Jonathan Raban

Bad Land: An American Romance

For Paul and Sheila Theroux

(m. November 18, 1995)

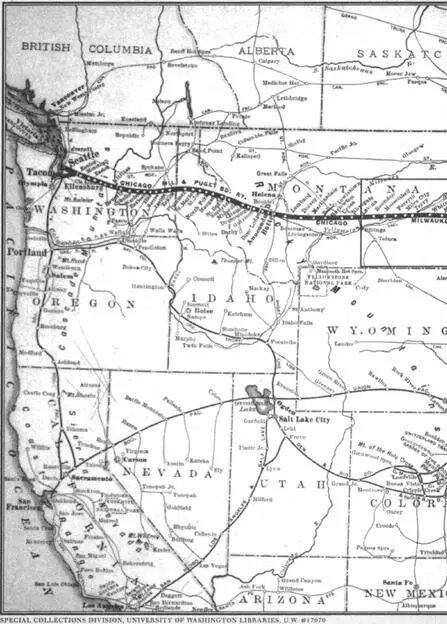

BREASTING THE REGULAR SWELLS OF LAND, on a red dirt road as true as a line of longitude, the car was like a boat at sea. The ocean was hardly more solitary than this empty country, where in forty miles or so I hadn’t seen another vehicle. A warm westerly blew over the prairie, making waves, and when I wound down the window I heard it growl in the dry grass like surf. For gulls, there were killdeer plovers, crying out their name as they wheeled and skidded on the wind. Keel-dee-a! Keel-dee-a! The surface of the land was as busy as a rough sea — it broke in sandstone outcrops, low buttes, ragged bluffs, hollow combers of bleached clay, and was fissured with waterless creek beds, ash-white, littered with boulders. Brown cows nibbled at their shadows on the open range. In the bottomlands, where muddy rivers trickled through the cottonwoods, were fenced rectangles of irrigated green.

Corn? wheat? alfalfa? Though I grew up in farmland, asthma and hay-fever kept me at an allergic distance from crops and animals, and it was with the uninformed pleasure of the urban tourist that I watched this countryside unfold. I loved its dry, hillocky emptiness. Here were space and distance on a scale unimaginable to most city dwellers. Here one might loaf and stretch and feel oneself expand to meet the enormous expanse of the surrounding land.

I stopped the car on the crest of a big swell and attacked a shrink-wrapped sandwich bought at a gas station several hours before. The smell of red dust, roasted, biscuity, mixed with the medicinal smell of the sagebrush that grew on the stony slopes of the buttes. I thought, I could spend all day just listening here — to the birds, the crooning wind, the urgent fiddling of the crickets.

The road ahead tapered to infinity, in stages. Hill led to hill led to hill, and at each summit the road abruptly shrank to half its width, then half its width again, until it became a hairline crack in the land, then a faint wobble in the haze, then nothing. From out of the nothing now carne a speck. It disappeared. It resurfaced as a smudge, then as a fist-sized cloud. A while passed. Finally, on the nearest of the hilltops, a full-scale dust storm burst into view. The storm enveloped a low-slung pickup truck, which slowed and carne to a standstill beside the car, open window to open window.

“Run out of gas?”

“No—” I waved the remains of the hideous sandwich. “Just having lunch.”

The driver wore a Stetson, once white, which in age had taken on the color, and some of the texture, of a ripe Gorgonzola cheese. Behind his head, a big-caliber rifle was parked in a gun rack. I asked the man if he was out hunting, for earlier in the morning I’d seen herds of pronghorn antelope; they had bounded away from the car on spindly legs, the white signal flashes on their rumps telegraphing Danger! to the rest. But no, he was on his way into town to the store. Around here, men wore guns as part of their everyday uniform, packing Winchesters to match their broad-brimmed hats and high-heeled boots. While the women I had seen were dressed for the 1990s, nearly all the men appeared to have stepped off the set of a period Western.

“Missed a big snake back there by the crick.” He didn’t look at me as he spoke, but stared fixedly ahead, with the wrinkled long-distance gaze that solo yachtsmen, forever searching for a landfall, eventually acquire. “He was a beauty. I put him at six feet or better. I could have used the rattle off of that fellow …”

With a blunt-fingered hand the size of a dinner plate, he raked through the usual flotsam of business cards, receipts, spent ballpoints and candy wrappings that had collected in the fold between the windshield and the dashboard. “Some of my roadkills,” he said. Half a dozen snake rattles, like whelk shells, lay bunched in his palm.

“Looks like you have a nice hobby there.”

“It beats getting bit.”

He seemed in no particular hurry to be on his way, and so I told him where I carne from and he told me where he carne from. His folks had homesteaded about eight miles over in that direction — and he wagged his hat brim southward across a treeless vista of withered grass, pink shale and tufty sage. They’d lost their place back in the “Dirty Thirties.” Now he was on his wife’s folks’ old place, a dozen miles up the road; had eleven sections up there.

A section is a square mile. “That’s quite a chunk of Montana. What do you farm?”

“Mostly cattle. We grow hay. And a section and a half is wheat, some years, when we get the moisture for it.”

“And it pays?”

“One year we make quite a profit, and the next year we go twice as deep as that in the hole. That’s about the way it goes, round here.”

We sat on for several minutes in an amiable silence punctuated by the cries of the killdeer and the faulty muffler of the pickup. Then the man said, “Nice visiting with you,” and eased forward. In the rearview mirror I watched his storm of dust subside behind the brow of a hill.

In the nineteenth century, when ships under sail crossed paths in mid-ocean, they “spoke” each other with signal flags; then, if sea conditions were right, they hove to, lowered boats, and the two captains, each seated in his gig, would have a “gam,” exchanging news as they bobbed on the wave tops. In Moby-Dick , Melville devoted a chapter to the custom, which was still alive and well on this oceanlike stretch of land. It was so empty that two strangers could feel they had a common bond simply because they were encircled by the same horizon.

It had not always been so empty here.

The few working ranches were now separated from their neighbors by miles and miles of rough, ribbed, ungoverned country, and each ranch made as self-importont a showing on the landscape as a battlemented castle. First, there was the elaborately painted mailbox — representing a plow, a wagon team, a tractor, a well-hung Hereford bull — set at the entrance to a gravel drive. A little way beyond it stood a gallows, with twenty-five-foot posts supporting an arched crosspiece emblazoned with the names of two or three generations of family members, along with the heraldic devices of the family cattle brands: numbers and letters, rampant and couchant — in western tolk, “upright” and “lazy.” In the far distance lay the ranch, its houses, barns and outbuildings screened by a shelter belt of trees. Trees! Here, where almost no trees grew of their own accord except along the river bottoms, these domestic forests announced that their owners had water, agricultural know-how, and long occupancy of the land. You could arrive at an accurate estimate of a given family’s income, character and standing in Montana just by looking at their shelter belt. Some were no more than a threadbare hedge of sickly cottonwoods, but one or two were as tall and dense and green as a bluebell wood in spring.

The families were so few, their farms so unexpected and commanding, that they mapped the land, stamping it with their names, much as England used to be mapped by its cathedral cities. Here , where a crew of surly heifers blocked the road beside the creek, was Garber country. A barred lazy A and upright T were burned into the hide of each animal — the family brand of the Garbers (“Gene-Fernande-Warren-Bernie”) whose grand ranch entrance I had passed eight or nine miles back. I honked, and was met by a unanimous stare of sorrowing resentment, as if I was trying to barge my way through an important cow funeral.

Читать дальше