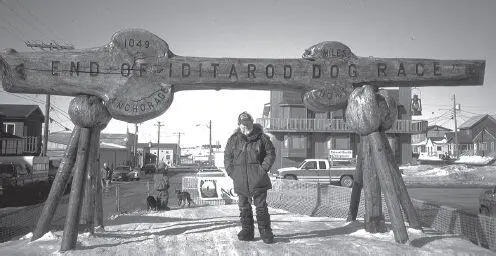

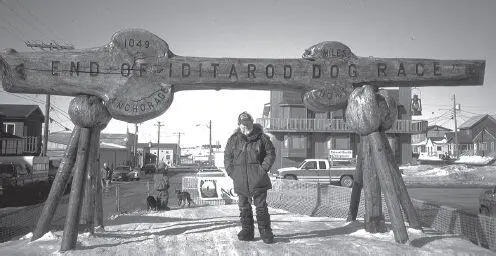

The author stands under the burled arch at the finish line in Nome after completing the Iditarod. The arch is moved from its normal resting spot in front of the Nome City Hall to the middle of Front Street for two weeks every year during the Iditarod. (Note the Widow’s Lamp hanging from the right side of the crossbar.)

Preparing for the race and running it has changed my outlook on more things than I would have thought possible. My concept of time and space founded on years of flying and other motorized travel has been irrevocably altered. The world has become a startlingly large and three-dimensional place, full of alternate but perfectly valid realities. Having now actually traversed Alaska on the ground at a respectful pace, I have an appreciation for its vast size and many different faces I could have gained no other way.

And I have learned that even at the pace of the old sailing ships a huge world can be conquered with a little patience and determination. Indeed, my perspective of just about everything has been remolded over the past two years and fired in the furnace of the last two weeks. I know it’s trite to say I’ll probably never look at anything again the same way, but it’s true. Most of all, I regret the race is actually over; part of me wants it to go on and on, to find more new trails to explore. But that will have to wait for the future.

I end up in the dog lot at the foot of Front Street. My guys seem to know I’m coming and are watching me as I walk up. I stand for a moment to admire them. We’ve learned volumes about each other over the past couple of weeks. I walk back to dignified old Buck, indestructible Rocky, ever-forgiving Yankee, half-goofy Bear, and moody Wild Thing and give them all a hug.

I continue along the line, thanking each one: dapper Kisser, one-eyed Steel, stalwart Pullman, still-playful Silvertip, and crazy little Maybelline, whose bouncy attitude and wraithlike appearance, I now know, conceal cast-iron toughness. I wish Lucky, Bea, Batman, Panda, and Diablo could be here, too; they did their best and deserve just as much.

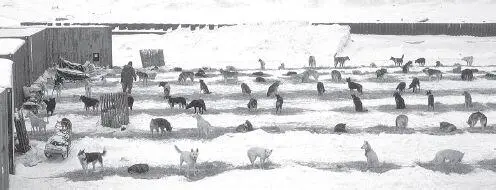

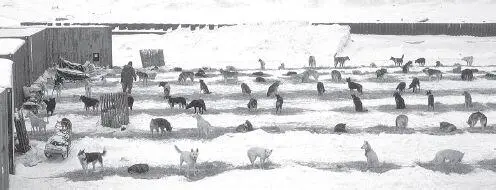

The huge dog lot at the west end of Front Street in Nome is the end of the trail for hundreds of weary dogs after their 1,200-mile treks from Anchorage. From here, teams are trucked to the airport for their rides home.

My team has become more than a family to me. We’ve shared adventures I couldn’t have imagined even a month ago. My dogs have shown everyone they can run the toughest race on earth. They have demonstrated incredible strength, indomitable courage, and total loyalty. They have done everything I’ve asked of them and more. I don’t know of anything I can do to reward them sufficiently. This hasn’t been my triumph, but theirs.

Finally I stop in front of Socks. He casually yawns, stretches, and puts on his best world-weary-traveler expression as if to say, “Been there, done that. So what else is new?” At the end of it all, it’s the old master who brings me back down to earth. He’s done this more times than I probably ever will and he’s not swayed by anything we’ve been through. Indeed, it’s as if he’s reminding me we haven’t really gone through anything worse than most of the mushers and teams that finally make it to Nome.

