Twenty-four hours later, however, we didn’t have a headsail anymore. The halyard on which it was flying parted at the mast sheave, probably because, in an effort to get the luff of the sail tight, I had winched it up too much and it was carrying too much of the weight of the mast. I was afraid to set the sail on another halyard — I was running out of them — and we made little progress during the night under the reefed main only.

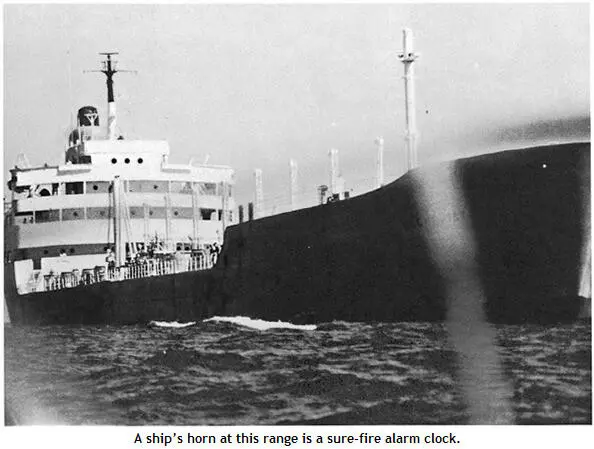

I decided to have a go at getting my VHF transmitter working with spare batteries from my signaling lamp. They were six volts each; six plus six equaled twelve, I reasoned, and the VHF worked on a twelve-volt current. I wired the two batteries together, hooked them to the radio, and it worked! At least, I was getting crackling noises. I didn’t want to try transmitting until I could see a ship, since the batteries were small and surely wouldn’t last long.

By morning it was clear that under the present sail plan we could sail either to Newfoundland or to Bermuda but not to Newport, unless we got a radical wind shift, and I wasn’t going to count on that. The only alternative seemed to be to repair the forestay in some way so that we could set a headsail, a job which seemed clearly impossible. It was bad enough that when the stay was unshackled from the toe rail it would start thrashing about again; but the main problem would be getting the stay to stretch enough to reach the forestay tack. I had found the cause of the failure: a deck eye which fitted into the bottom of the forestay had come unscrewed. First, I removed the deck eye from the forestay tack and tried to screw it back into the bottom of the stay. The threads were stripped. It would go part of the way in, then freewheel when turned. I spent two hours, lying on my side on the foredeck, draped over a spinnaker pole, trying to get the thing screwed back in. Finally, using a large screwdriver for leverage, I managed by putting pressure on it and turning at the same time, to get it most of the way in. But I had no way of knowing if the threads would hold and keep the same thing from happening again.

Now I had to try to stretch the forestay far enough to reach its deck fitting. The logical thing to do, of course, was to ease off the backstay, then crank down on the halyards forward, bending the mast until it reached. But I knew that would not get it close enough. O.H. and I, when Harp had been relaunched at the beginning of the season, had had one hell of a time getting the backstay to reach under similar circumstances, and that was with two of us pulling on it and no sea tossing us about. I would have to find another way.

My eye fell on the reefing line, which had broken when the stay went. This was a length of flexible wire rope with a rope tail spliced to one end for ease of handling. I took the block normally used for the spinnaker foreguy and shackled it to the forestay tack fitting, then ran the reefing line up through it and tied it around the wire drum at the bottom of the forestay. I took the rope tail back to a winch and cranked it as tight as I could, then went back to inspect the angle at which the line was drawing the forestay toward its fitting. It looked right, but there was still a twelve-inch gap between the end of the stay and the deck fitting. I went back to the cockpit and cranked each halyard down as tight as I could, then cranked on the reefing line again. It was working. I loosened the backstay even more and cranked down on all the winches again. The gap was now only about two inches. Was it possible this was going to work?

