Alaska Dogs and Iditarod Mushers

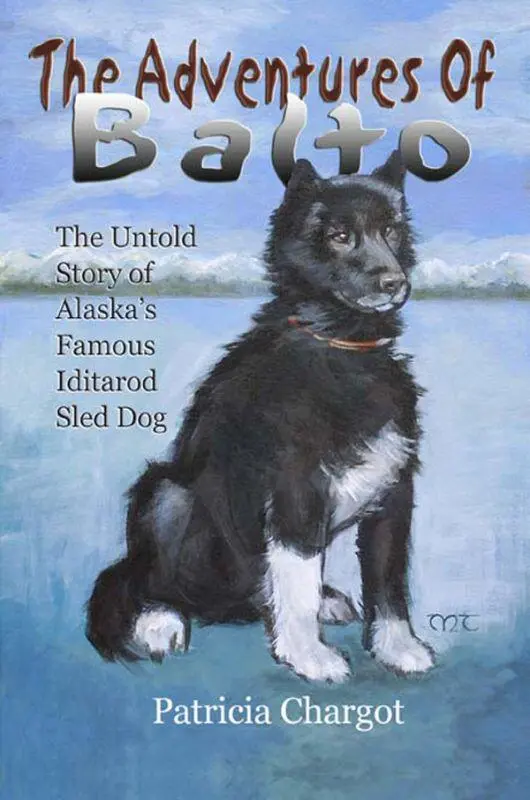

The Adventures of Balto: The Untold Story of Alaska’s Famous Iditarod Sled Dog

by

Patricia Chargot

For Per, my sweet Viking.

With special thanks to Steve Misencik of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History for his generosity in sharing Balto’s story. His enthusiasm sparked mine.

Thanks, too, to Martha Thierry for capturing Balto’s essence for the cover of this book.

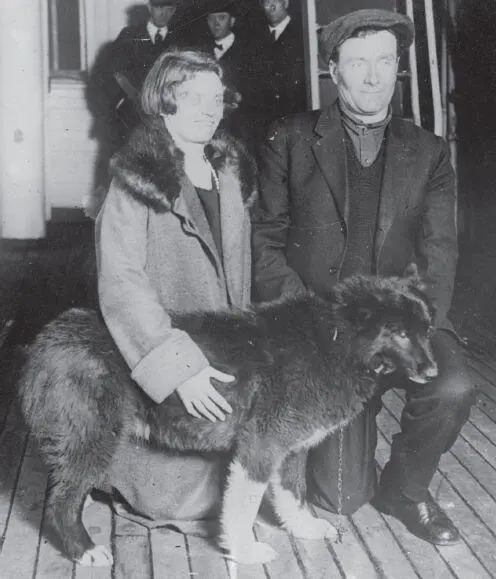

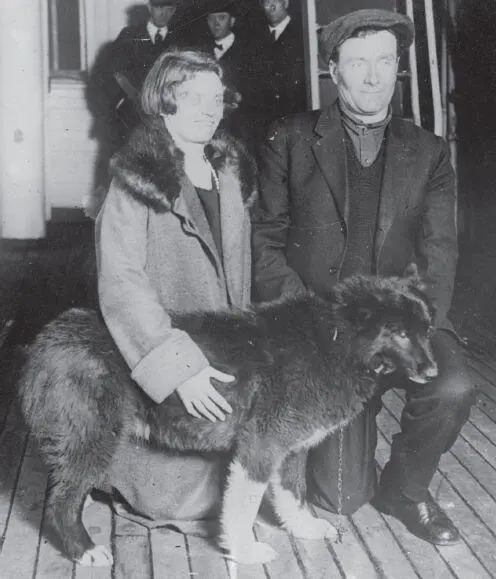

Accompanied by his master, Gunnar Kaasen, and Mrs. Kaasen, Bal-to, the famous Alaska trail dog, on arrival in Seattle, Washington aboard the steamship Alameda , and was given the freedom of the city. Then, he soon left for Mount Rainier to become a motion picture star. Courtesy of Special Collections, Cleveland University Library.

Balto. The great Alaska sled dog has been dead since 1933. But he still stands larger-than-life on Dogdom’s Mount Olympus, where the world’s great canines are immortalized.

He’s up there with Barry, the brave Saint Bernard that rescued mountain travelers buried by avalanches in the Swiss Alps. He shares a golden kennel with Hachiko, Japan’s favorite dog, that faithfully searched for his dead master for years outside a Tokyo subway station. His name echoes down the long dog run of history with the brave Newfoundland Tang’s, the Earth-orbiting Laika’s, the loyal Skye terrier Greyfriars Bobby’s.

Yet few people know Balto’s true story. Only one small part has been told, and even it has been distorted.

Over the decades, several Balto books have been written. There’s even a Balto animated movie, but it, too, is largely fiction. (Balto was NOT part wolf!) Like the books, the movie leaves off where this book begins — and tells the best part of the story.

Balto was only three years old when he helped carry serum across Alaska from Nenana to Nome to save the town’s children from diphtheria. As leader of the last dog team in the life-saving relay race, he became an overnight sensation — a BONEa fide international celebrity.

But so much more happened after that. Balto lived for eight more years, experiencing the happy surprises and unexpected sadnesses found in every long life — animal or human.

