The somewhat shameful fact is this: If you are looking at a corporate financial statement and actually trying to understand business investment, the number is nowhere reported. Our accounting profession has wrongfully determined that it is unimportant to keep track of what assets originally cost.

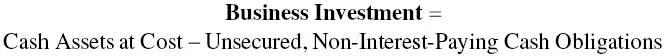

The next chapter will discuss the “right side” of the accounting balance sheet, which discloses liabilities and shareholder equity. But as a finance professional, some of the liabilities must be netted against cash assets at cost to arrive at business investment. Those liabilities are the ones having no cost and no claim on the assets of a business. Normally, there are two such liabilities: accounts payable and accruals. We have already briefly discussed the first of these, which represents trade vendors who are willing to give you clear title to their merchandise and then wait a period for payment. The second of these represents the timing gap between a service being provided and payment for that service. The most major example of this is employee wages; employees come to work and then generally must wait two weeks for their paycheck. There might be other unsecured, non-interest-paying cash obligations, such as customer deposits, which would be shown on the financial statement as a deferred income liability.

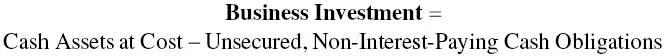

Variable #1: Business Investment

Number 1 of the Six Variables is business investment. To determine it, simply net accounts payable, accruals, and other unsecured, non-interest-paying cash obligations against the cash assets at cost. A short version of the business investment variable is shown below. Later on, I will expand this important variable to show its components.

While the accounting profession may have difficulty determining what business investment is, entrepreneurs generally can zero in on the number. One thing they know is that a lower business investment is better than a higher investment because it requires less funding. Certainly, the growth in global supply chain technology sophistication has played a role in the rise of “asset light” as a business term. If you can have less inventory, have extended trade credit terms, outsource your manufacturing, and then sell your product with fast payment terms, your required business investment can be substantially reduced. Had Daymond John been more “asset light” at the outset, his business investment requirement would have fallen materially, his liquidity would have substantially risen, and his risk of business failure reduced. As I learned a long time ago when I started out in banking, “Companies do not go out of business because they lose money. They go out of business because they run out of cash.”

1 1. J.D. Harrison, “When We Were Small: FUBU,” Washington Post, October 7, 2014.

Chapter 3 The Capital Stack and Two More Variables

Devising how to fund your business investment typically involves multiple capital sources. Those capital sources are mostly evident from the right side (or so it's always called) of the financial statement balance sheet, which is where liabilities and shareholder equity are reported. In finance vernacular, the various sources of capital used to finance business investment are often referred to as the “capital stack.” In the case of Daymond John, his capital stack was simple: He personally borrowed $120,000 on a second mortgage loan on his home and then infused that cash into his company as an equity investment. Typically, capital stacks are far more intricate.

I have found that most investors and entrepreneurs spend far more time focusing on the left side of the balance sheet than the right. In the case of STORE Capital, the most recent company where I served as founding chief executive officer, the left side of the balance sheet was loaded with profit-center real estate assets the company owned and leased on a long-term basis to service, retail, and manufacturing companies across the country. Most of the questions I fielded from investors and analysts stemmed from these investments.

When it comes to evaluating the right side of real estate company balance sheets, many corporate observers are simply inexperienced. For one thing, most public real estate companies have similar sorts of borrowing, with the resultant interpretation that the right side of a balance sheet is less important. However, this is far from so.

In 2005, at a predecessor public company, we conceived of a novel way to use serially issued secured debt. About three years after we embarked on this process, we sold the company to an investor group that was able to fully assume the highly flexible debt we had created. The result was that our shareholders were able to realize a compound annual rate of return approximating 19%, which would not have been possible without the flexible, assumable nature of our debt obligations. Had we simply followed the well-worn path of traditional financing options employed by most other industry participants, we and our shareholders would have missed out on this opportunity.

Borrowing sources can be instrumental in elevating shareholder rates of return, improving corporate flexibility, and even protecting shareholders in the event of severe economic turbulence.

Other People's Money (OPM)

When conceiving a corporate capital stack, there is an order of operations. At a high level, your analysis should begin with how much you can borrow, and then back into how much equity investment you might need . In the example of FUBU, Daymond John had no access to corporate borrowings when he founded the company. So, he made a $120,000 equity investment into FUBU that was funded by a personal loan he had to collateralize with his home. That small, but meaningful, investment ended up generating over $6 billion in revenues, ultimately making Daymond John an amazing financial success story. Over my years in business, I have seen similar success stories and have been proud to play a role in our customers' achievements.

