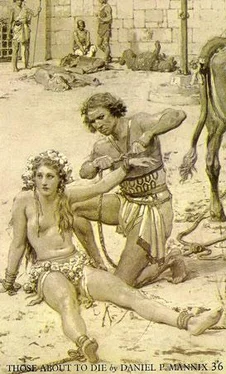

Daniel Mannix - Those About to Die

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Daniel Mannix - Those About to Die» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1972, ISBN: 1972, Издательство: Mayflower Books Ltd, Жанр: Исторические приключения, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Those About to Die

- Автор:

- Издательство:Mayflower Books Ltd

- Жанр:

- Год:1972

- ISBN:978-0583121347

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Those About to Die: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Those About to Die»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Those About to Die — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Those About to Die», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

On the day of the race, the city was almost deserted, nearly everyone being at the Circus Maximus. Troops had to patrol the empty streets to prevent looting by thieves. The races began at dawn and lasted until sunset. First there was a procession around the arena, led by the editor (the man giving the games), who was usually a politician running for office and needed votes. The editor rode in a chariot dressed in a purple toga as though he were a member of the nobility. Only as an editor of games could an ordinary man wear the purple. Around the chariot walked the editor's ward-heelers in white robes carrying palm branches, and after him rode a group of young aristocrats to show that men of wealth and breeding were also supporting the editor. Then came a long procession of priests carrying images of the gods on litters, swinging incense burners and chanting hymns. The crowd had been given handkerchiefs or placards with the editor's political slogan stamped on them ("Vote for Eprius Marcellus, the people's friend") and claques had been organised under cheer leaders to shout a slogan together. As the editor made the rounds, bowing and smiling, the claques all gave their cheers and the rest of the crowd stood up and waved the handkerchiefs or placards and shouted.

When the procession was over, the crowd sat down to study their racing forms and made last-minute bets with the bookies who ran up and down the aisles. Some of the forms, engraved on ivory or brass for the use of the nobility, are still in existence. They look like this:

1st Race

Racing Stable Team Colour of Horse Charioteer Stall Green Passerinus Grey Diocles III

Pomperanus Grey Tigris Chestnut

Raptore Black

And so on for all four teams in the first race.

Although the stalls from which the chariots started were all equidistant from a point midway between the stands and the end of the Spine, the charioteers who had the left-hand stall had an advantage, being able to go straight to the Spine and thus gaining the inside track. The stalls were numbered from one to four and charioteers picked their number out of a bowl. Diocles drew the third stall from the left.

Slaves were out watering the track to keep down dust, raking the sand and making sure no one had thrown any empty wine skins or gnawed bones on the track. A trumpet was blown and the track was hurriedly cleared. Meanwhile in the paddock behind the stalls the charioteers were getting their teams ready. The men wore short tunics that left their arms bare, heavy leather caps like crash-helmets, and each carried a knife in his belt so that in case of an accident he could cut himself free of the reins tied around his waist. Most of the drivers had coated themselves with boar's dung in the belief that the odour kept the horses from stepping on a man if he was thrown from his chariot.

The racing chariots were very light, made of wood with bronze fittings. They were lower and had a wider wheel base than the ordinary chariot. When the trumpet sounded to clear the track, teams were led out by their handlers and hitched up. There were several types of hitch used. Although the most usual was to have the two centre horses on either side of the shaft yoked together and the two outside horses on traces, sometimes a driver would have only his left-hand horse on traces. On rare occasions the entire team might be on traces to give them greater manoeuvrability. The horses' tails were always tied up so they wouldn't foul the reins.

The bitching-up must have been quite a sight—the horses pawing the ground and snorting, their manes studded with pearls and semi-precious stones. They wore breastplates hung with gold and silver amulets, and each horse had a broad ribbon the colour of his racing stable around his neck. The Romans claimed that chariot racing improved the breed of horses, but actually these animals were so inbred and temperamental that they were unfitted for anything except this breakneck dash around the arena at top speed.