His days unfolded like a sled expedition to the North Pole, carrying him in an exhilarating rush over smooth snow one minute, an icy hummock the next. And how does the new story end? With a heart-thumping surprise that you can’t imagine and neither could have Balto.

So hook up your harness, step into Balto’s booties — the little fleece socks sled dogs wear to protect their feet — and mush off to Chapter One.

Whoosh.

Nome about the time of Balto’s historic run.

Courtesy of Carrie M. McLain Memorial Museum

Chapter One

Down and Out in a Dime Museum

The dogs’ whimpering was too soft to be heard from the street. Outside the old storefront, the party decade was roaring — not just in Los Angeles, but across the country.

It was the wild, jazzy, fun-filled Roaring Twenties. Flappers in short skirts were kicking their legs and twirling the long strands of pearls they wore around their necks. The economy was booming — lots of people were making money and spending it on having fun.

But there was no party going on at the storefront: no jumping, bellowing, yipping. No running, falling, tumbling. No enthusiastic barking — and not one note of joyful husky singing.

The converted store was a “dime museum,” a cheap sideshow wedged among gambling dens, illegal drinking dives and other sleazy joints. For 10 cents, visitors — mostly out-of-town businessmen — could ogle an “animal curiosity” — seven famous Alaska sled dogs.

The dogs were Balto, Fox, Alaska Slim, Billy, Sye, Old Moctoc and Tillie, the only female.

Just two years earlier, in February 1925, the team had been heralded as heroes on the front pages of the world’s newspapers for saving the children of Nome, Alaska, from a deadly diphtheria epidemic.

In Washington, D.C., the U.S. Senate had suspended official business to listen to stories, poems and songs about the dogs and their young driver, Gunnar Kaasen.

But now it was February 1927. Five of the team’s original 12 dogs were gone, and Kaasen had mysteriously disappeared.

The seven remaining dogs were has-beens — even Balto, the bear-like leader with the cute white markings that was known to children across America.

Thousands of families had Balto bookends and used Balto dog food dishes or cat food dishes to feed their pets. But did they think of Balto?

The brave dogs had been forgotten — some would say, shamelessly left to die. Small, hot and windowless, the dime museum was no place for dogs. But it was a nightmare for huskies, which are most comfortable in temperatures of 10 to 20 below zero.

In Nome, the team had lived like other sled dogs — in a huge kennel in the middle of a snow-covered field. The snow was deep and made the dogs want to jump and run. The air was crisp and crystal-clear. It sharpened their already keen senses of taste and smell.

But there was no fresh air in the dime museum, not a ripple of breeze or tiny icebox blast of chill. The stifling conditions were draining the dogs’ life force, almost as if some great invisible moose, their dreaded enemy back in Alaska, was slowly stomping them senseless.

After weeks of confinement, the dogs were thin, weak and miserable. Their lustrous fur had dulled, and their once strong pulling muscles had shrunk. One by one, they had sunk into a lethargy, a state between wakefulness and sleeping.

There was no stimulation of any kind, nothing to rouse their spirits. So they lay dreaming of faraway Alaska: of soft, sub-Arctic sunlight, sub-zero temperatures, the tantalizing scents of reindeer, fox and rabbit.

They had come such a long way since the life-saving serum run. Now, they were unable to save their own lives. Tied to their beloved sled in a musty back room of the museum, they wondered: “Is this the end of the trail?”

Chapter Two

Back to the Beginning: Balto’s Early Life and the Serum Run

Leonhard Seppala (SEP-luh) loved Siberian huskies.

It was 1922, and the friendly, easy-to-train breed hadn’t even been introduced yet to the American Kennel Club in New York — let alone officially recognized.

But up in Nome, the little gold town of the far north, Seppala already had raised and bred more Siberians than any other Alaskan musher.

The small but strong Norwegian had been smitten by the small but strong dogs in the early 1900s, when a friend had given him 15 Siberian pups and adult females — all imported from eastern Siberia, a long, watery reach across the Bering Strait from Nome.

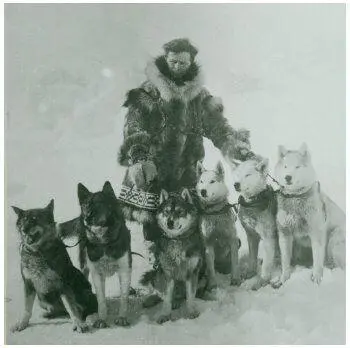

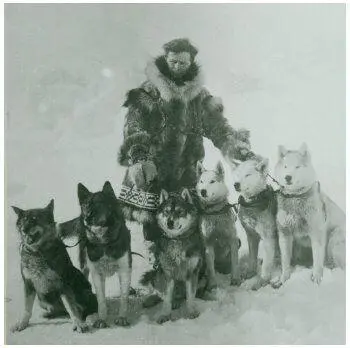

Leonhard Seppala with a team of dogs. The dog on the far left is Togo, and the dog on the far right is Fritz. Courtesy of Carrie M. McLain Memorial Museum

But some Siberian huskies were better than others — smarter and faster, with greater endurance and better dispositions. Like other husky breeders, Sepp — as Seppala’s friends called him — felt he could tell “A” dogs from “B” dogs as pups. “A” dogs were used for long-distance runs and races and bred; “B” dogs were neutered and consigned to hauling freight.

Читать дальше