At that moment, gazing into Socks’ wise eyes, all the abysmal trails, broken hands, sleepless nights, windswept tundra, freezing fingers, treacherous overflow, and endless little frustrations — all the things which drove me to distraction and led me to the brink of tossing everything away — are swept into the insignificance they so richly deserve. It really was fun. We’ve got to do this again!

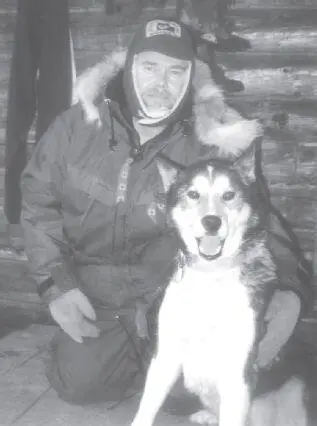

I plop down beside Socks and we wrestle in the straw as he tries to lick my face. If anyone is watching at this late hour, I’m sure they think I’m quite mad. And you know, they just might be right.

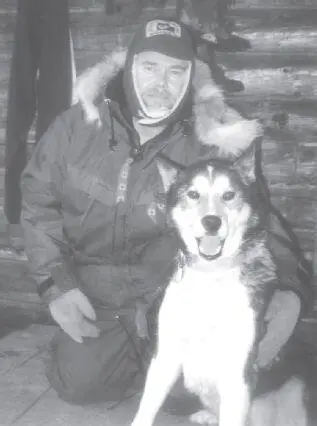

Don Bowers and Socks.

Kim Hanson did indeed make it to Nome in the 1998 Iditarod, with Pullman leading the way up Front Street. Socks helped lead most of the way but Kim had to drop him at Elim because his age was finally starting to slow him down as the remainder of the team began the final push for Nome. However, the Iditarod Air Force gave him a free flight to Nome and the Big Dog Lot one more time, where he was waiting in Nome for Kim and his teammates. He is now a comfortably retired couch potato at Bert’s house in Anchorage and is always glad to tell his tales of the trail to anyone who will toss him a dog biscuit.

Linda Joy finally made it to Nome in 1998—on her third try. It’s hard to imagine anyone who worked harder for a ride up Front Street and a stop under the burled arch. I wasn’t as fortunate in my own 1998 run. Maybelline injured her foot and my other main leader, Polar Bear (who went to Nome with Ron in 1994) developed a bad internal infection. Moreover, I was sick most of the time. Everything finally reached the breaking point and I finally had to scratch at Nulato. As it turned out, I had walking pneumonia and wasn’t able to shake it for three miserable months.

For the 1999 Iditarod, I put together a very strong team designed specifically to get me to Nome no matter how badly I screwed up. Maybelline went again, along with Polar Bear and my new main leader, Cutter, whom I bought from John Barron in the summer of 1998. I even leased a backup leader, Harley, from Lynwood Fiedler. Behind them was a tough crew including Iditapups Bonnie, Clyde, and Squeaky. Iron Dog, from my 1997 team and arguably one of the best sled dogs I’ve ever seen, was the team’s elder statesman at almost 9 years old.

The 1999 race turned out to be the hardest race I have ever run. Even Jeff King said it was the toughest he’d seen in more than a decade. We began with minus-100 chill factors heading up to Rainy Pass, and continued with open water and slick ice coming out of Rohn, followed by bitter 50-below temperatures that forced one musher to scratch at McGrath with severe frostbite. We ran into more 50- to 60-below cold on the way to Iditarod, and then punched through a storm on the way to Shageluk.

After a blizzard heading out of Kaltag, the temperature dropped to 50 below again at Old Woman. Then things really got interesting out on the coast, with howling ground blizzards and bone-numbing cold. Our small group of tail-enders got into a particularly bad storm on the way from Shaktoolik to Koyuk, with 60-mph winds directly in our teeth the whole way, accompanied by near-zero visibility out on the sea ice.

We had to rope teams together to keep them from wandering off the trail. It was the worst situation I’ve ever been in, and potentially lethal. But Dr. Jim Lanier, a pathologist from Anchorage and a seasoned Iditarod veteran, worked his leader flawlessly through the storm and led us all to safety. It took us 18 hours to go 45 miles.

The author’s long-suffering volunteer handlers pose before the restart of the 1996 race. Left to right are Julie and Mike Pannone, Doug Grilliot, Don Bowers, Jeannette Keida, Lindsey Hanson, Kim Hanson, and Misty Hammond. Kim Hanson will be the youngest woman to run the Iditarod when she heads to Nome in 1998.

Читать дальше