Horace C. Grosvenor’s THE CHILD’S BOOK ON SLAVERY, OR, SLAVERY MADE PLAINappeared in 1857 under the auspices of The American Reform Tract and Book Society, a Cincinnati (Ohio) based abolitionist group that had been founded in 1852 by antislavery Congregationalists and Presbyterians, “to prevent slavery from possessing our new territories” (cit. Twaddell 130). The objectives of The American Reform Tract and Book Society can be read on the back cover of one of its pamphlets from 1856 ( Slavery and Infidelity, or, Slavery in the Church Ensures Infidelity in the World by Rev. William W. Patton). The text reads as follows: “The American Reform Tract and Book Society, it is believed, is the offspring of necessity, brought into existence to fill a vacuum left unoccupied by most other Publishing Boards and Institutions—its object being to publish such Tracts and Books as are necessary to awaken a decided, though healthful, agitation on the great questions of Freedom and Slavery.” This is its primary object, though its constitution covers the broad ground of “promulgating the doctrines of the Reformation, to point out the application of the principles of Christianity to every known sin, and to show the sufficiency and adaptation of those principles to remove all the evils of the world and bring on a form of society in accordance with the Gospel of Christ.”

Grosvenor’s volume is a noteworthy abolitionist text that provides a thorough description of American slavery and analyzes it from historical, religious and legal perspectives. The first chapter, “The design,” presents the content of the volume: “The design of this little book is to show the truth in regard to Slavery, and to give important information concerning it to all readers who do not already know it well. It is intended to show what slavery is, what the principles of truth and justice require us to think of it, and what the Bible teaches in regard to it. Be patient to read and think, and it is hoped that the book will do you good. It is addressed to children and youth; but, like most books of much profit to them, it is thought that it will be useful to many older readers.” In contrast to the most reputed abolitionist writings for children, Grosvenor’s text does not appeal to the emotions of its readers but aims to convince them through reasonable and objective data on the system. It asks them not to feel but to judge scientific information. The volume is divided into 28 sections: “The design,” “Have you seen slavery?” “The number of slaves,” “The duty of learning about slavery,” “Does color make slavery?” “What is a slave?” “Slaves can not own any thing,” “The difference between a slave and a child,” “A slave is not a hired servant,” “A slave is not like an apprentice,” “Slavery is not merely cruelty,” “The laws of slavery,” “The law is the mind of the people,” “Are there any kind slaveholders?” “A case of so-called kind slaveholding,” “Slave law treating a boy as property,” “A slave-father trying to get away from slave law,” “How slavery looks,” “Why slaves are not allowed to read,” “A little school for the slave children,” “Slavery laws against education,” “Ought any body to obey a wicked law,” “Have the masters a right to their slaves?” “Shall we make men slaves to make them good?” “Does the Old Testament uphold slavery?” “Does the New Testament uphold Slavery?” “A look at Slavery from the death-bed,” and “Can we cease to do evil and learn to do well?” Section 12, “The laws of slavery,” for example, provides specific information and quotes from the South Carolina code: “Slaves shall be deemed, held, taken, reputed, and adjudged, in law, to be chattel personal, in the hands of their owners and possessors, and their executor, administrators and assigns, to all intents, constructions, and purposes, whatever.” It also quotes from the civil code of Louisiana: “A slave is one who is in the power of a master, to whom he belongs; the master may sell him, dispose of his person, his industry, and his labor; he can do nothing, possess nothing, nor acquire anything, but what must belong to his master.” Section 21, “Slavery Laws against Education” presents examples of punishments in the code for teaching a slave to read. Information is also provided as to the punishments for a slave preaching. The texts are accompanied by small woodcuts that exemplify the information, and the frontispiece includes an image titled “View of the Slave-Pen, Washington City, D.C.” As Meg Elizabeth Gudgeirsson writes (152), an example of the many volumes produced by the American Reform Tract and Book Society out of Cincinnati, The Child’s Book on Slavery , was one of the books used by antislavery educational institutions such as the outstanding Berea College in Kentucky and in Sabbath schools. As a pedagogical tool for antislavery indoctrination, the text builds on what Benjamin Lamb-Books calls “the Republican frame” of the abolitionist discourse, since it presents “slavery as a social problem because it goes against values of equal rights and liberty from tyrants, the principles, enshrined in the nation’s collective memory of revolution and independence” (96). However, as with other books published by religious associations, it also emphasized the humanity of the slaves and their similarity to the young readers. Using these texts, teachers show how slavery was defended in different areas of American society and the many ways children could help advance the antislavery cause.

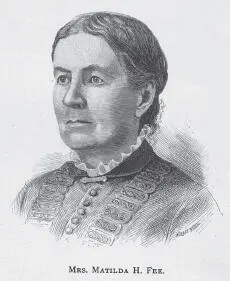

As the United States was running inexorably toward the outbreak of a civil war, the abolitionists kept on publishing texts for children in their attempt to prepare them for a potential conflict. As Jonathan Shectman (28) writes, in 1859 “abolitionism had fundamentally emerged from its accustomed place on the radical periphery to become a furious moral force in American public life.” “ SELLING BABIES” and “ A MOTHER IN PRISON” (1859) by Matilda Hamilton Fee are two brief texts included in the “Children’s Department of The American Missionary Magazine (1846-1934), a publication of the American Missionary Association, an abolitionist society that continued to dedicate itself to “the Negro Problem” until the appearance of the Civil Rights Movement. Matilda Hamilton Fee married Reverend John Gregg Fee in 1844, and both of them devoted their lives to the antislavery cause. Reverend Fee (1816-1901) founded the town of Berea in Kentucky in 1855 with help from the American Missionary Association and a local antislavery politician and wealthy landowner, Cassius M. Clay. In 1858-59 he founded Berea College, both of them going on to become sites of abolitionist activities. Fee envisioned the school as a model of educational racial integration in the middle of Southern pro-slavery territory. “What made Berea unique was its radical abolitionism located in the South” (Gudgeirsson 40). Yet, his illusions were soon shattered when in December of 1859 a mob attacked the college. The Fees left the town but returned in 1864, when the school unsuccessfully initiated the path towards integration. Among other things, Matilda collaborated with a column for children in The American Missionary Magazine . The second collaboration in April 1859 tells the story of the runaway slave Juliet Miles, who is separated from her children, to enlist the little readers’ “sympathies in the great cause of human freedom.” In 1858, as Gudgeirsson notes (204), Fee had written about the foundation of The Children’s and Young Peoples’ Anti-Slavery Missionary Association, an initiative of Berea College. The Fees explained that children also had a call to participate in the glorious work of destroying slavery, and that the object of the Association was “the promotion of a general interest among the young in missionary Associations, on Christian and antislavery principles, and more particularly for the support and extension of our missions in Slave States and their borders.”

Читать дальше