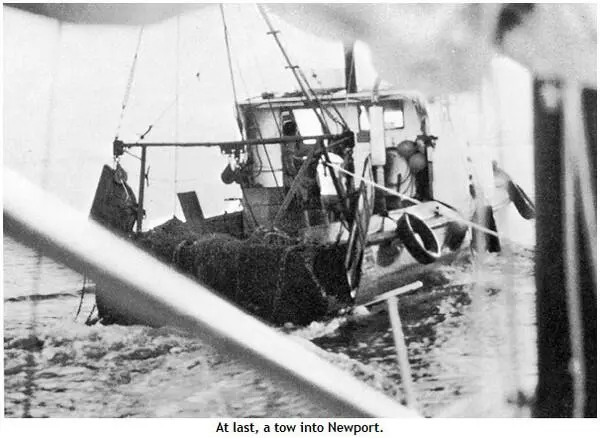

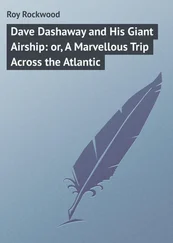

At six o’clock I heard an engine. Reception committee? Fishing boat. He was on his way out for his day’s work, passing a hundred yards to starboard. I hailed him and asked if he would call Goat Island Marina on his radio and ask them to come and get me. He said he would, and I settled down with my coffee again. A couple of minutes later, he had turned and was coming alongside.

“Nobody’s up,” he said. “Throw me a line, I’ll take you in.” The only other person aboard his boat was a girl.

“I envy you your crew,” I said. “I haven’t seen one of those for six weeks.” She laughed and made my line fast.

As we moved up the river a huge, red sun rose behind the spires of Newport. I stood on the deck and looked at the houses and green shore. It seemed unreal, a New England Disneyland, constructed of papier-mâché. We approached the marina’s fuel dock. A lone figure stood on the pier, holding a towel. I shouted at him to take a line. He did. He was waiting for someone to come and unlock the showers. I called the reception center. No answer; it had closed the day before. Customs wasn’t up yet. No need to wake Angela at this hour. I lurched back to the yacht on my new land legs and pottered around the decks, sorting ropes, then went below for another cup of coffee. I was too excited to sleep. A voice from above. I stuck my head up. A smiling face greeted me.

“I’m Pete Dunning; I run the marina; I think you’re the sixty-third boat in. Congratulations.”

“Where’s Mike McMullen?”

“He hasn’t been reported since the start of the race.”

I knew it. I think I had known it all along.

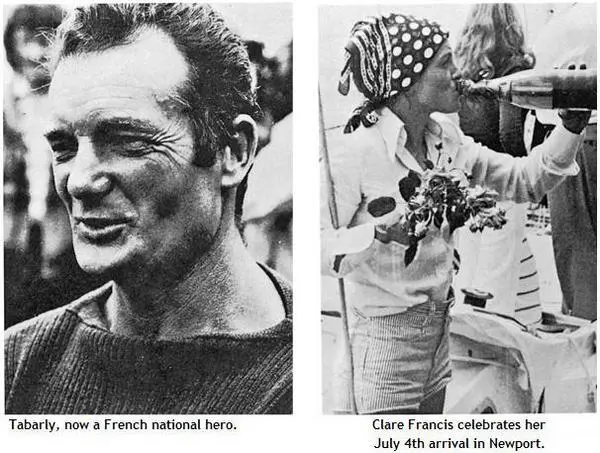

I had my first hot shower in six weeks, and Angela turned up soon afterward, having been rung by Pete Dunning. I got all the news: 125 boats had started the race; I had finished sixty-third; thirty-six had retired in various stages of damage; five had sunk, but their skippers were rescued; Mike Flanagan was lost and Mike McMullen was missing. Several other boats had not been reported but were eventually accounted for.

There was much discussion about what had happened to Mike McMullen. It was the consensus among those who knew him that he would not have taken his own life, even after having lost Lizzie. He seemed too good a yachtsman and too familiar with his boat and her limitations to have lost her in heavy weather. No collision had been reported. It is my own view that he went in some simple, everyday way, probably falling overboard like Mike Flanagan and like Brian Cooke the year before. That can happen to anybody, no matter how good he is. It is unlikely that anyone will ever know for sure, of course. The only possible consolation for any of his friends is that, depending on the way things really are, he might be with Lizzie. Anyone who knew them will spend the rest of his life missing them.

