Of course, I didn’t exactly want to suffer those kind of travails, but what struck me was that the bike provided a conduit for stories, unusual stories, stories that you weren’t likely to get as a backpacker where you’re subjected to the tyranny of bus and train schedules, tourist touts, that inevitably lead to a sameness of experience.

I had, however, had the brief joy of cycle touring with Al through New Zealand. We were unfit, flabby and so under-prepared and swore never to travel with each other again (actually, I think we just swore). But what we both liked was that you got time to enjoy the environment more, smell it, feel it, unlike the countless Maui Campervans and tourist buses that rushed from town to hotel, hotel to town.

Dervla’s stories set my imagination in motion. The question was: where to go?

Of late I had been under the spell from travellers’ stories of the Sub-Indian continent and India soon seduced me with promises of exotic desert nights, ancient architecture, colourful tribes, renegade hippies, yoga and Bollywood movies. I wanted to taste her spices, feel her dust and her rain.

As for China, I heard things were changing quickly there. Foreigners no longer had to take a guide with them, and more of the country was becoming accessible. With a bike, the possibilities of unrestricted travel (except in Tibet) made China just that bit more enticing. The more I thought about it, the more I really liked the idea of being lost in a foreign culture: I wanted to be confused by Chinese street signs, eat things that questioned my better judgement, and be that weigoren stumbling through backstreet markets lost to it all as the soft lilts of Mandarin swirled around me.

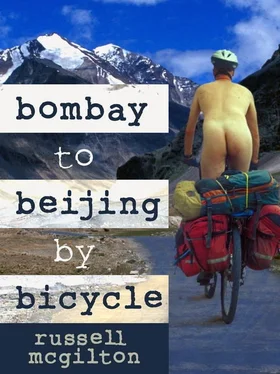

So late one night, flipping through an old high school atlas and admiring the well-rounded contours of the Himalayas flowing into India and China, an idea hit me: if Dervla cycled from Dunkirk to Delhi, then why not… Bombay to Beijing?

I set out a pile of matchsticks like a trail of ants across the atlas and came up with an exact distance of…

Well, approximately 10 000 kilometres. If I cycled 55 kilometres each day, I would be able to complete the trip in eight months (with tea breaks, maybe ten). It would be a doddle!

‘Bombay to Beijing by Bicycle… what a great title for a book!’

Except there was one big problem with that.

1

MELBOURNE – BOMBAY/MUMBAI

January, 2001

I have never liked flying, and I was about to never like it even more. At 35 000 feet, this became abundantly obvious.

‘You are cycling from Bombay to Beijing?’ asked a rotund Indian man sitting next to me while Denzel Washington flashed across a small television screen above us in football gear. His name was Deejay and though his name might suggest something in the hip music world, he was in fact an IT consultant living in Sydney.

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘But why? We have trains and buses there. Much easier for you, I think.’

‘Well, you see, cycling lets you delve into the lives of people you wouldn’t normally meet. You get to be one with the landscape, letting it wash over you.’

He snorted. ‘To be with the common man?’

‘Well, that’s part of it. I’m writing a book and I thought Bombay to Beijing by Bicycle would be an excellent title.’

‘Ah, the alliteration.’

‘Precisely. The bum-de-bum, bum-de-bum sound,’ I said, thumping my hand on each ‘b’ to stress the point.

‘Bombay to Beijing by Bicycle!’ He laughed, then sipped his tea thoughtfully. ‘Only…’

‘What is it?’

‘Bombay, my friend, is not Bombay anymore.’

‘What?’

‘This is the old name. It is now Mumbai.’

I gulped my scotch, spilling it down my chin. ‘Oh, sure. Right. I know. It’s just that in my guidebook it’s got “Mumbai slash Bombay”. I mean, doesn’t everyone still refer to it as Bombay? You know, when I was in Ho Chi Minh City the locals kept calling it Saigon. Or Myanmar still being referred to as Burma. You know, one and the same… interchangeable… well, aren’t they?’

‘No, no. It is Mumbai.’ He grinned then put on his headphones and went back to watching Denzel teach white boys how to tackle.

‘Mumbai…’ I said to myself. ‘Mumbai to Beijing by…’ I looked out at the escaping Australian desert, suddenly wanting to retrieve it.

‘Shit!’

* * *

The next morning I woke to the sound of the phone ringing.

‘Good morning, sir. Breakfast? Budda toast, omelette, chai . Vhot are you vanting?’

‘Could I please have the buttered toast, chai , omelette… jam?’

‘Okay.’

He hung up.

I opened the drapes. The sun was out, warming the run-down and mildewed buildings opposite, their window ledges chalked with pigeon shit. Dusty rainwater pipes ran this way and that like some alien mechanical creeper while a large yellow sheet, hung out to dry, tongued its way down a wall.

This was the daylight squalor I had imagined as I bounced around Mumbai’s traffic the previous night.

‘Sorry, sir,’ the taxi driver had said, swerving out of the way of a doorless bus. ‘Much traffic bumping. No good here in India. Many bad peoples driving without permission.’

I was in Colaba, a narrow peninsula of Mumbai bubbling with hotels, tourists, markets and restaurants by the sea. Under the morning sun, ragged men, dark as the rubbish around them, shovelled clumps of brown muck onto wagons pulled by water buffalo while business men briskly marched past, skipping over holes in the pavement as their leather briefcases pumped them towards towering office buildings. Women delicately tiptoed around a beggar sitting by a gift store, their gold and red saris floating around the women as if they were walking under water. Meanwhile, inside my hotel, a child exhausted itself into convulsive, tearful retches.

Mumbai sounded big, and with good reason. Over 16 million people live, [iv] vi This figure is now over 20 million

work and breathe in this colliding metropolis. It has the biggest film industry in the world, more millionaires than New York, and a port that handles half of India’s foreign trade. Workers from Assam, Tamil Nadu, Rajasthan and even as far away as Nepal come here to make it big in this collective maelstrom, doing any work they can find. Many are unlucky and find themselves in one of the largest street slums of India, if not the world.

I turned on the air-conditioner and looked at the mess that had taken over my room: a Trek mountain bike: four panniers (bike bags), a handlebar bag and a medium-sized backpack. A total weight (bike included) of 43 kilograms. [v] See the back of this book for a detailed list

While Dervla Murphy carried only a small kitbag of clothes, a handgun and a dash of courage, I felt it prudent to pack for the worst.

Just as I was considering all this the door burst open.

A porter, sweating in the humidity, charged in with breakfast, and put it on the table. This would be a common experience for me in India – staff walking in on me without a knock catching me in all sorts of undress not to mention compromising situations.

‘Welcome to Bombay, sir.’

‘Bombay? I thought it was called Mumbai?’

He smiled. ‘As you like.’

Deejay had been wrong, it seemed (or just winding me up). As I would find out later, Indians were still using the name Bombay quite liberally: taxi drivers asked where in Bombay I wanted to go to, students eagerly asked for my impressions of Bombay, restaurant owners praised Bombay epicure, hotel managers requested information on the duration of my stay in Bombay, and the local film industry was still referred to as Bollywood, not Mollywood.

Читать дальше