I was recently in Hong Kong and a friend there commented that China doesn’t have a history of civic engagement. Traditionally in China one had to accommodate two aspects of humanity—the emperor and his bureaucracy, and one’s own family. And even though that family might be fairly extended it doesn’t include neighbors or coworkers, so a lot of the world is left out. To hell with them. As long as the emperor or his ministers aren’t after me and my family is okay then all’s right with the world. I had been marveling at the rate of destruction of anything having to do with social pleasures and civic interaction in Hong Kong—funky markets, parks, waterfront promenades, bike lanes (of course)—I was amazed how anything designed for the common good is quickly bulldozed, privatized, or replaced by a condo or office tower. According to my friend civic life is just not part of the culture. So in this case at least, the city is an accurate and physical reflection of how that culture views itself. The city is a 3-D manifestation of the social, and personal—and I’m suggesting that, in turn, a city, its physical being, reinforces those ethics and re-creates them in successive generations and in those who have immigrated to the city. Cities self-perpetuate the mind-set that made them.

Maybe every city has a unique sensibility but we don’t have names for what they are or haven’t identified them all. We can’t pinpoint exactly what makes each city’s people unique yet. How long does one have to be a resident before one starts to behave and think like a local? And where does this psychological city start? Is there a spot on the map where attitudes change? And is the inverse true? Is there a place where New Yorkers suddenly become Long Islanders? Will there be freeway signs with a picture of Billy Joel that alert motorists “attention, entering New York state of mind”?

Does living in New York City foster a hard-as-nails, no-nonsense attitude? Is that how one would describe the New York state of mind? I’ve heard recently that Cariocas (residents of Rio) have a similar “okay, okay, get to the point” sensibility. Is that a legacy of the layers of historical happenstance that make up a particular city? Is that where it comes from? Is it a constantly morphing and slowly evolving worldview? Do the repercussions of local politics and the local laws foster how we view each other? Does it come from the socioeconomic-ethnic mix; are the proportions in the urban stew critical, like in a recipe? Does the evanescence of fame and glamour lie upon all of L.A. like whipped cream? Do the Latin and Asian populations that are fenced off from the celebrity playgrounds get mixed into this stew, resulting in a unique kind of social-psychological fusion? Does that, and the way the hazy light looks on skin, make certain kinds of work and leisure activities more appropriate there?

Maybe this is all a bit of a myth, a willful desire to give each place its own unique aura. But doesn’t any collective belief eventually become a kind of truth? If enough people act as if something is true, isn’t it indeed “true,” not objectively, but in the sense that it will determine how they will behave? The myth of unique urban character and unique sensibilities in different cities exists because we want it to exist.

City of Little Factories—the Old Crazy New York I

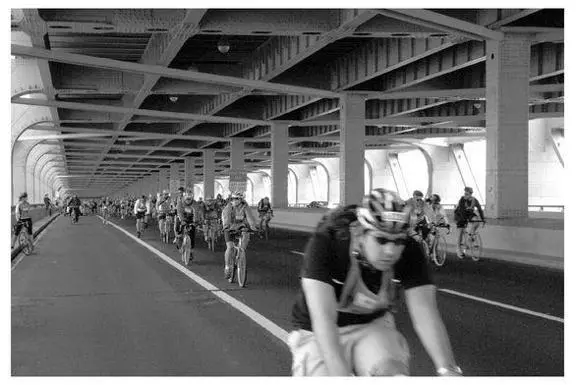

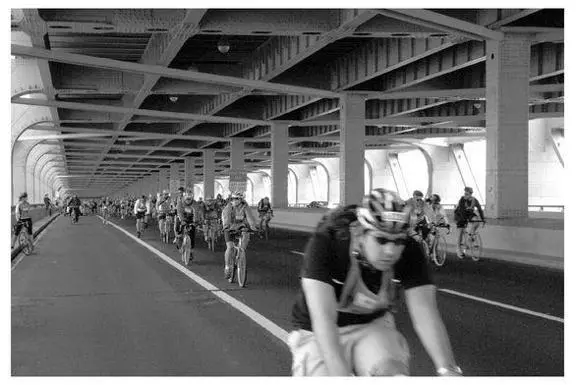

I ride in the Five Boro Bike Tour this morning. Forty-two miles! That sounds like a lot to some people but it only takes a little over three hours. And there are breaks. I thought I’d be more tired than I am, as I usually just ride locally to run errands or to get to work or go out at night. Corny as it might seem, it feels like I am participating in an uplifting civic event. People in Queens, Brooklyn, and Staten Island put signs in their yards and cheer the crowds of bikers as we whiz by, like they do for the runners in the marathon—only in this tour no one is racing. No one is keeping track of who comes in first.

