Thomas published a long list of works, some of them addressed to juvenile readers. The Gospel of Slavery: A Primer of Freedom , published by W.T. Strong of New York, at a time when the Thirteenth Amendment had just been passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, and slavery and involuntary servitude had been abolished, differs radically from The Anti-Slavery Alphabet published in 1846. This primer is not addressed to little children, but to young adults with a far more thorough knowledge of American politics. Thomas accompanies each letter of the alphabet with a striking illustration, a fairly long poem, and an explanatory footnote. The Gospel of Slavery adds to the number of antislavery primers published during the prewar years. Each letter corresponds to a lesson and presents a key word related to the slavery system, which is illustrated by a graphic woodcut image and accompanied by a verse text that responds to arguments sustained by the defenders of the institution. Below the poetic description there are some lines of prose that offer a factual explanation of the argument exposed above and give further food for thought on those principles. The first lesson on the letter A, for example, points out the religious condemnation of slavery. Adam, as the unquestionable biblical father of humanity, highlights the equality of all people in the eyes of an all-seeing God. Savannah Teekel and Daniel Joiner explain that in this image “we see a representation of equality through the children’s differences. There is an all seeing eye of the Lord watching over them, or it may represent a symbol of knowledge which destroys the ignorance that enforces the evil of slavery. This eye is looking over two boys on a seesaw who are seemingly equal individuals in this picture. The noticeable differences in the images are in the boys’ skin colors and the buildings behind them, which may represent their class levels. The balanced position of the seesaw and the centered eye located vertically above the fulcrum of the toy portray equality of the boys with no regard to race or social class. In fact, because the all seeing eye is the all seeing eye of the Lord, and the illustration does not appear to acknowledge race and class, the reader is led to infer that the Lord doesn’t see race and class as important.” Thomas refers the reader to the Declaration of Independence and points out how inequality contradicts the founding principles of the nation. As with previous abolitionist writers for children, Thomas does not dodge the horrors of the peculiar institution and illustrates the letter B with the word “bloodhound” and its aggressive illustration of a dog attacking a runaway slave. All the letters in the alphabet are found to hide dark meanings for the enslaved. These possibilities break through the seemingly optimistic future of a Northern victory in the war and hold children to a past of injustice that belies the democratic principles of America as a nation of equality and fraternity.

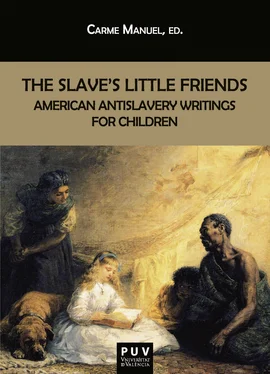

As in the illustrations appearing in The Slave’s Friend , the images in The Gospel of Slavery are “representative of literally thousands of other cuts and prints brought out in Boston and New York in the 1850s,” and they “almost universally present disempowered images of the slave” (Wood 97). Marcus Wood explains how these images were culled from the visual antislavery archive, representing what he calls “an iconography of passivity and dependency” (99). These images awaken the reader to feel “aggression towards the aggressor and sorrow for the suffering. The black slave is a figure to be protected, not admired” (Wood 97).

At a time of rejoicing over the barely won emancipation, Thomas confronted a reality of the recent past with ruthless honesty. Each letter was brought to represent the plight of the slaves socially, economically, sexually and politically. Moreover, he celebrated resistance of slaves—of both slave women and men—and their efforts to confront the injustices suffered at the hands of slaveholders, overseers, and common Americans.

The texts included in this anthology illustrate the wide range of possibilities that abolitionist writings offered to American children during the first half of the nineteenth century. Composing their works under the wings of the antislavery movement, authors responded to the unequal and controversial development of abolitionist politics during the decades that led up to the outbreak of the Civil War. These writers struggled to teach children “to feel right,” and attempted to instruct them to actively respond to the injustice of the slavery system as rendered visible by a harrowing visual archive of suffering bodies compiled by both English and American antislavery promoters. These writings for children went against the tenants of traditional nineteenth-century children’s literature but they also enclose many good religious and political reasons for being banned in contemporary times since they graphically illustrate the abominations of American slavery, and provide controversial visual evidence of a reality otherwise hidden and deemed obscene. Poetry and fiction bear witness to slavery’s wrongs and question the comfortable teachings of mainstream nineteenth-century education. Abolitionist authors of works for children turned slavery’s everyday realities into a dark replica of Victorian escapist fantastic and fairy tales. In contrast to the eagerness shown by nineteenth-century culture towards the protection and enshrining of children as innocent and angelic creatures, abolitionist writings shatter the crystal domes that kept them isolated from the world and made them face the bleak realities of their own country and actively share the righteous anger that dominated immediatist abolitionism (Lamb-Books 28). The gothic horrors of the Southern plantation world with its violations of the sacred institution of the family and the guilty compliance of Northern institutions are turned into a mirror for child readers to look into and judge whether they see themselves reflected in what they read. Antislavery authors were keen on raising their readers’ awareness of the adversities faced by African American children, women and men because they were convinced that reading abolitionist literature was a major way for the young to gain vicarious experience of the shattering hardships that enslaved Americans lived endured first-hand.

These texts present a wide range of controversial topics for the vast majority of nineteenth-century Americans. A short piece included in The Slave’s Friend (Vol. II, VII) warned against teachers’ fears of introducing the contentious subject of slavery into their classrooms and how these reservations also condemned them to a kind of moral bondage: “Many teachers are afraid to have anti-slavery matters discussed in their schools. They think that parents will take their children away if any thing is said or done on behalf of poor slaves. Thus this fear makes them slaves. White slaves!” The graphic depiction of ethically offensive behaviors, explicit portrayals of torture and compelling violent incidents in these texts vividly promoted dangerous and subversive ideas that went against the law and the Constitution of the United States. Furthermore, children were encouraged to react enthusiastically and to feel moral indignation, so as not to replicate the outrages and the corrupting power of slavery. Reading was equated with knowledge and knowledge was equated with moral responsibility, and therefore reading about “the abominations of slavery” became an act of emotional personal transformation. Abolitionist writings for children were provocative literature intended to raise their readers’ awareness about the political, economic, religious injustices that slavery enclosed; they repeatedly urged children to put themselves in the place of the enslaved Americans and sympathize with their plight. Children were thus turned into powerful agents of political change and potential activists to spread the abolitionist message. Invited to comply with a higher law that entailed the breaking of their nation’s edicts, children were morally rewarded by the Christian God and approvingly applauded by their elders for their violation of these same American regulations. These texts enclosed immeasurable value for young nineteenth-century Americans to fulfill a more democratic and egalitarian role in their future. Undoubtedly, abolitionist writings for children took away American children’s innocence and transformed them into juvenile abolitionists and empowered compassionate citizens.

Читать дальше