As the cover illustration makes clear, even if the fact that black persons born in American could be bought and sold, and separated from their families and “work without wages” is seen outside the home, the mother argues for the political commitment of those inside the house with the enslaved outside it. In Louisa’s “new home” there is no space for narcissistic self-contemplation. “You must try, my daughter, to forget your own sufferings in hearing about others,” says Louisa’s mother and urges her to take action: “When we know the truth we are better able to act, better able to decide what we ought to do. Now, if you think you can’t bear to hear and know about this slavery which is in your own country, you can turn away from it and try to forget it by amusing yourself and taking up other subjects that are not so painful. […] but we must act as well as feel; and as soon as you begin to do something you will bear better the knowledge of this painful truth.” Moreover, the mother encourages Louisa to perform an act of civil disobedience on behalf of the truthfulness of a higher law: “Yes, there are many good men and women who write against slavery, and some who devote much time and money to show the evils of slavery, and that it is opposed to that law which God has planted in the heart of every one to make him feel about it, as you do Louisa; and that when men for selfish purposes make such a law as forces Mary to leave us, that it is a wicked law, which must not be obeyed; and that you, and every body, whether man, woman, or child, should do all that is possible against it. A strong desire to do right shows a way to everybody, whether man or woman, boy or girl. So don’t think anything about whether you are a man or woman, but, whether you are to take sides with the right or the wrong, whatever it may be about.” The story turns out to be a radical statement against the passive acceptance of the Fugitive Slave Act and the active engagement of children in its demise. Louisa is guided by her mother to transform her intuitive empathy into a political force to protest against the system she naturally abhors. As with other abolitionist fictional mothers, Louisa’s is charged with the moral upbringing of her children so that they can step outside into the social world of nineteenth-century America and become critical thinkers and political agents.

In 1855 Harriet Newell Greene published RALPH; OR, I WISH HE WASN’T BLACK. Greene (1819-1881) was a writer, journalist and spiritualist who lived in Hopedale, Milford, Massachusetts, the utopian community founded in 1842 by Adin Ballou, a minister of the community of Practical Christians. Ballou, a pacifist, abolitionist, and defender of temperance, spiritualism and women’s rights, believed that his community could be an example of a socially reformed society. Yet, his utopian dreams did not come to full fruition and Hopedale only lasted about fourteen years before going bankrupt in 1856.

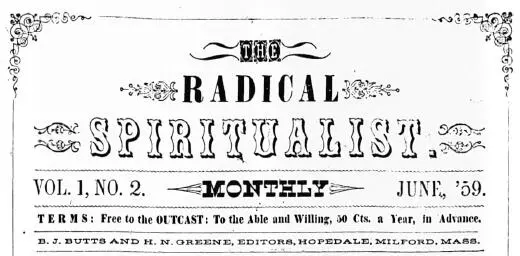

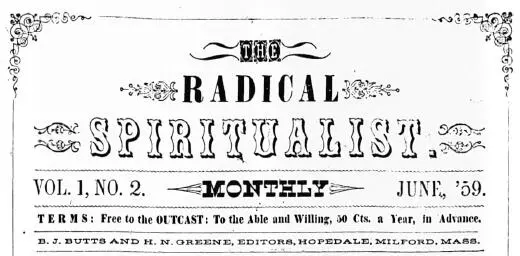

Harriet N. Greene, who had arrived in Hopedale in 1852, married Bryan J. Butts in 1858, a native New Yorker and a radical individualist, who joined Ballou’s community in 1852. Harriet would continue to write under her maiden name or under the pen-name of Lida. Both were reformists and members of Ballou’s utopian experiment, and in 1859 started to edit The Radical Spiritualist from May 1859 to October 1860. As utopian idealists, they wrote on a number of topics in the journal for the transformation of their society, including free love, abolition and the plight of fugitive slaves, temperance, spiritualism and women’s rights, among others.

The motto of the journal was “Free to the Outcast; To the Able and Willing, 50 cts. a year in Advance.” In the second issue in June 1859 it announced the editors’ intentions “to use language, on all subjects, which is direct and unequivocal, but to the purity and sincerity of which, every genuine reformer will spontaneously assent. As for others, whose fastidious tastes may be offended, we cannot afford to heed them. Our work is too important. We would have our ‘Voice’ heard in every corner of the globe, were it possible; yea, we would have it heard in the spirit realm, by the ‘spirits in prison.’ But we do not expect a ready hearing” (14). The journal presented itself as designed for a new class of readers that exceeded the categorizations of any spiritualistic publication: “the Outcast, the Degraded, the Prostitute, and the Enslaved.” In fact, the journal favored reformist writings on all subjects besides spiritualism, a theme that was given attention in such sections as “Notes on Spiritualism” and “Editor’s Portfolio,” together with reports of visiting mediums and other journals in the same field. In its first issue it also stated that “The world needs men of sterling worth, aye, and women too; great souls, who dare be true to the teachings of the inward voice—who are capable of feeling the pulsations of the great heart of suffering humanity, as it swells in awful surges like the restless waves upon the billowy ocean […] God is speaking in tones that cannot be mistaken—saying, ‘Labor fearless, labor faithful.’ And shall we, who have heard that voice, cowardly sit with folded hands, not daring to speak against the popular evils of the day? No! We will speak our convictions, whether the world smiles or frowns. We will call Slavery, Slavery; War, War; and Licentiousness, Licentiousness, whether it be hidden away in dark places, or stalks abroad at noonday, with brazen face, in Legislative hulls and Senate chambers” (1). The journal therefore included not only spiritualist themes but a vast range of reformist movements of the time: antislavery, temperance, socialism, women’s rights, vegetarianism, socialism, etc.

