49 Wolfteich, Claire. “Animating Questions: Spirituality and Practical Theology.” International Journal of Practical Theology 13, no. 1 (2009): 121–143.

50 Wolfteich, Claire. “Time Poverty, Women’s Labor and Catholic Social Teaching: A Practical Theological Exploration.” Journal of Moral Theology 2, no. 2 (2013): 40–59.

Part I The Current Reality

Metaphors for Friendship:

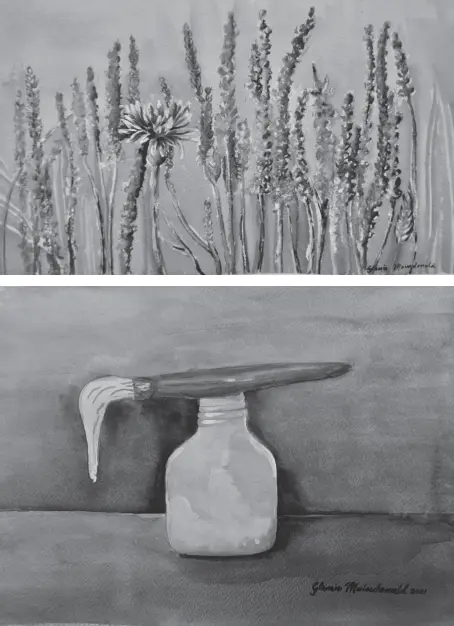

A Cornflower in the Wheatfield (I.1), Social Glue (I.2). Source : Glenis Maindonald.

1 The Place of Friendship

What is friendship, and what place does it have in contemporary communities? This chapter considers ways in which friendship is currently defined, understood, and lived out. Key interrelated themes include the question of whether friendship is essential or peripheral to what it means to be human; friendship’s place in our social world; the impact of technology on contemporary relationships and communities; the possibility of theological, ethical, or spiritual dimensions to friendship; and whether friendship is a private, public, or political relationship. Writings that have influenced the theological and social imagination of pastors and lay people over recent decades are included alongside broader Euro-Western cultural trends, and insights from anthropologist and sociologists. Whether regarded as an endangered relationship or an important source of social glue, friendship emerges as playing an invaluable role within contemporary communities, including communities of faith.

What is friendship, and what place does it have in contemporary communities? Practical theologians begin by articulating the way things are, before reflecting critically on contemporary experience in the light of theological norms. Thus, it is appropriate to consider how friendship is currently defined, understood, and lived out, and the norms, metaphors, and visions that underlie actions and practices.

The meanings and practices associated with friendship vary. Friendship, it has been said, has a place within a continuum of interpersonal relationships, from intimacy to enmity, with friendship, friendliness, indifference, and unfriendliness in-between. 1 Yet friendship can co-exist with intimacy and even, it seems, with enmity, given the existence of the term frenemies .

Friendship is an important yet under-researched relationship. Within various treatments of friendship several themes and questions arise. This chapter is structured around key interrelated themes including definitions of friendship, friendship’s relevance to what it means to be human, the place of friendship in our social world, the impact of technology on contemporary friendships and communities, theological, ethical, or spiritual dimensions to friendship, and whether friendship is a private, public, or political relationship.

Theological writings that have influenced the theological and social imagination of pastors and lay people over recent decades are included alongside broader cultural trends, works from the social sciences, and ethical, historical, and spiritual perspectives. This chapter focuses on the more recent past, while acknowledging that ancient understandings and ideals continue to influence contemporary understandings and ideals. Throughout the twentieth century, friendship has been variously regarded as a model for other relationships, disdained, valued from a primarily utilitarian perspective, and recognized as transformative. Controversy continues over the status of friendship in the early twenty-first century, and over the impact of new technologies on friendship.

I invite you, my readers, to consider the place of friendship in your own life and communities of practice. How would you define friendship? How has friendship been formative in your life, and contributed to the shaping of your identity and your life paths? Has friendship also been a source of pain, tension, or conflict? Is it messier and more lopsided than often portrayed? What impact have various forms of technology had on your friendships? Where have you experienced friendship contributing to community, and where has it detracted from community? What practices support the sustenance and growth of friendships? What questions do you have about friendship? The research presented in this chapter is primarily located within Western thought and culture, as is typical thus far for friendship studies. Are you immersed in non-Euro-Western understandings of friendship that may further challenge and enrich understandings and practices of friendship?

Friendship is used to describe a wide range of informal relationships, varying in levels of commitment and emotional attachment. The meanings attributed to friendship vary according to different historical and cultural contexts, making a consistent definition notoriously difficult to pin down. Nevertheless, friendships are consistently identified as chosen or voluntary relationships.

Current use of the word friendship in the Euro-Western world is challenged by a myriad of experiences and uses. Our lives and friendships tend to be segmented and compartmentalized: we may have leisure friends, business friends, and church friends. We can boast of how many friends we have on a social networking site yet have minimal contact with most of these people. Moreover, certain characteristics of friendship may vary through life stages. Childhood, teenage years, college, work, singleness, marriage, parenting, and retirement all provide diverse opportunities for and challenges to friendship. Currently many diverse interpersonal relationships go by the name of friendship, including easy friendships, not-so-easy friendships, increasingly difficult friendships, toxic friendships, aspirational friendships, ambivalent friendships, and unrequited friendship. Some would question the appropriateness of calling all these relationships friendship.

A variety of definitions of friendship have been proposed over the centuries. In antiquity, the Greek word philia , typically translated as friendship , included a range of relationships characterized by reciprocity in both willing and doing good for the other. Aristotle depicted philia as a symmetrical bond amongst equals, and philein as being characterized by reciprocity in wishing for another “what you believe to be good things, not for your own sake but for [the friend], and being inclined, so far as you can, to bring these things about” ( Rhetorica 1380b36–1381a2). Such relationships could include family and business associates ( Nicomachean Ethics 1156a7).

Subsequently, in the early Middle Ages, Isidore of Seville identified a friend ( amicus ) as a guardian of the spirit/soul ( animi custos ). 2 Commenting on this more open-ended definition, attributed to Gregory the Great, 540–604 ce, historian Brian McGuire identifies a sense of responsibility for another’s well-being, and knowledge of this person’s inner life, as elements implied by a custos animas relationship. 3 This sense of guardianship may or may not be reciprocal. Equality and mutuality are not essential, nor are they ruled out. Aelred of Rievaulx also focused on guardianship, alongside an emphasis on the ability to maintain confidences, exhibit patience and share all things. “A friend is called the guardian of love, or… the guardian of the soul itself” ( De spiritali amicitia 1.20).

More recently, sociologists Liz Spencer and Ray Pahl have identified a variety of types of friendship, ranging from simple friendship, including associates and fun friends, to complex friendships, including helpmates, comforters, confidants, and soulmates. 4 According to Charlie Brown, an icon of contemporary popular culture from the Peanuts comic strip created by Charles M. Schulz, a friend is someone who loves you despite your faults. A similar sentiment is expressed in the title of a mid-twentieth-century book for children: A Friend is Someone Who Likes You . 5

Читать дальше