One carne, dimly, to understand that the soil is a reservoir of moisture and that even in dry years the reservoir can be tapped by the farmer who is in on the scientific secret. The doctrinal heart of Campbell’s teaching lay in his near-mystical faith in the power of capillary attraction. If a very slender glass pipe is placed upright in a bowl of water, the water in the tube will defy gravity by rising noticeably above the level of the water in the bowl. So the Montana farmer had to coax the water on his land to defy gravity and rise to nourish the roots of his winter wheat.

Campbell diverted his urban readers with kitchen-table experiments that could be performed miles from the nearest farm. One was invited to suspend two plant cuttings in neighboring glass tumblers of water, and to float a thin film of olive oil on the water of the second tumbler, to deny air to the severed stalk. Cutting No. 1 would sprout healthy roots, while Cutting No. 2 would become a rotting stump. There were more experiments in tumblers with different sizes of buckshot (not so easily obtainable by the average apartment dweller), to demonstrate that small soil particles attract more water than large ones. In the novitiate period, at least, dry farming with Campbell was enjoyably like 101 Things To Make & Do . Here was science made plain for Everyman, and even as you sat at home in the smoke and din of the city, you knew that you were stealing a march on the mass of farmers, toiling in their fog of ignorant tradition.

When you eventually graduated from the kitchen to the land, you’d need to buy a Campbell Sub-Surface Packer to compact the soil at the root level of your crops. You’d also need a disc harrow to break up the topmost layer into a fine, loose mulch. The pulverized surface soil would collect the rain; the packed soil would store the moisture for future use. Campbell quoted a ripe testimonial given to him by Mr. J. B. Beal, Chief Land Examiner of the Union Pacific Railroad: “We find by the Campbell System that we can as well keep moisture in the ground as to put it in a jug and put in the cork.”

Anyone would be excited by Campbell’s figures. On his own farm, he had reaped 54 bushels of wheat to the acre. Using the Campbell method, Mr. L. L. Mulligan had gotten 75 bushels of barley; Colonel W. S. Pershing, 300 bushels of turnips; Joseph Emmal, 120 bushels of potatoes; and on the grounds of the State Soldiers’ Home at Lisbon, North Dakota, had been raised 23 tons of sugar beets per acre. With crops like these, grown on land once named a desert, Campbell’s drumrolling on behalf of his own system did not seem immodest.

The soil culture empire has no limits. The system is useful on every farm. It reaches over oceans and mountains. Over vast areas the principles are triumphing over the perverseness of nature. And some day this soil culture empire will be the garden spot of the earth.

In its rousing generalities, the Manual sounded like a political manifesto — as, in a sense, it was. Campbell was a disciple of both Thomas Jefferson and the current president, Theodore Roosevelt, and his book was shot through and through with Jeffersonian and Rooseveltian ideas. In the nineteenth century, American agriculture had been notoriously wasteful, its crop yields per acre far lower than those of Britain and Germany. Campbell’s system was intensive and — in one of Roosevelt’s favorite words — conservationist. It cherished the available natural resources of soil and water, and accepted the finitude of those resources in a way that Americans, with their careless habit of striking camp and moving on, had never really done before. It brought to farming a strict, Presbyterian ethic of saving, husbanding and staying home on your own plot.

Intensive farming meant small farms, Campbell had strong words for the big landowners: they squandered their acres and made little contribution to rural society.

Land greed has been the curse of farming. The farmer can no more do his best while trying to cultivate a thousand acres than by confining himself to a two-acre plot. He must have enough, but not too much.

So the 320-acre homestead was a farm of exactly the right size, and the homesteader exactly the right kind of citizen.

The small farmer is the one who makes his farm his home. He seeks comfort for himself and his children. He does not build a shed to shelter him during the crop season with his family miles away. He becomes a permanent fixture in his county. He wants the school house to be located not far away and he willingly taxes himself for the support of the school. He contributes to the erection of a church in the village and he is careful that the rural route and the cooperative telephone do not pass him by.

“The small landholders are the most precious part of a state,” wrote Jefferson in a letter to James Madison in 1785. And again (in a letter of the same year to John Jay):

We have now lands enough to employ an infinite number of people in their cultivation. Cultivators of the earth are the most valuable citizens. They are the most vigorous, the most independent, the most virtuous, and they are tied to their country, and wedded to its liberty and interests, by the most lasting bonds.

Jefferson’s vision of democratic America as a giant quilt of small farms was closely, perhaps slavishly, echoed in Campbell’s Manual . The tabletop physics, the patent Sub-Surface Packer and all the rest of the impedimenta of scientific soil culture were there to bring about a revitalized agrarian democracy.

The idea of turning the West into a garden and a cradle of superior civilization wasn’t new, but Campbell’s book made it seem so. It was up to date in its romance with the new century and its guileless optimism about science and technology. Campbell, born in Vermont in 1850, had come to adolescence during the Civil War. By the early 1900s he was able to look out on the America which his grandchildren were set to inherit, and see it as a land of spotless promise once again. It was fitting that the war veterans of Lisbon, North Dakota, were now producing phenomenal crops of sugar beets using the Campbell System; one sign among many of the wonderful new times ahead.

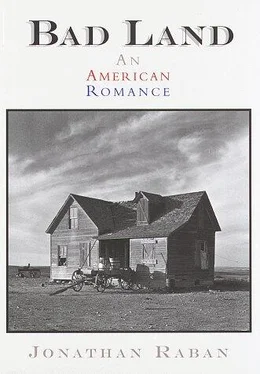

Mold and damp have had their way with my copy of the Manual , which gives off a thin, sour stink from its place on the desk beside the typewriter. Its spine was broken between pages 240 and 241, when someone trod on it with a muddy boot. The imprint of the boot (a size 12, I’d guess) looks like a deliberate verdict.

When Campbell wrote of how his system could enable readers to live “the ideal simple life,” I think he was making a direct allusion to another inspirational work. Charles Wagner’s The Simple Life was published in 1901 (in translation from the original French) and was an immediate and spectacular bestseller. The success of Wagner’s book (it sold more than a million copies in its Doubleday hardbound edition) is a gauge of the powerful tide of rural nostalgia that was washing through the industrial cities of Europe and America at the turn of the century. There was a deep and troubled hankering for a life more neighborly, more elemental, more “organic”; and the railroad pamphlets, Campbell’s Manual (along with several other books on farming for beginners) and the Enlarged Homestead Act found a receptive audience of people who were recklessly eager to believe in the idea of escaping the city to a new life in the country.

On the bestseller lists between 1901 and 1910, two sorts of generic fiction stand out — and they represent the masculine and feminine sides of rural nostalgia. The masculine ones romanticize life in the wild, on the frontier or the open range. The feminine ones, set east of the Mississippi, romanticize life on the farm and in the village. But, as in life, the genders get interestingly mixed up.

Читать дальше