Greene was a feminist, deeply committed to universal reform, and wrote several children’s books on moral values and racial equality: Little Harry’s Wish, Or, Playing Soldier (1868); Little Angel, A Temperance Story for Children (1868), Little Susie; Or The New Year’s Gift (1873). In The Radical Spiritualist , together with her husband, she published antislavery texts with William Garrison’s radical abolitionist motto, “No Union with Slaveholders” in some of its issues. In August 1859, for example, she wrote a narrative titled “The Heroic Fugitive,” celebrating the bravery and humanity of a runaway woman slave in her community, and asking readers: “Who says that the slaves are satisfied with their condition? Who would be willing to change places with them? Would to heaven that those who apologize for this giant evil, were obliged to endure but for a single day, what the slave has endured for centuries. To every humane person, and to every Spiritualist especially, would we say, when this fugitive comes to your door, in the name of humanity, aid her by your words of kindness and deeds of love.” Her text was followed by Butts’s poem “The Angel and the Slaver.”

Ralph; or, I Wish He Wasn’t Black is an example of Greene’s commitment to the abolitionist agenda. As Linda Hixon explains, she must have been a participant of the Hopedale Sewing Circle, a group that mirrored the community confrontation with the system of slavery and, in contrast to many other sewing circles, was even “supportive of disunion to remove the country from the stain of slavery” (122). The cover of the story shows the figure of the kneeling slave with the traditional abolitionist religious caption of “Have we not all one Father?” The question is expanded at the end of the tale with a poem on the brotherhood of all persons. The narrative tells of two friends, a white boy called Ralph Medford and a black one called Tommy Willard, and expands on the absurdity of racial prejudices as well as the injustice of the Fugitive Slave Law, since Tommy’s father, a fugitive in the North, has been taken back to his owner in the South. As in previous abolitionist writings for children, mothers play a leading role in the moral indoctrination of their children. When Ralph feels threatened by the company of Tommy and his mother, Aunt Molly, in church, Mrs. Medford “felt that prejudice had already been sown in his young heart, and she knew how hard a thing it was to be rooted out, when it had once obtained root in the plastic soil of the soul.” Once more, the maternal influence is shown to be a decisive factor to educate children and impress upon their minds the divine legitimacy of interracial brotherhood. The author, however, takes advantage of Mrs. Willard’s concern as a domestic moral abolitionist to harangue against traditions and forms of Christian practice rooted in earlier Calvinistic theology that stood in contrast to those derived from the Second Great Awakening and the Evangelical revivals. Thus, Tommy “was not only taught book science, but was also taught goodness. His mother took every opportunity to impress upon his young and tender mind the truth and beauty of religion. Not that religion which clothes itself in gloom, and causes a sombre cloud to rest pall like, on the free, glad spirit. No, this was not the religion which Mrs. Medford possessed. Hers was a joyous piety, a piety which could see God in everything, in the little flower that bloomed so carelessly at her feet, in the song of birds in gentle, running brooks, in the starry heavens, all, all proclaimed to her the God of love. In the human soul, also, she saw the divine as well as the human; and no soul, however lost in guilt and folly, did she pass by. Her religion was a hopeful one, and she believed that God kindly cared for all, and would never forget a soul which He had formed. The dark Theology of the past with its blighting influence found no resting place in her benevolent soul; and while she saw God in everything that lived and moved, and dwelt with joy and sweet satisfaction upon all his beautiful works, she forgot not the meek and lowly Jesus. She felt that His life was a pattern, and she humbly tried to follow in his footsteps.” As an Evangelical Christian, Mrs. Medford’s maternal influence presses moral issues in the domestic space. She educates her son, a future citizen of the American republic, and instills in him concepts of human betterment and racial equality under God’s grace and love. As the narrator declares, “[t]hus did Mrs. Medford early impress on the plastic mind of her little boy, truths lofty and pure, simplified to his youthful comprehension.”

Читать дальше