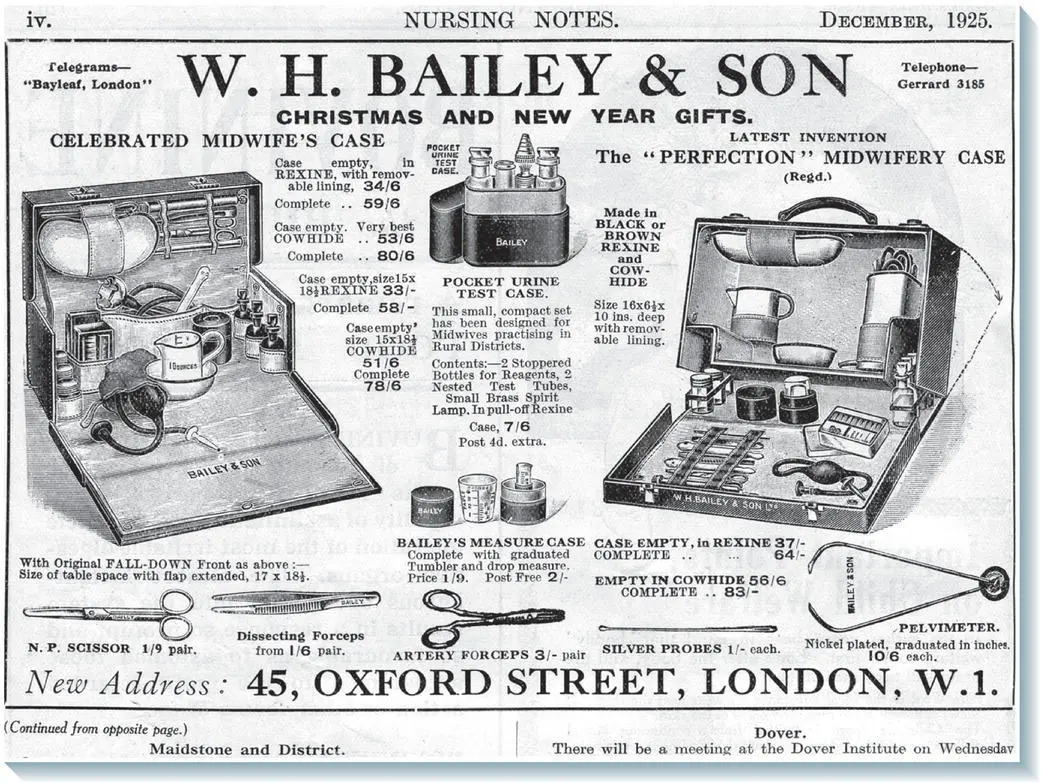

Figure 1.3 The celebrated midwife’s case, 1925.

Figure 1.4 Queen’s Nurses magazine advert, 1913.