Another trumpet sounded, the drivers took their places in the gleaming chariots and the grooms led the teams into the stalls, entering them from the rear. Then the grooms got out of the way—fast. A moment's pause. The editor of the games rose in his box and dropped a handkerchief. The gates of the four stalls were thrown open at the same instant and the chariots were off.

Every driver tried to reach the inside track around the Spine. As a result, there were usually so many crack-ups in this first wild rush that a special gate had to be constructed under the stands near the starting point where the arena attendants could drag out the smashed chariots, dead men and horses so they wouldn't block the course when the rest had circled the Spine and started the second lap. Sometimes the race never got going at all—all the chariots ending up in a pile at this point.

To solve this problem, a white rope called the Alba Linea was stretched from the Spine to the stands, just high enough to trip a galloping team of horses. A judge who was stationed in a box could drop this rope if he decided that it was a fair start. If the chariots didn't get away together or if there was too much jostling and fouling at the start, he left the rope up and then the race had to start over again.

This rope posed a very critical decision for the charioteers. If a driver went all out to reach the preferred inside track around the Spine and the rope wasn't dropped in time, he and his chariot went wheels over shaft. If he held back too much and the rope was dropped at the last instant, some other driver got ahead of him. It helped to know the judge's prejudices. If he was a secret supporter of the Blues and the Blue chariot was left at the post, he'd keep the rope up. If Blue was ahead, he'd drop the rope no matter what.

In this race, we'll suppose that all the chariots got away to an even start and the rope was dropped as the foremost chariot approached it. We can be pretty sure that this foremost chariot wasn't Diocles. He was famous for holding his team back until the last lap and then coming from behind to win. Diocles might even have been running last as the four chariots swept around the cones at the far end of the Spine on their first turn.

The basic strategy of all charioteering was to take the turns as tight as possible, but there were many other tricks. If ahead, you tried to block the others so they couldn't pass. If you were in the middle, you cut in front of the other chariots on the turns to force the drivers to rein in. If you got the chance, you hooked your wheel inside the wheel of an opposing chariot and then suddenly swung your team out.

If properly done, it could jerk your opponent's wheel off the axle and put him out of the race.

We'll suppose that by the end of the fifth lap, Orestes, a Greek driving for the Reds, is ahead of Diocles, driving for the Greens, just behind. Diocles is using his whip only on three of the horses, controlling Passerinus, his inside horse, by voice alone. Orestes is a skilful driver and as they go into the sixth lap, he manages to block Diocles on the turns so the Spaniard can't pass him. Then the two chariots level out for the rush down the lefthand side of the Spine. In spite of everything Orestes can do, Diocles pulls up alongside of him—but on the outside. They still have one more turn around the end of the Spine, and Orestes cuts it as close as he dares—Diocles turning with him.

As they spin around, Orestes slackens his reins too much while his team is making the swing. His axelrod hits one of the cones and breaks. Orestes is thrown out and as he falls, he tries to jerk out the knife in his belt to cut himself free of the reins. He can't get it free in time. Diocles has had to throw all his weight back on his reins to keep from being entangled in the wreck ahead for the pull of the dragging axle-bar has swung Orestes' team in front of him. Orestes is dragged along by his frantic horses; one moment he's half standing and then he's feet uppermost. The other two chariots following the leaders see their chance and try to pass, but Diocles shouts to his team and gives them their heads. They plow through the wreckage of Orestes' chariot, trampling the Greek underfoot. Passerinus trips and almost falls but Diocles grabs the stallion's reins in both hands and keeps his head up. Now they're through the wreckage and in the clear. One final burst of speed and they cross the finish line while the crowd goes wild. Orestes' corpse is so trampled that, as a contemporary writer remarked after the race, "His best friend couldn't have identified the body."

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Those About to Die»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Those About to Die» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Those About to Die» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.