The organizers have closed part of the FDR Drive, the BQE, the Belt Parkway, and the Verrazano Bridge—so we participants get the thrill of riding in the middle of a highway, and of not having to stop at red lights. Gone are the worries about the ubiquitous jaywalking New York City pedestrians hell-bent on suicide missions.

There are a couple of mandatory stops—for water, free bananas, and peanut-butter crackers—in Queens and near the Brooklyn side of the Verrazano Bridge, so racing and winding your way to the front of the pack get you nothing—except maybe the best bananas.

There is lots of spandex, way too much spandex. There is a characteristic sound of spandex skidding on asphalt that I’ve heard a couple of times already. I guess, for some, the fun of these events, or the fun in weekend cycling, is in dressing up. A change of outfit announces, “I’m doing this now! I’m a biker today.”

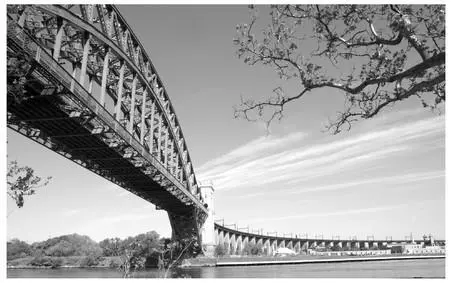

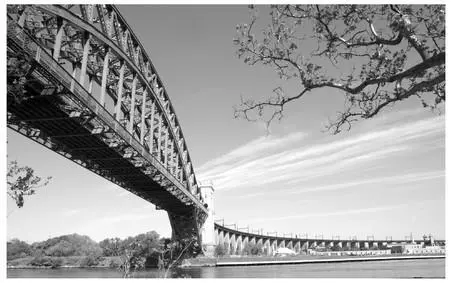

9:30 AM: The view toward Randall’s Island from under a railroad bridge.

12:00 noon: I’m riding over the Verrazano Bridge, which means I’m almost done. From here it’s a short ride to the Staten Island Ferry and back to Manhattan.

Of course, some guys (and gals) who join this event are a little behind on their bike manners, or maybe they are trying to prove how manly they are—both to themselves and to everyone else. There is some high-speed zooming and jockeying for those meaningless leads. I had been warned that the most dangerous aspect of this thing would be the other cyclists—especially those who are determined to get closer to the front of the mob—wherever that is. I can’t even see the front anymore. The compact clump at the starting area in Lower Manhattan quickly elongates by the time it leaves the island. (This is accomplished intentionally by creating a couple of bottlenecks on Sixth Avenue in midtown that causes the ridership to become less dense.) It’s not just the hotdoggers that you have to watch out for. The fact that there are so many cyclists here who are not used to riding and certainly not used to riding en masse, scrunched together, inevitably leads to some absentminded behavior that can cause some nasty pileups.

Mostly though, there is a rare and great feeling of civic togetherness—something we New Yorkers regard as suspect, but that’s what it is. We have to give in to it—the feeling generated when a mass of people do something together, energetically, en masse. Like what happens in a mosh pit or on a roller coaster—a deep biological thrill gets triggered. Unlike some crowds this is a friendly mob, happy to abide by the barriers and traffic cones (for the most part), running on banana and peanut butter crackers power.

The longest part of the route goes through the waterfront neighborhoods of Brooklyn and Queens, which gives one the pleasantly skewed impression that the old, nutty industrial city that New York once was still exists. These neighborhoods are made up of an endless series of little factories that make plastic wrap, cardboard boxes, ex-lax, coat hangers, hairbrushes, and the wooden water tanks on top of every Manhattan residential building. Sure, some neighborhoods like Williamsburg, which we riders touched the edge of, have filled up with art galleries, cafés, and wonderful bookshops, while other neighborhoods are all Hasidic or Italian, but mostly the waterfront area is still composed of funky factories. These old structures are a million miles from the industrial parks, high-tech campuses, and corporate headquarters that one sees out west (west being across the Hudson). They are small in scale, and often they are family run. These are the places that make those glue-on reinforcement rings for notebook pages and apple corers that you look at and think, Who thought of that? Who designed that? Someone actually thought that up?

Читать дальше