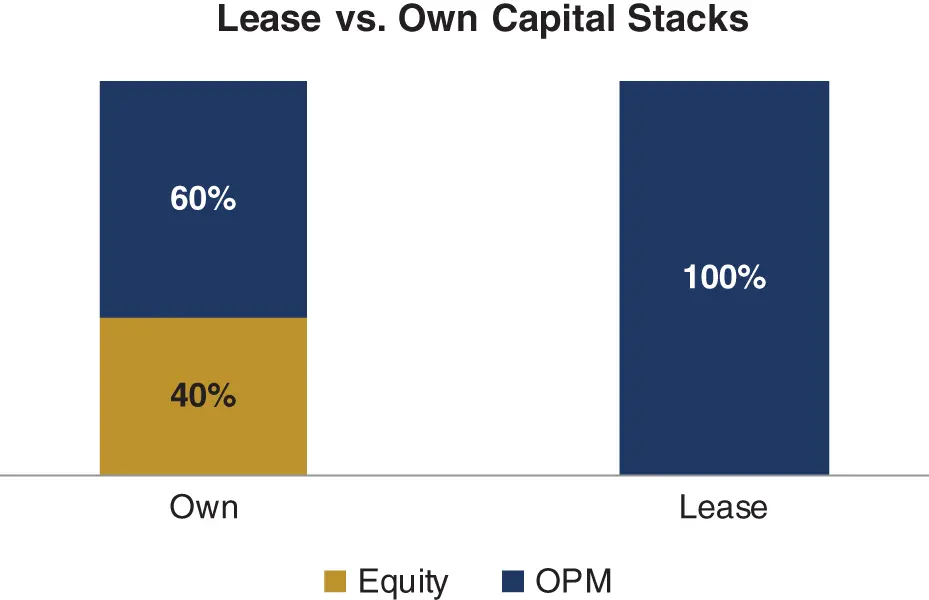

As a finance professional, I do not think personally about borrowings when considering how a business should be capitalized. That is too simplistic. Instead, I think about “other people's money” (OPM). For instance, STORE Capital is in the business of owning the profit-center real estate of companies and then leasing it to them on a long-term basis. There are numerous companies that use a lot of real estate in their business (think restaurants, fitness clubs, retailers, and many more) and they have a problem to solve. They could own the real estate and seek bank financing, or they could instead lease the real estate from a company like STORE.

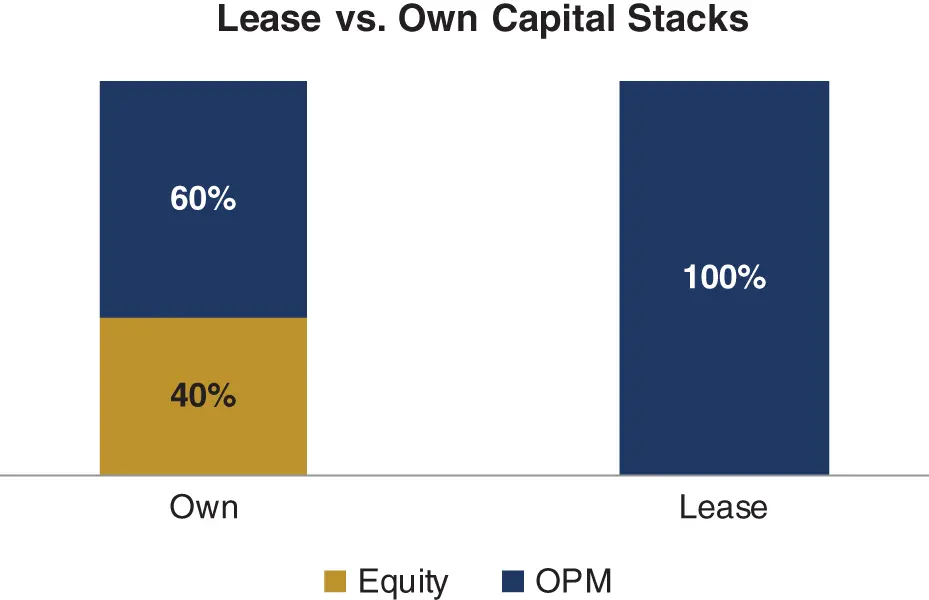

Real estate ownership requires an equity investment that can typically range as high as 40%, paired with borrowings for the remaining 60% plus. The alternative is to have a company like STORE put up all the money for the real estate, buy it, and then lease it back to you on a long-term lease. The amount of OPM entailed is different. A real estate lease offers far more OPM than does the choice of real estate ownership. Yet both are viable choices when it comes to creating a corporate capital stack.

As a self-described “finance guy,” I could care less about the accounting treatment of my capital stack. My attention tends to turn in the direction of equity returns, corporate flexibility, liquidity, and margins for error, which are important keys to value and wealth creation. I find that most corporate CEOs feel likewise. Hence, some will choose to own equipment or real estate, while others will elect to lease equipment and real estate. Either way, these decisions impact the corporate OPM and equity mix. They impact the capital stack.

Читать дальше