I cranked still further and the reefing line parted. It wasn’t going to work. I was going to have to sail to Newfoundland and try to keep from starving to death while I was doing it. I ran the line through the block again and retied it, then went back and started easing off the backstay even more, frightened stiff that I would turn the wheel one thread too many and the backstay would go. I eased it about two inches beyond where I thought it would be safe, then, one by one, cranked down on the halyards again, then the reefing line. I went forward to inspect the gap. The deck eye was one-fourth inch from the position where the clevis pin would slip in to secure it. Summoning up all the strength I had, I squeezed the eye into the gap. The clevis pin went in. With trembling hands I secured it with a split pin, and we had a forestay again.

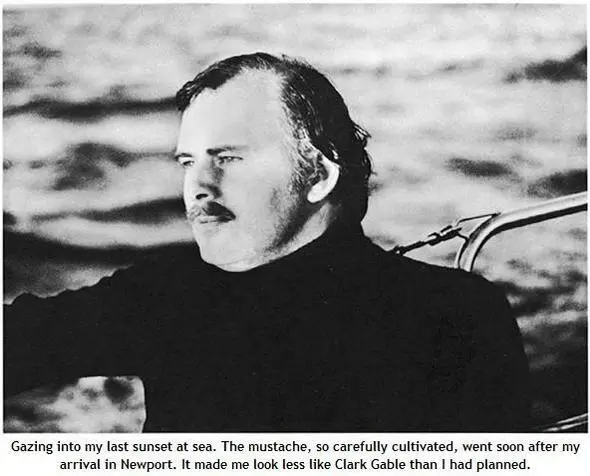

I couldn’t believe it. I had done something that two men shouldn’t have been able to do in a seaway. Could Robin Knox-Johnston have done this? (Of course he could, and in half the time.) The job had taken me from ten that morning until early evening, and I was too exhausted to hoist a foresail, so we slogged on overnight under main only. The next day was the sixth, the day I had planned to arrive in Newport, and we had drifted thirty-five miles to the northeast, pushed by the Gulf Stream. When the forestay broke we had been about four hundred miles from Newport, on about the latitude of Cape May. Now we were farther north, and I was worried about being headed again, as we would not be able to point high to windward with the present state of the rigging.

On Friday morning I thought I would try to pick up Nantucket Lightship, as we were getting close to being within radio direction finding range. I couldn’t hear Nantucket Lightship, but I was picking up another signal loud and clear. I checked the chart in Reed’s, showing all the New England radio beacons, and none of them matched the Morse code I was hearing. I began running through the lists of other east coast beacons, and in a moment my finger froze. I was hearing a radio beacon on the coast of North Carolina, and it had an effective range of a hundred miles. Had I, through some navigational blunder, approached the coast in the wrong place? Was I really off North Carolina? I began twirling dials furiously, weak with apprehension. I found another beacon and hurriedly looked it up. Cape Cod Light. I nearly fainted. Apparently, some freak atmospheric condition had allowed me to pick up the North Carolina beacon so clearly. For confirmation, I switched on the Zenith and started looking for commercial stations. The thunderstorms had caused so much interference that I had been unable to pick up anything except shortwave for several days. I found a station in Lynn, Massachusetts. I felt better.

Now my biggest concern was being becalmed. After the violence of the thunderstorms, we were down to about a Force two and it was coming from, of all places, the east. I got up a spinnaker, hoisting the heavier all-rounder, because if the wind rose I didn’t want to do another spinnaker change. We ran for most of the day in a light breeze, then, about sunset, the wind began to rise and go around. Soon we were close reaching at about seven knots and I was steering, because Fred couldn’t handle the helm under those conditions. I took the spinnaker down at dark and got up the number-two genoa, hoping that the dodgy forestay fitting and the two halyards still taken forward to the toe rail would keep the mast up. We managed an eighty-mile run that day, and I was pleased and relieved. That night, after dark, I thought I could detect a change of color in the water. The edge of the Gulf Stream is easier to find in the north than in the south. The water temperature and the color change very quickly at the edge. Next morning, the color was a dirty brown instead of the deep blue to which I had become accustomed.

We had the mast, we had a foresail, and we were out of the Gulf Stream. Newport lay ahead. We were finally in the home stretch.

Читать дальше

Читать дальше