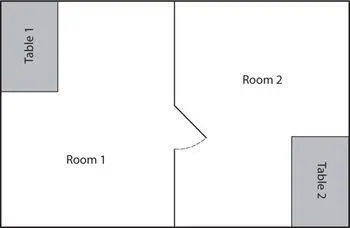

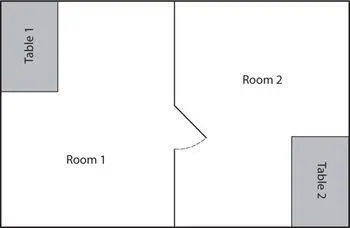

Does all this mean that we and speakers of Guugu Yimithirr sometimes remember “the same reality” differently? The answer must be yes, at least to the extent that two realities that for us can look identical will appear different to them. We, who generally ignore rotations, will perceive two arrangements that differ only by rotation as the same reality, but they, who cannot ignore rotations, will perceive them as two different realities. One way of visualizing this is to imagine the following situation. Suppose you are traveling with a Guugu Yimithirr friend and are staying in a large chain-style hotel, with corridor upon corridor of identical-looking doors. Your room is number 1264, and your friend is staying in the room just opposite yours, 1263. When you go to your friend’s room, you see an exact copy of yours: the same little corridor with a bathroom on the left as you enter, the same mirrored wardrobe on the right, then the main room with the same bed on the left, the same indistinct-brown curtains drawn behind it, the same elongated desk next to the wall on the right, the same television set on the left corner of the desk and the same telephone and minibar on the right. In short, you have seen the same room twice. But when your Guugu Yimithirr friend comes into your room, he will see a room that is quite different from his, one where everything is reversed. Since the rooms face each other (rather like rooms 1 and 2 in the picture shown here), and since they have been arranged to look the same from the egocentric perspective, they are actually north-side-south. In his room the bed was in the north, in yours it is in the south; the telephone that in his room was in the west is now in the east. So while you will see and remember the same room twice, the Guugu Yimithirr speaker will see and remember two different rooms.

CORRELATION OR CAUSATION?

One of the most tempting and most common of all logical fallacies is to jump from correlation to causation: to assume that just because two facts correlate, one of them was the cause of the other. To reduce this kind of logic ad absurdum, I could advance the brilliant new theory that language can affect your hair color. In particular, I claim that speaking Swedish makes your hair go blond and speaking Italian makes your hair go dark. My proof? People who speak Swedish tend to have blond hair. People who speak Italian tend to have dark hair. QED. Against this epitome of tight logical reasoning you may come up with a few petty objections along these lines: Yes, your facts about the correlation between language and hair color are perfectly correct. But couldn’t it be something other than language that caused the Swedes to have blond hair and the Italians dark? What about genes, for instance, or climate?

Now, as far as language and spatial thinking go, the only thing we have actually established is correlation between two facts: the first is that different languages rely on different coordinate systems; the second is that speakers of these languages perceive and remember space in different ways. Of course, my implication all along was that there is more than just correlation here and that the mother tongue is an important factor in causing the patterns of spatial memory and orientation. But how can we be sure that the correlation here is not as spurious as that between language and hair color? After all, it is not as if language itself can directly create a sense of orientation in anyone. We may not know exactly what clues the Guugu Yimithirr rely on for telling where north is, but we can be absolutely certain that their remarkable surety about directions could have been achieved only through observation of cues from the physical environment.

Nevertheless, the argument advanced here is that a language like Guugu Yimithirr indirectly brings about the sense of orientation and geographic memory, because the convention of communicating only in geographic coordinates compels the speakers to be aware of directions all the time, forcing them to pay constant attention to the relevant environmental clues and to develop an accurate memory of their own changing orientation. John Haviland estimates that as many as one word in ten (!) in a normal Guugu Yimithirr conversation is north, south, west, or east, often accompanied by very precise hand gestures. Put another way, everyday communication in Guugu Yimithirr provides the most intense drilling in geographic orientation from the earliest imaginable age. If you have to know your bearings to understand the simplest things people say around you, you will develop the habit of calculating and remembering the cardinal directions at every second of your life. And as this habit of mind will be inculcated almost from infancy, it will soon become second nature, effortless and unconscious.

The causal link between language and spatial thinking thus seems far more plausible than the case of language and hair color. Still, plausibility by no means constitutes proof. And as it happens, some psychologists and linguists, such as Peggy Li, Lila Gleitman, and Steven Pinker, have challenged the claim that it is primarily language that influences spatial memory and orientation. In The Stuff of Thought , Pinker argues that people develop their spatial thinking for reasons unrelated to language, and that languages merely reflect the fact that their speakers think in a certain coordinate system anyway. He points out that it is small rural societies that rely primarily on geographic coordinates, whereas all large urban societies rely predominantly on egocentric coordinates. From this undeniable fact he concludes that the system of coordinates used in a language is determined directly by the physical environment: if you live in a city you will spend much of your time indoors, and even when you venture outside, turning right and then left and then left again after the traffic lights will be the easiest way of orienting yourself, so the environment will encourage you to think primarily in egocentric coordinates. Your language will then simply reflect the fact that you think in the egocentric system anyway. On the other hand, if you are a nomad in the Australian bush, there are no roads or second left turnings after the traffic lights to guide you, so egocentric directions will be far less useful and you will naturally come to think in geographic coordinates. The way you then end up speaking about space will just be a symptom of the way you think anyway.

What is more, says Pinker, the environment determines not just the choice between egocentric and geographic coordinates but even the particular type of geographic coordinates that will be used in a language. It is surely not a coincidence that the Tzeltal system relies on a prominent geographic landmark, whereas the Guugu Yimithirr system uses compass directions. The environment of Tzeltal speakers is dominated by a visible landmark, the uphill-downhill slope, and so it is only natural for them to depend on this axis rather than on the more elusive compass directions. But as the environment of the Guugu Yimithirr lacks such prominent landmarks, it is no wonder that their axes are based on compass directions. In short, Pinker claims that the environment has decreed for us what coordinates we think in, and it is spatial thinking that determines spatial language, not vice versa.

While Pinker’s facts are hardly quibbleable with, his environmental determinism is unconvincing for several reasons. It makes sense, of course, that each culture would home in on a coordinate system suitable for its environment. Still, it is crucial to realize that different cultures have a considerable degree of freedom. For example, there is nothing in the physical environment of the Guugu Yimithirr that precludes their using both geographic coordinates (for large-scale space) and egocentric coordinates (for small-scale). There is no conceivable reason why a traditional hunter-gatherer existence would prevent anyone from saying “there is an ant in front of your foot” instead of “to the north of your foot.” After all, as a description of small-scale spatial relations, “in front of your foot” is just as sensible and just as useful in the Australian bush as it is inside an office in London or Manhattan. This is not merely a theoretical argument-there are various languages of societies similar to Guugu Yimithirr that indeed use both egocentric and geographic coordinates. Even in Australia itself, there are aboriginal languages, such as Jaminjung in the Northern Territory, that do not rely only on geographic coordinates. So Guugu Yimithirr’s exclusive use of geographic coordinates was not directly imposed by the physical environment or by the hunter-gatherer way of life. It is a cultural convention. The categorical refusal of Guugu Yimithirr ants ever to crawl “in front of” Guugu Yimithirr feet is not a decree of nature but an expression of cultural choice.

Читать дальше