Ismay — of course — stuck firm, and so did Mildred. The capricious way in which the company attached names to the land, then withdrew and replaced them, is a nice illustration of how the West was still thought of as a great blank page on which almost anything might yet be inscribed. Its history could be erased, its future redrafted, on the strength of a bad breakfast or a passing fancy.

The half-built new towns, in which the typical business was a shed with a two-story trompe l’oeil façade tocked onto its front end, were architectural fictions, more appearance than reality; and their creators, the railroad magnates, speculatively doodling a society into existence, were like novelists. The only serious check to the imagination of the railroad-and-city builder on the Great Plains was the problem of gradient. If a town already on the map offended him, he could starve it to death by bending the line of his railroad away from it (as James J. Hill, president of the Great Northern, threatened to do to Spokane, Washington, in 1892; Spokane quickly carne round to Hill’s way of thinking). If it pleased him to turn a snake-infested bog into a swaggering market town, all he needed to do was to mark the spot with a junction.

Nothing in the geography prepares one for the arbitrary suddenness of these prairie railroad towns. For mile after mile, the sagebrush rolls and breaks. The bare outcrops of rock and gumbo clay monotonously repeat themselves. Then, out of the blue, you catch the glint of the sun on the sheet-metal cowl of a distant grain elevator. You pass the frayed ship’s rigging holding up the screen of an abandoned drive-in theater. There’s just time enough to savor the idea of the enormous, flickering image of Marilyn Monroe scaring the coyotes into the next county, and you’re in town.

You’re here : in a bar on Main, with Rexall’s next door, and, across the street, a used-furniture showroom squatting in the remains of what was once the opera house. The essential coordinates of place are here. This is a distinct local habitation with a name. Yet something’s wrong. Why is here here ? Why is it not some where else altogether?

No special reason. One day in 1908, someone with a map on his desk thought it was about time to make another town, and so he sketched one in. Perhaps he was talking on the telephone, and the cross-hatched grid of the city-to-be simply drew itself on the paper where his spare hand happened to be resting. Perhaps the city’s name is that of the person he happened to be talking to. There is a town on the Milwaukee Road line named after a newspaper reporter who happened to be riding in the presidential car when Albert J. Earling was out on one of his naming sprees.

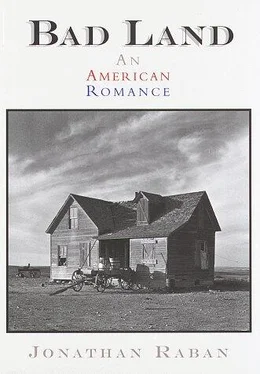

Nearly a hundred years after they were born, the accidental nature of their conception still haunts these towns. Their brick-work has grown old, the advertisements painted on the sides of their buildings have faded pleasantly into antiques, yet they seem insufficiently attached to the earth on which they stand. Leave one in the morning, and by afternoon it might easily have drifted off to someplace else on the prairie. Such lightness is unsettling. It makes one feel too keenly one’s own contingency in the order of things.

As the railroads pushed farther west, into open rangeland that grew steadily emptier and drier, the rival companies clubbed together to sponsor an extraordinary body of popular literature. For the land to be settled by the masses of people needed to sustain the advance of the railroads, it had first to be made real and palpable. In school atlases, the area was still called the Great American Desert — an imaginative vacancy, either without any flora and fauna, or with all the wrong flora and fauna. The railroad writers and illustrators were assigned to replace that vacancy with a picture of free, rich farmland; a picture so vivid, so fully furnished with attractive details, that readers would commit their families and their life savings, sight unseen, to a landscape in a book.

The pamphlets were distributed by railroad agents all over the United States and Europe. Every mass-circulation newspaper carried advertisements for them ( Fill in the coupon for your free copy by return of post …). They were translated into German, Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, Russian, Italian. They turned up in bars and barbershops, in doctors’ waiting rooms, in the carriages of the London tube and the New York El.

Some of these pamphlets were aimed at readers with firsthand experience of farming. But most were addressed to a wider audience. They dangled before the reader the prospect of fantastic self-improvement, of great riches going begging for want of claimants. They sought out the haggard schoolteacher, the bored machinist, the clerk, the telegrapher, the short-order cook, the printer, and promised to turn each of them into the prosperous squire of his or her own rolling acres.

“Unele Sam sends you an invitation …” The terms of the Enlarged Homestead Act, passed by Congress in 1909, after a great deal of lobbying by the railroad companies, were generous. The size of a government homestead on “semi-arid land,” like that of eastern Montana, was doubled, from a quarter-section to a half-section; from 160 acres to 320. One did not have to be a U.S. citizen to stake a claim — though it was necessary to become one within five years, when the homestead was “proved-up.” The proving-up was a formality that entailed the payment of a $16.00 fee and an inspection of the property to verify that it had been kept under cultivation. That done, the full title to the land was granted to the homesteader.

It was an astounding free offer by any reckoning. The only snag was the unfortunate name that early cartographers had written on the land. The name was mischievous. The northern Great Plains were not a desert — did not remotely resemble a desert. When James J. Hill, recently retired from the presidency of his railroad, wrote Highways of Progress in 1910, he was able to look back on what had already been accomplished in the region with benign pride:

The causes of [the Northwest’s] growth are to be found in the transfer of an immense population supplied by our own natural increase and by immigration, to enormous areas of fertile soil. It was like opening the vaults of a treasury and bidding each man help himself.

What the railroad pamphlets did was to point the way to the treasury and bid men help themselves.

The farther the pamphlets traveled, the more indefinitely suggestive they became. Minnesotan readers could measure the distance between themselves and Montana — they could imagine a dry and open country, and give a name and shape to shivering twigs of sagebrush. They had grown up with the language of American advertising and regional boosterism, and knew a sales pitch when they saw one. Faced with an astounding free offer, they looked, out of habit, for the small print.

But in London, Oslo, Kiev, where the text of the pamphlet was unpolluted by firsthand experience of the United States, the conjured world swelled before the reader’s eyes, free of the restraints of skeptical realism. In Europe, the cult of America made converts in every city slum and moldering agricultural village. People who had been ruined by the United States, like the smallholding farmers of southern Sweden, bankrupted by cheap Midwestern wheat, were among the most eager believers, their own misery itself a proof of the wonder-working providence of America. To readers like these, the pamphlets spoke as gospel.

In 1910, people had to furnish their American daydreams from a relatively scant supply of arousing details. There were letters home, articles in newspapers and illustrated magazines and a great deal of hearsay. The would-be emigrant was required to create an imaginary America that was palpable enough to become a real destination. By the time he bought his steamship ticket, he was bound for a land that existed in his head in rich, intricate and erroneous particularity.

Читать дальше