The Nome Kennel Club maintains a snug shelter cabin at the west foot of the rugged Topkok Hills. Located in the middle of one of the worst wind areas on the trail, this cabin has saved more than a few snowmachiners and mushers over the years.

But today the blowhole is a toothless tiger and I have plenty of time to take in the scenery as we glide along the beach trail. After 12 miles we reach the Bonanza Ferry bridge and the Nome-Council Road. The history in this area is hard to miss; buildings and relics are everywhere. The remnants of the old city of Solomon, once a roaring boom town to rival Nome, are a mile inland. The bridge is flanked by the Last Train to Nowhere, the remains of three steam locomotives used during the early 1900s on the short-lived railroad from Solomon to Council.

Council, 35 miles northeast of Solomon and 15 northwest of White Mountain, had its own gold rush a year before the discoveries at Nome. John Wayne’s “North to Alaska” was filmed partly on location at Council. The movie’s theme song by Johnny Horton celebrated the gold “beneath that old white mountain just a little southeast of Nome.” The mountain was supposed to be Cape Nome, but nobody’s ever worried much about his geographic license.

From here to Nome the shoreline is strewn with old cabins now used as summer fish camps. The very beach over which we’re running was the magnet which drew thousands of miners to the area between 1898 and 1900. While gold abounded in placer deposits inland, mining it was expensive and difficult. When the precious metal was discovered in the sands of the beach itself, anyone who could wield a shovel and run a crude sluice box descended on Nome from around the world.

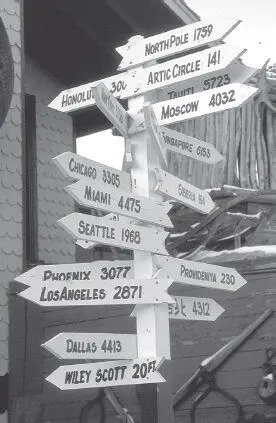

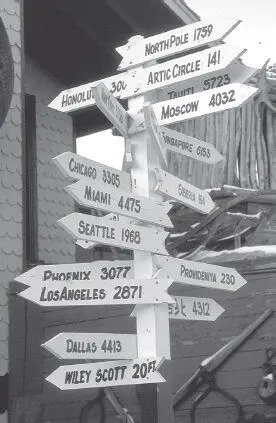

Nome is much closer to Tokyo and many cities in Asia than to many points in the United States. This signpost is a standard stop on all tours of downtown Nome.

This was what made Nome so different from other gold rushes: would-be miners could literally step from their ships onto the beach and look for their pay-streak with virtually no equipment or experience. Most went home broke in a few months, but a few made fortunes before the easy beach gold played out after a couple of years.

The harder-to-get placer gold was abundant, however, and the area is still a gold-mining center. One of the biggest mines in Alaska operates in a huge pit a mile north of downtown, just off the end of the airport’s main runway. In the summer dozens of small mines are reopened and hundreds of latter-day stampeders work claims from the beach to the mountainous backbone of the Seward Peninsula. There’s still lots of gold here; its lure has not dimmed over the years.

Nome has an aura unlike any other city in Alaska, or in the country, for that matter. It boasted more than 20,000 people in 1900 and was the largest city in Alaska. The town was wide-open 24 hours a day and sported the most notorious saloon row north of San Francisco; the legendary Wyatt Earp ran one of these establishments. In fact, the City of the Golden Beaches was probably the last hurrah of the Old West and was populated with many other refugees from the vanishing frontier down south.

In many ways the 1900s never ended out here. The town has an omnipresent look and feel of living with one foot in the past, combined with a civic outlook on life which can best be described as different if not downright zany at times. It’s likely there’s not another town in Alaska that collectively enjoys a good joke as much as Nome. This slightly warped sense of humor manifests itself all year in a series of goings-on which sometimes befuddle visitors who don’t understand it takes special people to live here, and a good laugh is one of the strongest weapons to fight off the wind, weather, and isolation.

Rookie Sonny King emerges from a relatively mild 50-mph ground blizzard between Topkok and Solomon in the 1997 race. The poles are trail markers. The Solomon blowhole has nearly killed mushers in past races, almost within sight of Nome. A natural wind tunnel, it can hurl 80-mph winds and blinding whiteouts.

Nome is the perfect place to finish the Iditarod, an ideal foil for too-urban, self-conscious, often-pretentious Anchorage. Nome is the Last Frontier’s last frontier town. As the dogs trot past the cabins lining the snowy road to Safety I realize the Iditarod is really the ultimate flight from modern civilization, requiring a complete break with many of the premises and assumptions which govern life in a nine-to-five world of cable television and home pizza delivery.

It’s nearly sunset as I approach the Safety Roadhouse standing by itself alongside the bridge across the frozen entrance to Safety Sound. As I pull into the drifted parking lot alongside a handful of snowmachines I know this is the beginning of the end of the journey. Nome is barely 20 miles up the road and the weather is perfect. Besides, I’ve been listening to KNOM radio on my Walkman and I know we’re expected.

Lisa arrives in a few minutes; her mother, Barb, whom I’ve met before, has been waiting anxiously. When Lisa finishes in a few hours they will be the first mother and daughter to have completed the race. I’m glad to have been part of it. I throw my dogs some well-earned chunks of beef and head inside for a steaming bowl of chicken soup and hot coffee. Most drivers don’t spend more than a minute or two here, but we’re in no hurry. Nome isn’t going anywhere. Besides, I’ve become so enmeshed with the dogs and the trail I want to enjoy every minute I have remaining.

The theme song of John Wayne’s North to Alaska celebrated the gold “beneath that old white mountain just a little southeast of Nome.” The mountain was really Cape Nome, between Safety Roadhouse and the city of Nome. A muskox herd forages atop the headland during the winter.

When we leave an hour later Lisa and I agree she will go first down Front Street. For her it’s a homecoming; for me it doesn’t matter where I finish — just getting here has been my only goal. I take the lead as we head to Cape Nome; we’ll swap when we get closer to town. Inevitably a couple of lines from the last verse of Hobo Jim’s Iditarod anthem roll through my mind: “Just pulled out of Safety, on the trail all alone….” Maybe I don’t fit his scenario exactly, what with Lisa on the road a half-mile behind, but it’s close enough for me.

Watching the dogs pulling smoothly and powerfully in front the sled, I almost wish we could go another few hundred miles. Unlike the front-runners who have no choice but to push their dogs, my guys are only now peaking. I’d give anything if I could start the race next year with these same dogs in exactly the condition they’re in right now.

For the last few miles into Nome, the trail runs along the shore of the Bering Sea before climbing the seawall to Front Street.

Now I understand how Ron Aldrich and Del Allison could run their teams on up to Barrow after they finished the Iditarod in 1979. For them it was just a continuation of the trail and I almost wish I could do something like it. Ron says he wants to run again next year for the big 25th Anniversary race and maybe we’ll do just that.

Читать дальше