After a thrill-packed hour and a half I finally ease the team off the flanks of Mount Kwiniuk and onto the beach at Walla Walla with all of our various appendages and appurtenances still in their appropriate places. The country has been beautiful and the scenery spectacular, but I don’t think the Elim mail trail will ever make it into the Guide Michelin .

I’ve been so busy maintaining my death grip on the handlebar I haven’t noticed I’ve outrun Lisa and Andy. I stop the team to wait for them and feed some frozen beef while I try to coax my adrenaline level back into its normal operating range. Fifteen minutes later Lisa pulls up; she’s still shaking from her E-ticket ride over the mail trail and also calls a temporary halt to the festivities.

We wait for Andy for quite awhile, growing more and more worried something has happened to him. Finally we hear a snowmachine coming from the direction of Elim. We flag down the rider and ask him if he’s seen a team on the trail behind us. To our immense relief he says a musher returned to Elim just before he left and is back at the now-closed checkpoint. Lisa and I don’t know if Andy has given up or is just resting his dogs as he’s done earlier on the race. In any event, he’s on his own now; besides, we’re not sure we’d survive the trip back to Elim to check on him.

We thank the snowmachiner, who’s on his way to White Mountain on an everyday 50-mile afternoon trip in the Bush, and shortly follow our fellow traveler up the first of the interminable grades leading to Little McKinley. After two miles of steady uphill slogging I’m glad I’ve got a lot of big males on the team. Nobody’s really even breathing hard and I only need to assist with a perfunctory pump once in awhile. Lisa, however, is having more difficulty with her smaller team and is doing a lot of walking, so I periodically stop and wait for her to catch up.

As we gain the top of the first hill we’re well above timberline; stretching to the west I can see the series of ridges we’re about to cross. Surprisingly, there’s not a breath of wind up here and the temperature is almost above freezing. The clement weather is unusual but certainly not unwelcome; this upland stretch is known for its extremes and we’re thankful for a lucky break after our tribulations around Unalakleet and Shaktoolik.

After another hour and a half of by-now-routine ups and downs we power up the final incline to Little McKinley itself and stop just before the steep three-mile downgrade to take in the view. Ice-covered Golovnin Bay lies below us, probing 20 miles northwest past the village of Golovin on its rocky point to our goal of White Mountain, nestled far inland under its wooded namesake hill alongside the Fish River.

Unlike the heavily forested eastern side of the mountains, the slopes below us and to the west as far as we can see are bleak and barren except for scrub. The only real trees from here to somewhere in Siberia are much further inland, limited strictly to sheltered slopes and river valleys.

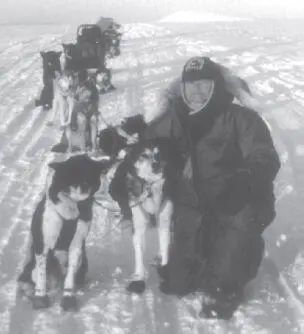

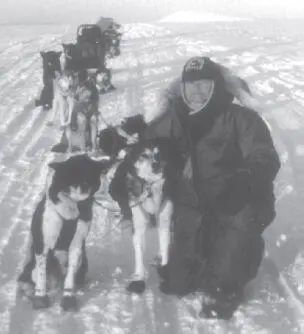

The author with Pullman (left) and Socks (right) atop Little McKinley in the 1996 race. Nome is less than a hundred miles ahead over a fast trail. (Photo by Lisa Moore)

The sun is just about to set over Topkok Head 35 miles to the west and the rich late-afternoon light gilds everything around us. On the western horizon beyond Topkok we can barely see the hazy outline of Cape Nome, now only 60 air miles away with Front Street and the burled arch only a few miles further on.

We hold a quick meeting of the tail-enders’ club and officially decide we can start to have fun now. For the first time since leaving Anchorage I really relax. We’re actually going to make it even if we have to hole up somewhere to wait out the approaching storm, of which we’ve so far seen no sign.

As the sun sets over the Russian Far East — only a couple of hundred miles away — we plunge down the hill toward Golovin. Shortly we pass the shelter cabin at the mouth of McKinley Creek and turn up the ice of the bay toward the village. The sky is crystal clear and the wind is dead calm; the temperature begins to plummet toward zero as the sun disappears. The trail is hard and fast and the lights of the village beckon invitingly.

Golovin is a small Inupiat Eskimo settlement of slightly more than 100 souls. The village was already old when Captain Golovnin of the Imperial Russian Navy sailed through this area in the early 1800s. The bay as well as the lagoon behind the town still retain the correct spelling of his name; the name of the village has been subtly changed over the years. Golovin was a full-fledged stop on the early Iditarods but now it is only a sign-in checkpoint and few mushers, at least in the front end of the race, spend much time here.

Lisa and I decide to stop in town to get into some warmer gear. I ask the checker about a place to change clothes and she says to wait a minute. Shortly she helps us park our dogs and then ushers us into her aunt’s house, where we are plied unmercifully with coffee, tea, hot chocolate, sandwiches, soup, cookies, offers of places to rest, and good conversation.

Here in Agnes Amarok’s snug home we find the warmest display of hospitality either of us has yet seen on the race. We are completely taken with the wonderful people of Golovin, several of whom stop through to say hello and offer encouragement and trail information.

We spend a couple of hours relaxing in this unexpected but completely welcome haven. As we chat it develops Lisa went to high school in Nome with the checker, and a couple of the older residents remember Ron from his early Iditarods; once again the big-state-small-world paradox manifests itself.

The awards banquet in Nome is still going on and we listen to it on the radio while munching sandwiches and sipping hot coffee. We figure this is a fair exchange for not making the party ourselves; we’ll take some extra time here and attend the banquet vicariously via KNOM radio.

Eventually we realize we must leave to get on to White Mountain, an easy 18-mile run across Golovnin Lagoon. Our hosts duly warn us about a potential problem which snared Martin Buser and DeeDee Jonrowe. It seems an inviting side trail leading to a hunting camp was marked similarly to the Iditarod before the race. Martin and DeeDee got confused and took it, costing them an extra hour and a half, and slipping DeeDee a place in the final standings.

We get specific instructions to avoid this: take the trail heading directly for the White Mountain airport beacon, easily visible for the entire run from Golovin. We figure this is about as simple as it gets and move out, promising to spend some time in Golovin on future Iditarods.

I take the lead out of town, carefully avoiding the false turnoff. Once out on the ice, the trail across the lagoon is ideal in every respect: straight as an arrow, well-marked, perfectly groomed, and utterly level. The temperature is perhaps 10 below zero and the dogs accelerate immediately to nighttime cruising speed.

In my headlight I can see an endless line of golden reflectors pointing northwest, precisely at the rhythmic green-and-white strobe of the White Mountain beacon on the horizon. Mariners throughout history have navigated by lighthouses just as we are using the beacon flash. This is also how pilots found their way at night up until the 1930s, following airway beacons just like this one across the darkened landscape before instrument flying was developed.

The sense of voyaging is inescapable. Socks and Pullman are up front and are following the well-defined trail as if they are on rails. The rest of the team is pulling so quietly and smoothly I almost don’t realize they’re there. We are on full autopilot, leaving me with nothing to do but ride along and keep myself amused.

Читать дальше