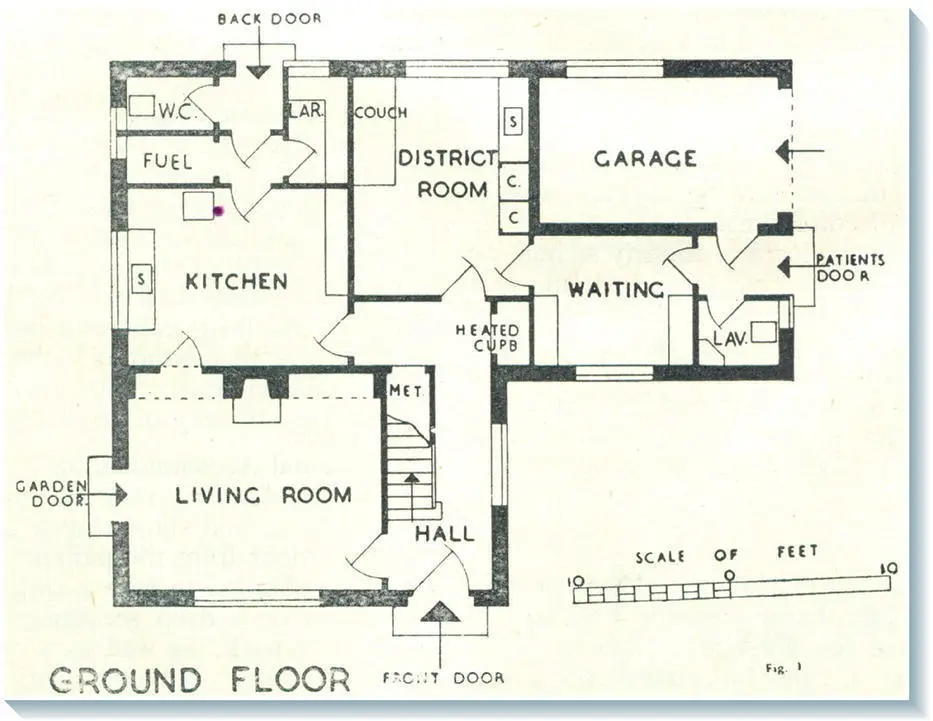

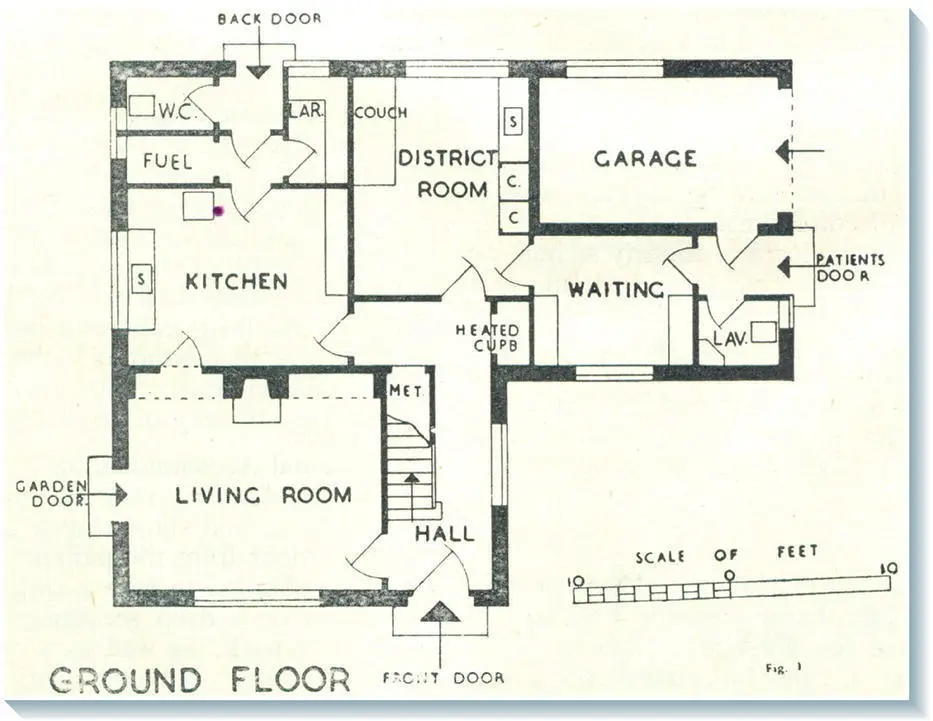

Figure 1.5 Ground floor plan of a district nurse’s cottage, 1945.

