12

Microcosm or Distorting Mirror? The Career of English

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

T. S. Eliot, ‘Little Gidding’ [649]

The career of the English language, like that of most of the world’s major languages, is often retold to its own speakers, and seldom without some element of triumph. The glories of any language community are hard for a speaker-patriot to resist, and few have any true conception of ages other than their own.

But even from the perspective of this book, there is still a sense in which the story of English deserves a special position among world languages. True, it happens to be the language with the widest spread in the era when these words are written. And in this era the world has become a single community linked by instant communications, making English uniquely prevalent, and leaving us wondering whether there could still be anywhere for a successor language to spring from. But the material fact for us is that English is a language with a remarkably varied history. This history is short: English as an identifiable language is no more than 1.5 millennia old, and its substance changed radically about halfway through its short life. But it has packed into this short span such a variety of crises and unpredictable outcomes that it can almost be seen as a personal summary of the adventures of its predecessors, all the way back to Memphis, Patna, Chang-an and Babylon.

One advantage of viewing English in the light of so many parallels is to reveal the essential strangeness of many developments that are usually taken for granted. We have already noted the success of Germanic Anglo-Saxons and Frisians in implanting their language, a striking feat when set against the achievement of other Germanic invaders, above all their contemporaries the Franks and the Goths settling in other parts of the western Roman empire. More than a thousand years later, the early English settlers in North America were spontaneously to establish a populous English-language community, while the French Crown was having to send out filles à marier to prevent the young settlers from going native and bringing up families without French. And a century after that, the activities of the English East India Company led to the spread of its own language, English, while the Dutch East India Company, over the same period, succeeded only in spreading a pre-existing lingua franca, Malay. These are just three of the cases where a certain kind of situation has contributed to the expansion of English, but has had no similar effect on other languages. The historic spread of a language is a hard thing to account for fully; but keeping a range of languages in mind may at least help us to escape some half-truths.

The history of English, at least as viewed from the beginning of the twenty-first century, falls into two very unequal periods: one of formation , from the fifth to the end of the sixteenth centuries, during which the language took shape, growing up in the island of Britain; and one of propagation , from the seventeenth century to the present, in which it took ship, spreading to every continent of the world.

We have already considered the beginning of the formation period, when, as part of the turmoil at the end of Rome’s empire, it coalesced from a group of Germanic dialects (see Chapter 7, ‘Against the odds: The advent of English’, p. 310). Despite political disunity and military threat, it had developed by the ninth century into a major literary language. Nevertheless, two centuries later, French-speaking conquerors were to stifle its written expression. Somehow, in the course of the next two centuries, it succeeded in assimilating the language community that was dominating it, to re-emerge as the foremost language of the realm. In the same period, it also spread geographically, establishing bridgeheads in every kingdom in the British Isles, among the Welsh, the Scots and the Irish. There was a further period of turmoil, in the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries, when the population was halved by the plague, the royal succession repeatedly disrupted by war, the Church shaken by protest and schism, and the currency racked by inflation. During all this time, English was spoken and written, but with no national standard uniting the various dialects. Linguistic stability came at much the same time as political stability, both focused on London, and mass readership of the Bible.

In the propagation period, when English speakers begin to travel and settle abroad, the temper of the English, and so by association their language too, becomes much more worldly, in both literal and figurative senses; the world is opened up to the English, but above all to their business and trading enterprise, with government and Church concerns very much in the rear. This idea of ‘English—the Businessman’s Friend’ may be what is really distinctive about the spread of this language, though equally distinctively reinforced by English-speaking science and technology. Certainly, this commercial and scientific character sets it apart from such major rivals as Spanish, French and Russian. It has become even more dominant in the very recent history of the twentieth century, when a single English-speaking ex-colony has become the world’s greatest power, competence in the language itself has become a major industry, and the spread of the language has accelerated well beyond the influence of the states that speak it natively. It is estimated that those who use English for convenience as a lingua franca now outnumber–by perhaps three to one—the total population of all native English speakers. Language prestige does not go much higher than this.

This apparent autonomy acquired by English means that, unlike most of the languages considered in this book, it is not yet possible to trace the beginnings of a downward trend in use of the language, even if the political and economic forces that put English up there have largely peaked. But we shall not be deterred. The life-histories of the many languages we have considered have shown various factors that can end the reign of a world language. It will be instructive to finish our account of English by using them to conjecture various paths downward from its present heights, unassailable as they appear.

Endurance test: Seeing off Norman French

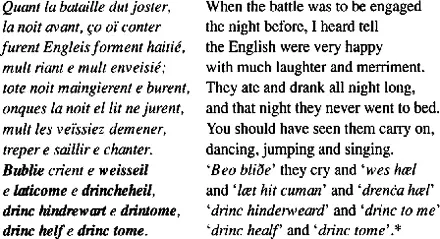

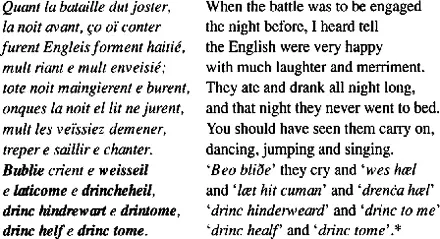

[857]

[857]

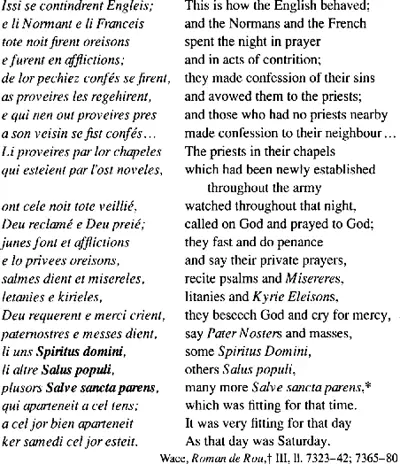

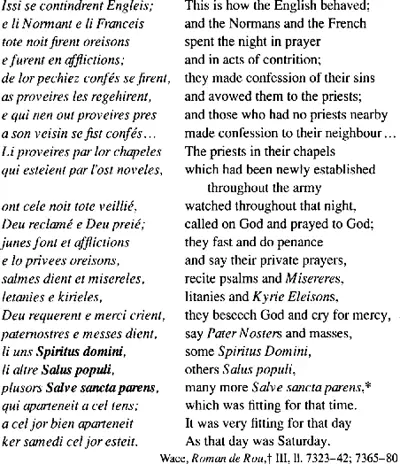

[858] [859]

[858] [859]

In a sense, the Norman conquest of England in the mid-eleventh century was an anachronism, the last of the Germanic invasions to convulse a European country, a couple of centuries too late. [176]

The Normans, after all, were only five or six generations away from their Norwegian ancestry as Vikings, and Normanni is just a Latinisation of NorδrTcross;menn , ‘north men’, which is still the word for Norwegians in Icelandic Norse. At the end of the ninth century, under their leader Rollo, they had been living by their swords, but they sailed south, and settled in what became Normandy, having coerced the Frankish king Charles III (the Simple) into granting them title, by the Treaty of St-Clair-sur-Epte, c .911. There they proceeded to put away their roving and marauding ways, including the Norse language; as typical Germanic invaders, in a couple of generations they had given up using their own language, and adopted the local Romance tongue, which on their lips is known as Norman French. When Rollo’s descendant, William the Bastard, led his successful invasion of England in 1066, he brought this language into England with him.

Читать дальше

[857]

[857] [858] [859]

[858] [859]