I’m not sure I know anyone, anyone at all, who is completely sane. Sure, I know plenty of people who play the sanity game with skill and daring. Their masks of having it together are well secured, and they don’t spit out profanities or stare googly-eyed into space. Above all they have learned to function well enough socially to be accepted as “normal.” My friends are not an exclusively eccentric arty crowd either—most are what would be referred to as normal.

The poor outsiders never learned or mastered those social skills. Even a would-be self-marketer like the Reverend Howard Finster of Somerville, Georgia, never quite got that part right. Either his preaching and ranting got in the way—fire and brimstone don’t mix well with white wine and cheese—or he didn’t realize that in the art world, one simply can’t be seen as blatantly hawking one’s wares, which Howard didn’t mind doing because he saw his work as serving a greater glory. He was proselytizing; he wasn’t really pushing “himself.”

There’s an elaborate song and dance involved in passing for a professional artist. One needs to veil the sales pitch, for starters, and that protocol, those dance steps, must be mastered, as is true in any profession. But one can be mad and self-obsessed, can believe in other worlds and the influence of supernatural forces, and still be regarded as a respected, “sane” artist—no problem.

Sophisticated artists who can draw well—Klee, Basquiat, Twombly, Dubuffet—often intentionally draw in a more “primitive” manner. They are seen, partly due to the rough nature of their mark making, as tapping into something deep and profound. The crude lines imply that one is in touch with unconscious forces that won’t submit to the urgings and smoothing tendencies of craft and skill. It’s not an unreasonable or completely untrue idea, either; funky drawing does push some elemental buttons, and maybe the work of these artists does come from a deep and profound place that won’t submit to polishing. I’m not saying they’re fakers. I’m simply noting what their kind of gestures connote.

The generally accepted idea is that if it’s rough, it must be more real, more authentic. Yet the poor outsiders, whose marks are very often every bit as unpolished, can’t help how they draw—they couldn’t make a clean line if they had to. So they are left out of the art “club.” They are doing the very best they can but because their lack of exhibited drafting skill is, we believe, not their choice, they are often viewed as lesser artists. They can’t help drawing crazy shit, while the sophisticated artists could, at least so we imagine, draw a nice puppy if they had to. It would seem to be all about intention. And yet, these outsider artists most certainly have intention. They know when a line is right or when it’s “untrue” according to their personal standards. They have definite intentions to achieve a very specific visual look and effect—at least one would assume so given that they often labor mightily to re-create that look again and again.

This aesthetic segregation seems perverse. I enjoy much of the work of the four very successful professional artists mentioned above, but probably what moves me is when their work touches something deep that we all have in common. It is the same something that the outsiders sometimes tickle and activate in the very same way—proof that these charged marks and images can resonate with nearly anyone. They touch those same deep, dark parts of themselves and ourselves. The difference is the poor loonies can’t remove themselves from the experience of communicating with extremes of dark or light and step back and away from it. To distance oneself, to feign objectivity, this, then, is the mark of a “civilized” person. It’s a useful, possibly essential, social skill to have, but it’s not, in my opinion, a criterion by which to judge creative work.

The great works of antiquity, the classics, could have been made by nameless (to us) skilled obsessive nutters—many of their personal stories are certainly lost to history. So maybe they could have been complete misfits too—but who cares?

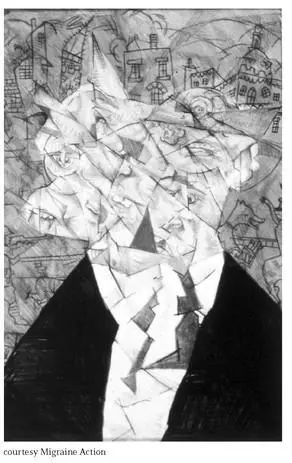

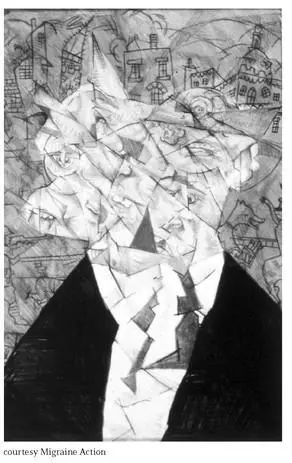

On the next page is a painting made by a migraine sufferer. It depicts—so we are told—not a metaphorical interpretation of the headache but a realistic depiction of what the sufferer sees when the migraine strikes.

It makes one wonder if Braque and other cubists suffered from migraines and were painting what they actually saw. Would that make a difference? Would we think less of them as artists if that were the case?

The crossover between inside and out is not just confined to the visual arts. Beckett, Joyce, and Gertrude Stein produced obsessive and inscrutable works—but they managed to function and even won prizes for work that many still call mad. Whether something is made by a sophisticate or by a person who is functionally challenged, in recent decades it often comes out the same. And, as time passes, traditional skill and craft become less desirable qualities, and expression, truth, and emotion are deemed more important. Artists and writers are encouraged to dive into their inner depths, so it shouldn’t be surprising at all if some of the same strange fish are caught. The creatures from the deep can be pretty disturbing and wacky, but we all recognize some part of ourselves in them, no matter who dragged them up.

As my friend C points out, it’s fairly common for someone to attempt to denigrate someone else’s creative work by claiming, “They’re not a nice person.” It’s as if the fact that someone has a lousy personality, is a bad father, engages in phone sex, or is obsessed with little boys or little girls implies that their work is therefore less good. Does it? Surely no one cares if an artist is merely a little stingy or is gay or not anymore. Most people would say that those bits of information are often irrelevant and have no bearing on whether they like the work or not, or whether it should be taken seriously or not.

But doesn’t the fact that Ezra Pound made radio broadcasts in support of the Fascists or that Neil Young was a Ronald Reagan supporter or that some composers and artists apologized for Stalin—or even for Hitler—make their work suspect, even worthless in some cases for many of us? At what point does the extra-creative activity of the person begin to make a difference in how we perceive their work? This question presumes that those political sympathies or sexual perversions actually show up in the work—and I’m not even talking about work that is blatantly propagandistic. If we opt to denigrate Speer’s monumental architecture then there are a whole lot of other architects who, judging by the way their work looks, are equally “Fascist,” and many of them are working today.

Where does one draw the line? Should we only judge by what is in front of us?

A History of PowerPoint

I do a talk about the computer presentation program PowerPoint at the University of California in Berkeley for an audience of IT legends and academics. I have, over a couple of years, made little “films” in this program normally used by businesspeople or academics for slide shows and presentations. In my pieces I made the graphic arrows and the corny backgrounds dissolve and change without anyone having to click on the next slide. These content-less “presentations” run by themselves. I also attached music files—sound tracks—so the pieces are like little abstract art films that play off the familiar (to some people) style of this program. I removed, or rather never included, what is usually considered “content,” and what is left is the medium that delivers that content. In a situation like this one here in Berkeley one is usually asked to talk about one’s work, but rather than do that I have decided to tell the history of the computer program itself. I tell who invented it and who refined it and I offer some subjective views on the program—my own and those of its critics and supporters.

Читать дальше