I pottered around Newport for a couple of weeks, getting small repairs done to Harp. My mother had been in Newport when I arrived and said she was getting tired of the family business. I had decided to sell the yacht and spend some time reorganizing things and getting her retired. I had a novel to finish, too, and the day after I arrived in Newport I talked with Ron Holland about a new boat for the next race, a bigger and faster boat. It was a very satisfying experience to finish the race, but I wanted to do it again, and faster.

Newport is a pleasant and hospitable place. Angela and I saw a lot of Peter Crowther of Galway Blazer and his girl, Pauline, and David Cowper of Airedale and his wife, Caroline. Jerry Cartwright and his wife, Kay, had a lot of the competitors over for dinner, and other dinner parties took place on the various yachts and at the Black Pearl on Bowen’s Wharf.

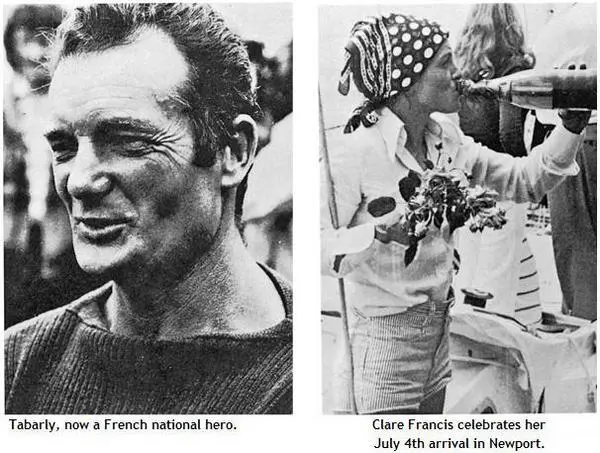

There was much warm camaraderie among the finishers, and each time another yacht finished, there was much shaking of hands and swapping of stories. Most of the early finishers had gone by the time I reached Newport, but many competitors were still there. A lot of them left the day after my arrival to return via a race to Horta, then France. Tom Grossman of Cap 33, who had finished fifth, came down on a visit from Boston. The people of Newport invited us to beach parties and made us feel welcome. They had had an active summer, what with the Tall Ships, then us.

Angela came back to Georgia with us for a few days before returning to London and her job on The Observer.

The race rules are being rewritten, probably to exclude giant yachts, and that may be for the best. There has been the usual chorus from some of the yachting press that the race be abolished or made into a two-man event. No matter what is said, it seems impossible to make them understand what this race means to the people who compete in it. Many human beings need adventure, real adventure, personal adventure, and, sometimes, as in our case, solitary adventure. Some men and women have always needed that, finding their own physical limits without the aid of bearers and Sherpa guides, searching out their own emotional and spiritual boundaries in places where there is no one to answer to but God. As our society grows and our environment shrinks, there will be more and more little men who will wish to deny us that. Many of them have public or editorial platforms and they will use them to attack this event. They must be ignored.

It is interesting to note that at the start of the race, where chaos had been predicted, not one untoward incident occurred which could be attributed to the size of the race, its organization, or the single-handedness of its entries. During the remainder of the race only two collisions with ships occurred, one of them not serious, one resulting in the sinking of the yacht and the subsequent rescue of her skipper. Another competitor, Nigel Lang in Galadriel, had the truly incredible experience of colliding with another single-handed yacht, not a competitor, hundreds of miles out in the Atlantic. Neither was seriously damaged.

Two lives were lost, the first ever in this event. It was inevitable that it would happen in one of these races, and now it has. Both men knew that it might, though neither probably expected it would happen to him. Both, in a sense, died defending the right of men to risk dying in adventurous living.

No one has proposed, with any effect, that motor racing be prohibited or that men stop trying to climb Everest. It is simply accepted that those who participate in these enterprises do so at their own risk, and good luck to them. Those of us who race single-handed ask no more than that. Leave us alone; ignore us, if you like, but let us get on with it.

Let us, as Jack Oddling-Smee, commodore of the Royal Western Yacht Club, has said, “enjoy and profit by what must surely be one of the last great freedoms granted to us in this ever contracting world.”

Interior Photo Credits

1, 2: Photograph by Ron Holland

3 : Chart reproduced with permission of The Observer

4: Photograph courtesy of Cruising World

5: Photograph by Helen Simpson

6: Photograph by Johnathan Eastland

7: Photograph by Chris Smith/ The Observer

8: Photograph by Chris Smith/ The Observer

9: Photograph by Chris Smith/ The Observer

10: Photograph by Chris Smith/ The Observer

11: Photograph courtesy of Cruising World

Читать дальше