Meanwhile great events had shaken the German fatherland. It had sat out the Middle Ages under the alias of the ‘Holy Roman Empire’—in combination often with much of Italy, though without any loss of its German language—but when the Reformation came and the old structures disintegrated, Germany found itself vulnerable. In the seventeenth century the country was widely devastated by the Thirty Years War (1618-48), pitting Catholics against Protestants. But thereafter, although political stability and military security continued to elude them, German speakers were rewarded for their innovative seriousness—and later their Romanticism—with a golden age in science, the arts and all kinds of scholarship; and the German language and literature achieved world prominence, for the first time equalling French in international respect. The eighteenth century was the era of Lessing, Goethe and Schiller, Mozart and Beethoven, Herder and the brothers Humboldt, Kant and Hegel, ensuring that many of the key ideas of the Enlightenment (known to Germans as die Aufklärung ) were first expressed in German.

Since the breakdown of the Holy Roman Empire, German speakers in the south had remained relatively united in the kingdom of Austria ( Österreich —’the easterly kingdom’), ruled by the Habsburg dynasty. But in the nineteenth century, most of the Germans’ territories to the north of this were forcibly united under the strong, avowedly militarist leadership of Prussia, billing its creation as a renewed deutsches Reich , ‘German Empire’. As a nineteenth-century European power, this new Germany naturally felt that it needed colonies abroad: in short order, it took possession of four territories in Africa—Togoland, Cameroon, Southwest Africa (Namibia) and East Africa (Tanganyika)—in the 1880s, and north-east Papua and most of the Micronesian islands in the Pacific in the 1890s. All these new subjects of the Kaiser were just beginning to receive instruction in the German language when Germany emerged defeated from the First World War; at Versailles in 1919, the German language lost all its overseas territories, their administrations being switched to French, English and (in Micronesia) Japanese.

The expansive German spirit made a dramatic and desperate last throw in 1939, briefly imposing a new and greater Reich over most of the northern and central reaches of continental Europe from the Atlantic to the Urals; but the six years of totalen Krieg , ‘total war’, which made up the full period for which it was able to maintain its grip, were too short to show whether any linguistic gains for German were in train. Germany’s style of conquest of its European neighbours was certainly not adapted to win friends or admirers; but there would probably have been post-war settlements of Germans to the east, aimed at sweeping aside speakers of Slavonic languages, and perhaps German-based Creoles may have grown up among mixed populations in a vast network of forced labour camps. As it was, the politicians’ demented push for military glory ended up almost erasing the language influence that German had achieved in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In the 1930s, serious scientists, artists and intellectuals in every field, especially German-speaking Jews, left in droves for exile abroad—especially to the USA, where they became English speakers; and in the post-war era, the still-fresh Nazi associations of German discouraged much use of it outside its home countries.

Hitler’s painfully direct Drang nach Weltherrschaft , ‘drive for world domination’, was mercifully soon defeated; but culturally, it had already proved self-defeating. It will be interesting to see whether the German language can begin to enhance its prestige in the changed conditions of the twenty-first century, with Germany and Austria now playing leading roles as well-established democracies, at the centre of a Europe which is, nominally at least, seeking ‘ever closer union’.

Imperial epilogue: Kōminka

Kōminka:  The imperialization of subject peoples… Without this sense of profound gratitude for the limitless benevolence of the Emperor, provisional subjects cannot grasp the true meaning of what it is to be Japanese… While Kōminka as a concept may seem abstract and difficult to grasp, its fundamental principles are the same as those of the Imperial Rescript on Education; to understand one is to understand the other.

The imperialization of subject peoples… Without this sense of profound gratitude for the limitless benevolence of the Emperor, provisional subjects cannot grasp the true meaning of what it is to be Japanese… While Kōminka as a concept may seem abstract and difficult to grasp, its fundamental principles are the same as those of the Imperial Rescript on Education; to understand one is to understand the other.

Washisu Atsuya, Recollections of Government in Taiwan , Taipei, 1943, p. 339

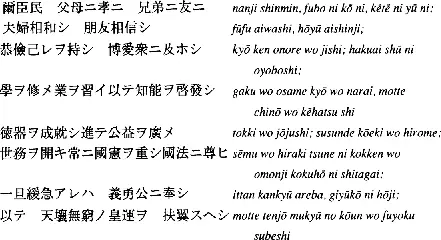

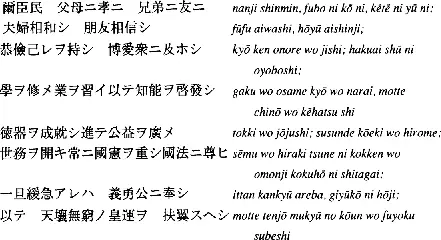

Ye subjects, be filial to your parents, affectionate to your brothers and sisters; as husbands and wives be harmonious, as friends true; bear

yourselves in modesty and moderation; extend your benevolence to all; pursue learning and cultivate arts, and thereby develop intellectual faculties and perfect moral powers; voluntarily promote common interests;

embarking on public affairs always respect the Constitution and observe the laws;

in case emergency arises, serve courageously; and thus aid the prosperity of the Imperial Throne eternal as heaven and earth.

