A Companion to Arthur C. Danto

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Companion to Arthur C. Danto

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Companion to Arthur C. Danto: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Companion

A Companion to Arthur C. Danto

A Companion to Arthur C. Danto — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

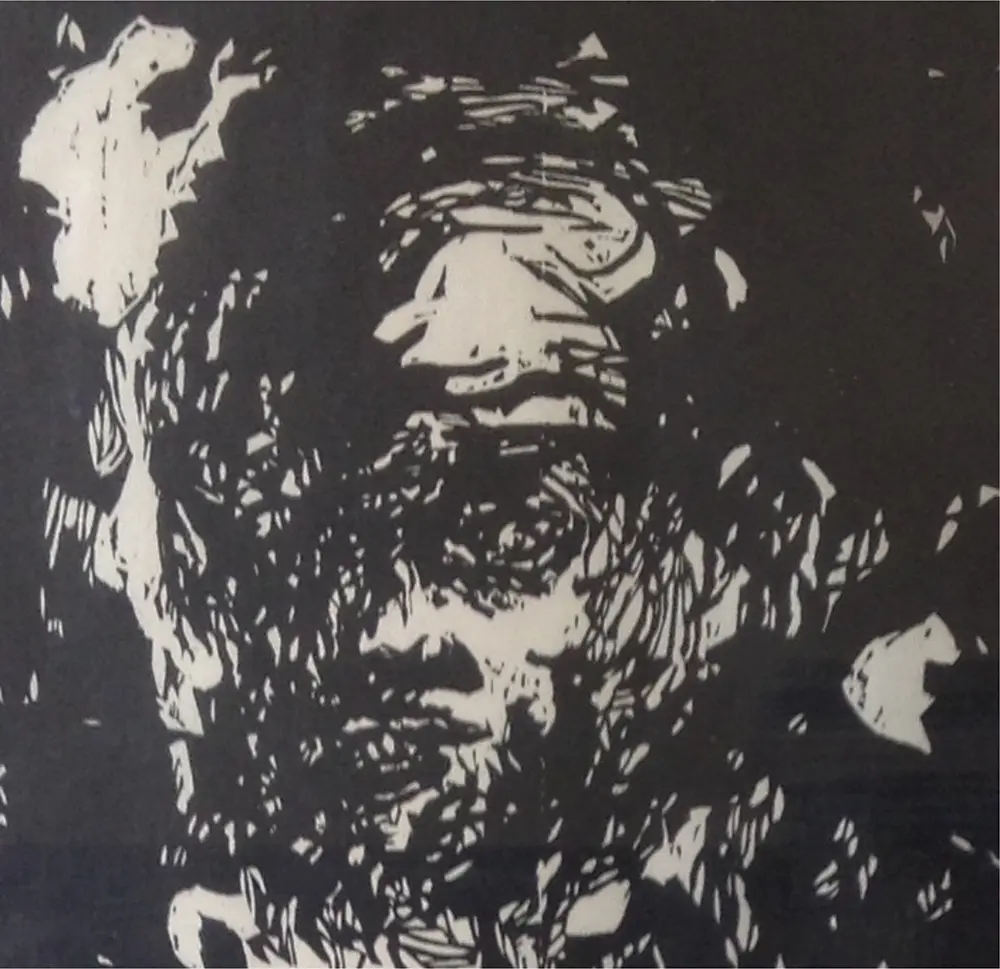

At Columbia, each year and for many years, I offered a year-long, graduate aesthetics course, a survey that was nicknamed “From Plato to Nato.” Nato was, of course, Danto, who generously agreed to come to the last class to present his work. The students sizzled with excitement when he appeared, even to the point where one very sweetly came up to me after class and said, “Oh Professor Goehr, it was so nice to meet a real philosopher face to face.” That Danto was the real thing was true; that he was the culmination of a long road that had begun with Plato was also true; he even, in his early life as a woodcut artist, produced an image that uncannily depicts Socrates as Arthur himself would later look. Artistic depiction always, he argued, transfigures. Even if I was a little miffed by not even being a candidate, in this student’s view, for entry into the philosophical-world, I blamed myself for offering a syllabus that rendered all the philosophers I taught almost indiscernible in appearance. So, as years passed by, I increasingly stressed the teaching to which Danto was most committed, that in the face of indiscernibility, don’t be taken in merely by what you see: work out wherein the differences between things lie. For then, things that look the same will no longer stubbornly be assumed to be the same sort of thing. And when we come to understand that, so many more ways of appearing will be granted entry into the hallowed halls, be they the halls of philosophy or of art.