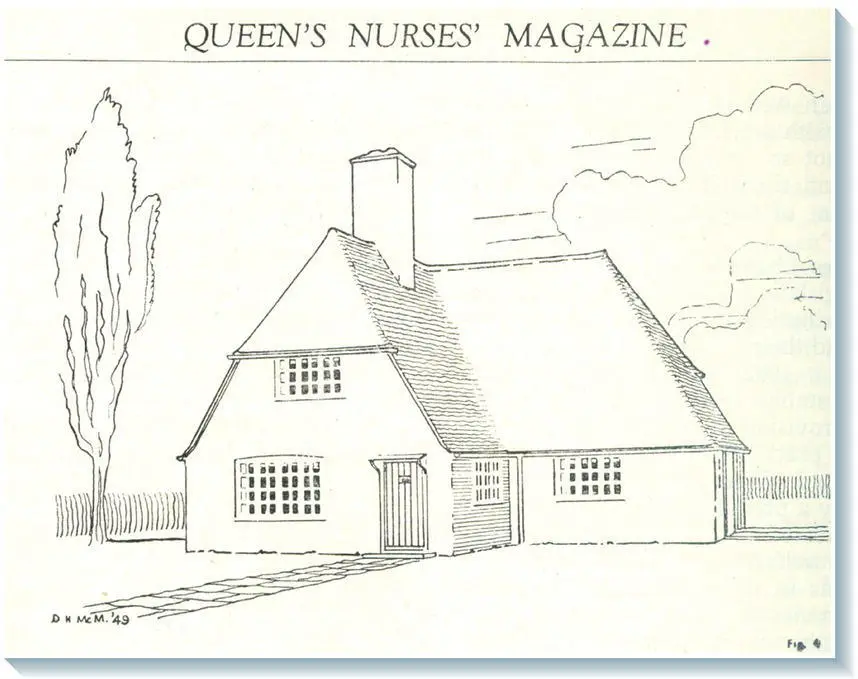

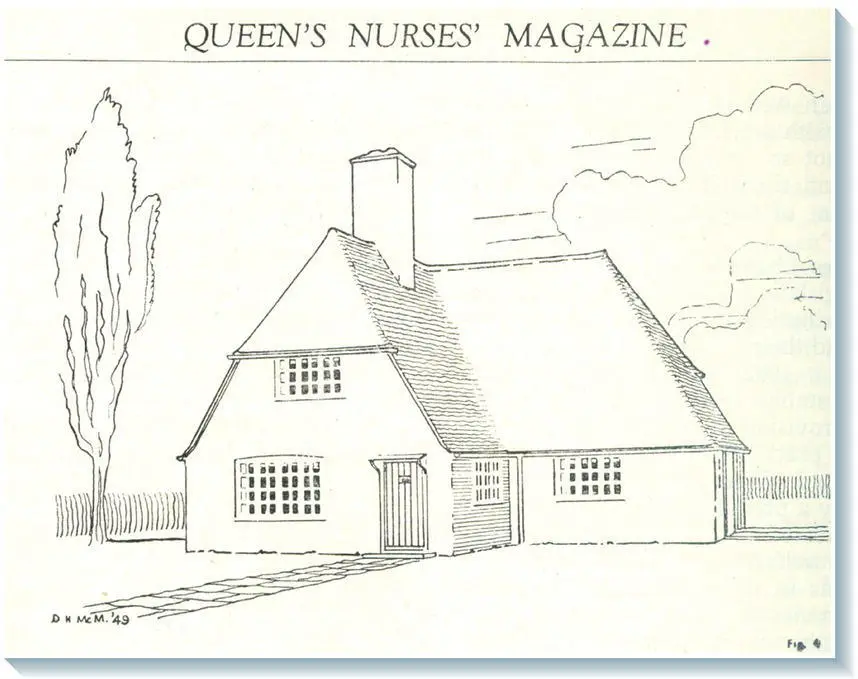

Figure 1.6 Architect’s design for a district nurse’s cottage, 1945.

The district nursing movement started in Victorian England in the mid nineteenth century. The Victorian period was characterised by rapidly growing cities, where many people lived in extremely poor, cramped conditions. Malnutrition and unclean water supplies contributed to severe and regular outbreaks of contagious diseases, such as cholera, typhus and tuberculosis, which were the mass killers of the period. District nursing as an organised movement began when William Rathbone (1819–1902), a wealthy Liverpool merchant and philanthropist, employed a nurse, Mary Robinson, to care for his wife at home during her final illness. In May 1859 William Rathbone’s wife died, and he later wrote:

it occurred to me to engage Mrs. Robinson, her nurse, to go into one of the poorest districts of Liverpool and try, in nursing the poor, to relieve suffering and to teach them the rules of health and comfort. I furnished her with the medical comforts necessary, but after a month’s experience she came to me crying and said that she could not bear any longer the misery she saw. I asked her to continue the work until the end of her engagement with me (which was three months), and at the end of that time, she came back saying that the amount of misery she could relieve was so satisfactory that nothing would induce her to go back to private nursing, if I were willing to continue the work (Hardy, 1981).

William Rathbone decided to try to extend the service started with Mary Robinson, but soon found that there was a lack of trained nurses and that nurse training was disorganised and very variable in quality. In 1860, he wrote to Florence Nightingale, who advised him to create a nurse training school and home for nurses attached to the Liverpool Royal Infirmary and, with typical Victorian organisation and energy, this was built by May 1863.

For district nursing purposes, the city was divided into 18 ‘districts’, each made up of a group of parishes. Each district was under the charge of a Lady Superintendent drawn from a wealthy family. The system was non‐sectarian, though local ministers were encouraged to become involved. Liverpool was not alone in experiencing poverty and ill health and district nursing associations soon spread to other industrial cities – Manchester in 1864, Derby in 1865, Leicester in 1867, and London in 1868. The Victorian district nursing movement was characterised by several long running debates, which had their roots in views about social class and the role of working women. It took time, experimentation and organisation for the training of district nurses to become established. This coincided with an era of great advances in medical science and new ideas about the emancipation of women into paid occupations ( Figures 1.1and 1.2).

Читать дальше