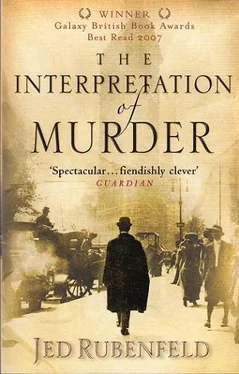

Jed Rubenfeld - The Interpretation of Murder

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jed Rubenfeld - The Interpretation of Murder» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторические приключения, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Interpretation of Murder

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Interpretation of Murder: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Interpretation of Murder»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Interpretation of Murder — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Interpretation of Murder», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'It's possible, my boy, except for one thing: the girl's behavior on the roof was already entirely and completely hysterical.' Freud drew another cigar from his pocket, thought better of it, and put it back. 'Let me offer you a definition of the hysteric: one in whom an occasion for sexual pleasure elicits feelings largely or wholly unpleasurable.'

'She was only fourteen.'

'And how old was Juliet on her nuptial night?'

'Thirteen,' I acknowledged.

'A robust, fully mature man — of whom we know nothing other than that he is strong, tall, successful, well-made — kisses a girl on the lips,' said Freud. 'He is obviously in a state of sexual arousal. Indeed, I think we may be confident that Nora had a direct sensation of this arousal. When she says she can still feel this Banwell pulling her body against his, I have little doubt what part of the man's body she felt. All this, in a healthy girl of fourteen, would certainly have produced a pleasurable genital stimulation. Instead, Nora was overcome by the unpleasurable feeling proper to the back of the throat or gorge — that is, by disgust. In other words, she was already hysterical long before that kiss.'

'But mightn't Banwell's advances have been — unwelcome?'

'I very much doubt they were. You disagree with me, Younger.'

I did disagree — strenuously — although I had been trying not to show it.

Freud went on. 'You imagine Mr Banwell thrusting himself on an unwilling and innocent victim. But perhaps it was she who seduced him: a handsome man, her father's best friend. The conquest would have appealed to a girl her age; it would likely have inspired jealousy in her father.'

'She rejected him,' I said.

'Did she?' asked Freud. 'After the kiss, she kept his secret, even after regaining her voice. Correct?'

'Yes.'

'Is that more consistent with fearing repetition of the event — or desiring it?'

I saw Freud's logic, but the innocent explanation of the girl's behavior did not yet seem refuted. 'She refused to be alone with him afterward,' I countered.

'On the contrary,' rejoined Freud. 'She walked with him alone, two years later, by the shore of a lake, a romantic location if ever there was one.'

'But she rejected him there again.'

'She slapped him,' said Freud. 'That is not necessarily a rejection. A girl, like an analytic patient, is required to say no before she says yes.'

'She complained to her father.'

'When?'

'Immediately,' I stated, a little too immediately. Then I reflected. 'Actually, I don't know that. I didn't ask.'

'Perhaps she was waiting for Mr Banwell to make another attempt on her, and, when he did not, she told her father out of pique.' I did not say anything, but Freud could see I was not entirely persuaded. He added, 'In this, my boy, you must bear in mind that you are not disinterested.'

'I don't follow you, sir,' I said.

'Yes, you do.'

I considered. 'You mean I wish Miss Acton to have found Banwell's advances unwelcome?'

'You have been defending Nora's honor.'

I was conscious that I continued to call Miss Acton 'Miss Acton,' whereas Freud called her by her first name. I was also conscious of a rush of blood to my face. 'That is only because I'm in love with her,' I said.

Freud said nothing.

'You must take over the analysis, Dr Freud. Or Brill. It should have been Brill in the first place.'

'Nonsense. She is yours, Younger. You are doing very well. But you must not take these feelings of yours so seriously. They are unavoidable in psychoanalysis. They are part of the treatment. Nora is very probably coming under the influence of the transference, as you are of the counter- transference. You must treat these feelings as data; you must deploy them. They are fictitious. They have no more reality than the feelings an actor generates onstage. A good Hamlet will feel rage toward his uncle, but he will not mistakenly suppose he is actually angry at his fellow tragedian. It is the same with analysis.'

For a time, neither of us spoke. Then I asked, 'Have you ever had — feelings for a patient, Dr Freud?'

'There have been times,' Freud replied slowly, 'when I welcomed such feelings; they reminded me that I was not altogether past desire. Yes, I have had some narrow escapes. But you must remember: I came to psychoanalysis when I was already much older than you, which made it easier for me. In addition, I am married. To the knowledge that these feelings are factitious, there is added, in my case, a moral obligation I could not violate.' It will seem ridiculous, but the only thought in my head after Freud finished was this: how could factitious be synonymous with fictitious}

Freud continued. 'Enough. For now the chief task is to discover the preexisting trauma that caused the girl's hysterical reaction on the roof. Tell me this: why didn't Nora tell the police where her parents were?'

I had asked myself the same thing. Miss Acton had told me that her parents were at George Banwell's country house, yet she had never mentioned this fact to the police, allowing them instead to send message after message to her own family's summer cottage, where no one was home. To me, however, this reticence was not mysterious. I have always envied those able to receive genuine comfort from their parents in times of crisis; there must be no comfort equal to it. But that was never my lot. 'Perhaps,' I answered Freud, 'she didn't care to have her parents nearby after the attack?'

'Perhaps,' he said. 'I concealed my worst self-doubts from my father for the whole of his lifetime. Like you.' Freud made the latter observation as if it were well known; in fact, I had not said a word about it to him. 'But there is always a neurotic ingredient in such concealment. Start on this point with Nora tomorrow, Younger. That is my advice. There is something in that country house. Undoubtedly it will be connected to the girl's unconscious desire for her father. I wonder.' He stopped walking and shut his eyes. A long moment passed. Then, opening his eyes, he said, 'I have it.'

'What?' I asked.

'Well, I have a suspicion, Younger, but I am not going to tell you what it is. I don't want to plant ideas in your head — or hers. Find out if she has a memory connected with this country house, a memory predating the episode on the roof. Remember, be opaque with her. You must be like a mirror, showing her nothing but what she shows you. Perhaps she saw something she should not have seen. She may not want to tell you. Don't let her off.'

On Tuesday, in the late afternoon, the Triumvirate were reassembled in the library. They had a great deal to discuss. One of the three gentlemen turned over, in his fine long hands, a report he had recently received and had shared with the others. The report included, among other things, a set of letters. 'These,' he said, 'we do not burn.'

'I told you: they are degenerates, all of them,' added the portly, ruddy-complexioned man next to him, with the muttonchop sideburns. 'We must wipe them out. One by one.'

'Oh, we will,' said the first. 'We are. But we will make use of them first.'

There was a brief silence. Then the third man, the balding one, spoke. 'What of the evidence?'

'There will be no evidence,' replied the first, 'except what we choose to leave behind.'

Detective Jimmy Littlemore exited the subway at Seventysecond Street and Broadway, the stop closest to the Balmoral. Mr Hugel might have his money on Banwell, but Littlemore hadn't given up on his own leads.

The evening before, when the Chinaman had disappeared, Littlemore had not been able to find out anything about him. The other laundry workers knew him as Chong, but that was all they knew about him. An assistant had told him to come back in the daytime and ask for Mayhew, the bookkeeper.

Littlemore found Mayhew recording figures in a back office. The detective asked the bookkeeper about the Chinaman who worked in the laundry.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Interpretation of Murder»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Interpretation of Murder» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Interpretation of Murder» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.