In the last months, weeks, and days before Arthur’s death, I spent many hours in his company. Often we turned to opera as a medium for communication. I would take my IPad over to his apartment and play him arias from operas. He recalled having heard many of the great singers, but above all, he told me, he loved Amelita Galli Curci. On one of these occasions, Arthur began to sing, in perfect Italian, the opening love duet from La Bohème . The last piece he had read by me was an essay on this opera set into comparison with the red squares with which he had begun his book The Transfiguration of the Commonplace . Not able to hear very well anymore, he watched me listening to the aria and began to describe what he was seeing. He saw me not as listening but as singing to him. I did not know that this would be the last image he would ever have of me and me of him. Two days later, he received the first copies of a book for which he had been waiting a long time: the book that was his life and work, produced by the Library of Living Philosophers . A few hours later, he lost consciousness with the joy of knowing that he had left his world in good order and that he would meet again the friend with whom he had spoken every day for sixty years, Richard Kuhns. Not the belief but the image I have of Art and Dick now again taking a walk somewhere each morning in deep conversation is a comforting one in this time of mourning the loss of two friends who meant so much to me and so very much to each other.

Danto was born the year Puccini died. I had always wanted to write about them both together, which is what I have recently been doing and will continue to do. My book is not about endings and new beginnings, but about beginnings, first lines, which is where Arthur always was, given the excitement with which he woke each day to write. A year or so ago, he called me one morning when writing his last book, What Art Is , to tell me that he had suddenly understood something that he had never understood before: why Warhol with his Brillo Box was so central to him in allowing him as a philosopher to know what art essentially is. I did not dismiss his thought as repetitive; on the contrary, I thought back to how he had begun his Transfiguration with a red square that had been described by the philosopher who had so famously reversed the terms of repetition. Danto’s last thought about art had all the freshness of spring. He named the thought a wakeful dream. He had the ability to look at something so profoundly familiar – almost commonplace – as though he were looking at it for the very first time. His work now stands before us, asking always to be read anew, filled to the philosophical brim with the spirit of Art.

Figure 1Danto, “Socrates in a Trance” 1962 detail. Reproduced with permission of Lydia Goehr.

In Memoriam, Arthur Danto

Daniel Herwitz

Arthur Danto was born in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1924 and grew up in Detroit. He served in the military during the Second World War, driving trucks in North Africa and Italy. “I had a really great time,” he told me, making me wonder if anything at all could not, given his fascination with life, turn into an adventure. After the war, he studied Art History and Art at Wayne State then in Paris, becoming a printmaker of significance, a maker of images in the manner of German Expressionism, woodblocks with figures articulated in a chaotic swirl of lines, barely discernible in the intensity. At a certain moment in the 1960s, he took the decision to give up art, believing his work out of step with the Zeitgeist. This decision was made on philosophical grounds and without regret, for Arthur was already a philosopher dedicated to thinking through the conditions through which object, performance, and gesture may become art, spinning a theory as intricately inventive as any work of avant-garde art. He had taken the decision to continue at university and gotten a PhD at Columbia, and after a brief stint working in the philosophy of science turned to aesthetics. He was to spend most of the rest of his working life in the classrooms, galleries, and museums of New York, ending up Johnsonian Professor of Philosophy at Columbia while also serving as art critic for the Nation magazine.

It is well known that Arthur’s eureka moment on the road to Damascus took place at a West 58th Street gallery, the Stable Gallery, where he witnessed an exhibition of oversized Brillo boxes by Andy Warhol. Offered in play as a way of blurring the distinction between industrial and fine art, Arthur transformed Warhol into a philosopher in gel (one who wore his gel lightly). In Arthur’s view, Warhol’s boxes became revelations of the conditions that turn ordinary, real things into works of art. These conditions could not be anything visual since the box in the supermarket was (more or less) visually identical to the one in the gallery, but only the one was fine art. The man in dark glasses and a wig had hit on, with Arthur’s prompting, Leibniz’s problem of indiscernibility: that what makes two virtually identical things different in kind has to be something hidden and abstract. That something, Arthur argued in the Journal of Philosophy in 1964, could only be a background of shared theory: a set of concepts constructing terms for the box in the gallery to “make a statement” to the art world. Warhol could press the limits of the art world (with a supermarket box) and get away with it only because these concepts, at a moment of performance art, abstraction, and pop, were in place. Not that Warhol’s gesture was without controversy. Many took Warhol’s antics to be the attention-grabbing of a drugged-out denizen of the Velvet Underground whose pasty skin bespoke the need for a sunlamp if not a two-week vacation in Miami Beach. But the very fact of controversy proved (to Arthur) that the concepts were in place to allow for the argument.

It only remained for Arthur to articulate all the philosophy he believed implicit in Warhol’s gesture, and thus to complete a long history of avant-garde experimentation. On his reading of the avant-gardes they had always been in the project of self-discovery, which Warhol then brought to completion. Who needed to make expressionist woodcuts when the true thrust of art history had ended up in his lap?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.