From the Kyōiku ni kansuru Chokugo

(Imperial Rescript on Education) of 30 October 1890, displayed in all Japanese schools, beside the portrait of the emperor

We have to establish a new, European-style empire on the edge of Asia.

Inoue Kaoru, Japanese foreign minister, 1887 [645]

Japan is evidently no European power. But the motive with which it won for itself an overseas empire was of European inspiration. And viewed as a sequel to European empire-building, the brief story of this venture displays much of the causation, the methods and ultimate vanity of this type of language spread.

Japan had been a strictly isolationist state until visited in 1853 by the American Commodore Perry’s ‘Black Ships’; by 1858, it had been forced to conclude trade treaties with the major European powers. The traditional rule of the Tokugawa shogun was then unsettled in a number of violent incidents, which impressed some Japanese with the military power of the foreigners, especially the British navy. In 1868, shouting such slogans as  son nō jō i , ‘honour emperor; expel barbarians’, and

son nō jō i , ‘honour emperor; expel barbarians’, and  fu koku kyō hei , ‘rich country; strong army’, [172]these radicals overthrew the feudally based government that had lasted for the previous two and a half centuries, and established a new, radically Westernising, regime under the nominal supervision of the young Emperor Meiji, who had conveniently come to the throne in 1867. Expeditions were dispatched to Europe and the USA to find out how they were organised. By 1889 Japan had adopted a new constitution, with two houses of parliament (one hereditary and another elected by wealthy householders), centrally appointed prefectural governors, an army general staff directly responsible to the emperor (and hence immune from civilian control), and a national civil service, police force, banking and educational system. Within a single generation, Japan had put itself on a par with the leading Western powers, and proceeded to demonstrate its independence.

fu koku kyō hei , ‘rich country; strong army’, [172]these radicals overthrew the feudally based government that had lasted for the previous two and a half centuries, and established a new, radically Westernising, regime under the nominal supervision of the young Emperor Meiji, who had conveniently come to the throne in 1867. Expeditions were dispatched to Europe and the USA to find out how they were organised. By 1889 Japan had adopted a new constitution, with two houses of parliament (one hereditary and another elected by wealthy householders), centrally appointed prefectural governors, an army general staff directly responsible to the emperor (and hence immune from civilian control), and a national civil service, police force, banking and educational system. Within a single generation, Japan had put itself on a par with the leading Western powers, and proceeded to demonstrate its independence.

The main strategic motive for Japan’s colonial wars was Korea. Japan was taking lessons in geopolitics from the West; and Major Meckel, the German adviser to the Imperial Army, had characterised Korea as ‘a dagger thrust at the heart of Japan’, thinking of its value to a hostile power. Dispossessed samurai, the ancient class of knights who were the main losers in Japan’s modernisation, had almost drummed up an outright invasion of the country early in the 1870s. But in 1894 China was invited into Korea to help subdue a rebellion, and Japan—citing a treaty right to ensure Korea’s neutrality—came too. The Japanese started throwing their weight about, kidnapping the Korean king and queen to make their point; and Chinese resistance proved not only futile but costly. In the settlement of the war in 1895, China was forced to cede the islands of Taiwan and the Pescadores to Japan: these became Japan’s first colony.

Читать дальше

The imperialization of subject peoples… Without this sense of profound gratitude for the limitless benevolence of the Emperor, provisional subjects cannot grasp the true meaning of what it is to be Japanese… While Kōminka as a concept may seem abstract and difficult to grasp, its fundamental principles are the same as those of the Imperial Rescript on Education; to understand one is to understand the other.

The imperialization of subject peoples… Without this sense of profound gratitude for the limitless benevolence of the Emperor, provisional subjects cannot grasp the true meaning of what it is to be Japanese… While Kōminka as a concept may seem abstract and difficult to grasp, its fundamental principles are the same as those of the Imperial Rescript on Education; to understand one is to understand the other.

son nō jō i , ‘honour emperor; expel barbarians’, and

son nō jō i , ‘honour emperor; expel barbarians’, and  fu koku kyō hei , ‘rich country; strong army’, [172]these radicals overthrew the feudally based government that had lasted for the previous two and a half centuries, and established a new, radically Westernising, regime under the nominal supervision of the young Emperor Meiji, who had conveniently come to the throne in 1867. Expeditions were dispatched to Europe and the USA to find out how they were organised. By 1889 Japan had adopted a new constitution, with two houses of parliament (one hereditary and another elected by wealthy householders), centrally appointed prefectural governors, an army general staff directly responsible to the emperor (and hence immune from civilian control), and a national civil service, police force, banking and educational system. Within a single generation, Japan had put itself on a par with the leading Western powers, and proceeded to demonstrate its independence.

fu koku kyō hei , ‘rich country; strong army’, [172]these radicals overthrew the feudally based government that had lasted for the previous two and a half centuries, and established a new, radically Westernising, regime under the nominal supervision of the young Emperor Meiji, who had conveniently come to the throne in 1867. Expeditions were dispatched to Europe and the USA to find out how they were organised. By 1889 Japan had adopted a new constitution, with two houses of parliament (one hereditary and another elected by wealthy householders), centrally appointed prefectural governors, an army general staff directly responsible to the emperor (and hence immune from civilian control), and a national civil service, police force, banking and educational system. Within a single generation, Japan had put itself on a par with the leading Western powers, and proceeded to demonstrate its independence.