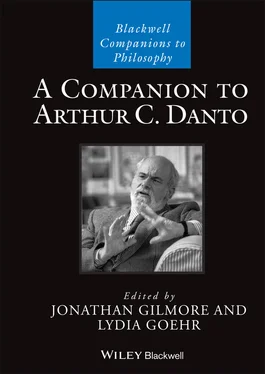

A Companion to Arthur C. Danto

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Companion to Arthur C. Danto

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Companion to Arthur C. Danto: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Companion

A Companion to Arthur C. Danto

A Companion to Arthur C. Danto — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Despite his insistence on the division of art and life and his consequent claim that art’s history evolves autonomously through “its own internal development” (Danto 1986, 204) rather than through external influences, Danto eventually seems to share pragmatism’s faith that art can make a significant difference to reality far beyond its effects in the artworld. In his book on Andy Warhol, he claims, “Revolutionary periods begin with testing artistic boundaries, and this testing then gets extended to social boundaries more central to life, until, by the end of that period, the whole of society has been transformed: think of Romanticism and the French Revolution, or of the Russian avant-garde in the years of 1905 to 1915 and of Aleksandr Rodchenko’s slogan ‘Art into life!’” (Danto 2010, 29). Many historians would argue, however, that the French Revolution is what inspired Romanticism, and that the Russian avant-garde were themselves very much influenced by social transformations that predated the 1917 Revolution. But the key point to retain here is Danto’s recognition of the strong links between art and life, even if he prefers to read the causality of these links only in one direction.

I conclude with a topic that, on the surface, sharply divides Danto from pragmatist aesthetics but at a deeper level unites them. This topic is “the aesthetic” and its traditional concern with pleasure and beauty. Danto has repeatedly insisted that the aesthetic is not central to the philosophy of art because most artworks are not made primarily for aesthetic purposes of beauty or pleasurable “delectation.” As “art is philosophically independent of aesthetics,” so he argues (citing Duchamp) that “delectation is the danger to be avoided” (Danto 2013, 144 & 145). Rather than beauty and pleasure, “embodied meanings” are what Danto regards as central to art; he even claims his definitional “theory, in brief, is that works of art are embodied meanings” (Danto 2013, 149). Danto essentially disregards the concept of aesthetic experience, focusing instead on interpretation as what is essential in art, not only for understanding an artwork but even for constituting it as such. Pragmatism, on the contrary, makes aesthetic experience central to our understanding of art’s meaning and value. Although recognizing that many (or, in contemporary practice, most) artworks do not make beauty and pleasure their highest concern, pragmatist aesthetics nonetheless affirms these qualities as having significantly shaped art’s concept and history while also contributing to art’s value. Pragmatism likewise insists that beauty and pleasure are often realized through the embodied meanings that Danto invokes as the essence of art. Danto assumes that the aesthetic deals only with the sensory surface. But the fact that aesthetics derives its name from sensory perception (and is concerned with such perception) does not entail that it is not equally concerned with meanings, for meanings can be sensuously rendered and directly perceived through our cultivated senses and sensibility, as when we directly see that a painting portrays the crucifixion with the established meanings that scene conveys.

Although Danto rejects the pragmatist view that aesthetic considerations are important for defining art, he ultimately converges with pragmatism’s affirmation of the aesthetic (including beauty) as having a deeper and wider significance for shaping life and thought more generally (Danto 2003). William James and Dewey argued that the fundamental unity and direction of our thinking and action are determined largely by the implicit aesthetic feel of things belonging together or flowing coherently in the right direction, in what James famously called the stream of consciousness. As James claimed in “The Sentiment of Rationality,” so Dewey argued in essays such as “Qualitative Thought” and “Affective Thought” that logical thinking rests ultimately on a felt sense of relevance and coherence (Shusterman 2011, 2013a, 49–68). Toward the end of the last chapter of his final book, What Art Is , Danto enlists neither James nor Dewey to make this sort of argument for the aesthetic, but instead invokes the writings of pragmatism’s originator, C.S. Peirce.

Peirce argued that aesthetics is, in a way, the most fundamental normative science, ultimately grounding the norms of logic and ethics: for if ethics subsumed logic’s concern with the good or right ways of thinking by being concerned with the nature of the good or right, then the ethical norms of good and right are in turn subsumed or explained by what is “admirable,” the nature of which is the subject of aesthetics, a science which Peirce sometimes described as “axiagastics” or the science of “the admirable” (Peirce 1967, 40, 1998, 201). In arguing that “ethics rests… on aesthetics” (Danto 2013, 152), Peirce further affirmed that a man’s ultimate ethical goal should be “to make his life beautiful, admirable” (Brent 1993, 49). We should not conclude, however, that for Peirce the quality of being admirable or aesthetically good is limited to beauty; instead it can be found in any distinctively unified “positive, simple, immediate quality” emerging from “a multitude of parts” (Peirce 1998, 201). This immediate quality has an affective feel or mood; and such a mood provides the implicit, hidden background that shapes what comes into the foreground of consciousness. Pragmatism, therefore, is essentially a philosophy of feeling as well as of action (Shusterman 2012, 433–54).

Associating these “aesthetic qualities” of feeling with Heidegger’s formative notion of “moods” that shape our thinking, Danto eventually even affirms their importance for understanding art, as he recognizes that artworks often “are intended to create moods, sometimes quite powerful moods” (Danto 2013, 153 & 154). This recognition of art’s role in producing powerful affect is precisely what motivates the pragmatist to make aesthetic experience a useful concept for understanding art, for illuminating its motivations, consequences, and value. Danto concludes, “What I admire in Peirce and Heidegger is that they have sought to liberate aesthetics from its traditional preoccupation with beauty, and beauty’s traditional limitation to calm detachment” (Danto 2013, 154). This is precisely the program of pragmatist aesthetics, whose pluralistic project also includes liberating aesthetics from its narrow focus on the definition of artworld art, enlarging its scope not only to the qualities and meanings of our natural and constructed environments and our wide-ranging products of design but also to the qualities and meanings of the ways we shape our lives.

Why did Danto not come closer to pragmatist aesthetics and its program of bringing art (and aesthetics) deeper and more pervasively into life by blurring the differences between them? Part of the reason may be a personal one of temperament in doing philosophy, as Danto himself suggests in one of our published exchanges. Discussing my comparative analysis of his “Upper West Side Buddhism” with the aesthetic experiences of my Zen training in Japan, Danto distances himself from what he calls “the existential spirit that informed and continues to inform [my] philosophical quest, as well as [my] life.” He immediately explains: “By this I mean a certain courage, an openness to risks of a kind I would never have exposed myself to” (Danto 2012, 308). Because I admire Danto as not only a brilliant but a courageous thinker, I would prefer to construe our difference here in terms of his overriding preference for experience as mediated and interpreted through art and philosophy in contrast to the greater openness and respect for the import of immediate experience (which is always already mediated by our cultural world and habits) that I share with classical pragmatism.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Companion to Arthur C. Danto» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.