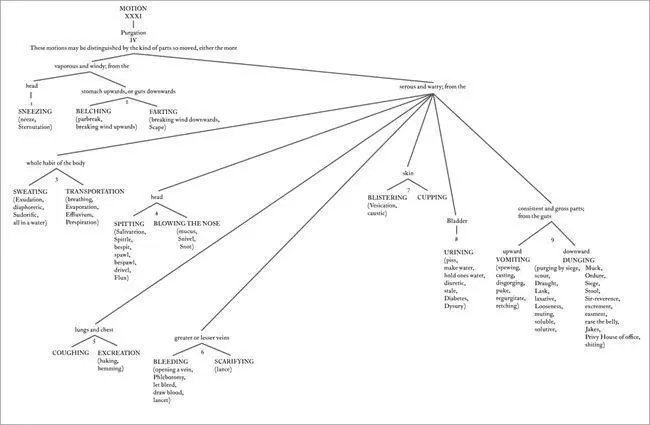

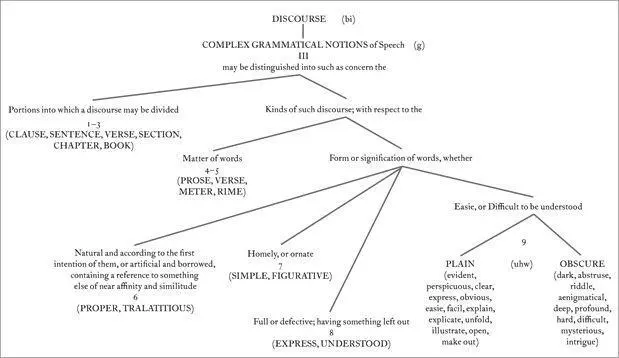

Figure 6.1: Category XXXI (Motion), subcategory IV (Purgation)

Sexual matters being a bit above my level of dictionary maturity, I continued my search in the next category, number XXXI, “Motion.” After skimming past the first three subcategories (animal progression, modes of going, and motions of the parts), which rather haphazardly encompassed everything from “swimming” to “ambling” to “yawning,” I came to subcategory IV, purgation, where I found: “Those kinds of Actions whereby several animals do cast off such excremetitious parts as are offensive to nature.” This was a seven-year-old boy’s dream catalog of bodily function, and it bears reproducing in its entirety (see figure 6.1).

What a window on the past! How interesting to note that people once talked of “breaking wind upwards,” or that you could just as well “neeze” as sneeze. How much less distant three hundred years ago seems when one realizes that then, too, people said “snot” and “puke.” And there it was, not just “shiting,” but a fascinating array of alternatives, which, being the scholar that I am (immaturity notwithstanding), sent me to the Oxford English Dictionary to look for origins and explanations.

“Muting,” for example, is a special word for “bird poop.” And “sir-reverence” used to mean “with all due respect” (from the Latin salva reverentia —“save [your] reverence”). People usually pull out “with all due respect” when they are about to drop some bad news, so I suppose the change of meaning came about after enough people, upon hearing the phrase, thought to themselves, “Oh, great. Here comes another pile of sir-reverence.”

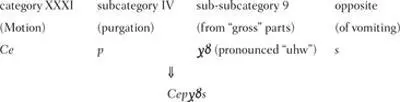

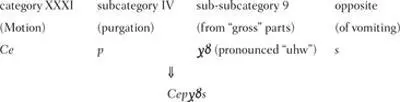

Once I had located my target concept in the tables, I could finally piece together the word for it:

Cepuhws . A serous and watery purgative motion from the consistent and gross parts (from the guts downward). That’s how you say “shit” in Wilkins’s language. By the time I figured it out, I was too tired to giggle.

Knowing What You Mean to Say

Even though Wilkins’s universe was supposed to be a more organized, rational place than the one I was living in, I sometimes found it disorienting. Animals could be categorized according to the shapes of their heads, their eating preferences, or their general dispositions. I didn’t really understand why emotions were classified as simple (hope) or mixed (shame), or why tactile sensations could be active (coldness) or passive (clamminess). Entertaining was a bodily action, but shitting was a motion—so was playing dice. While things as different as irony and semicolon were grouped together (under discourse > elements), things as similar as milk and butter were placed miles apart (milk with the other bodily fluids in “Parts, General,” and butter with other foodstuffs in “Provisions”).

There is an absurdity to Wilkins’s categorization of the universe that was best highlighted in an article by Borges titled “The Analytical Language of John Wilkins”:

These ambiguities, redundancies and deficiencies remind us of those which doctor Franz Kuhn attributes to a certain Chinese encyclopedia entitled “Celestial Empire of benevolent Knowledge.” In its remote pages it is written that the animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) suckling pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies.

Borges’s point is not to ridicule Wilkins’s attempt to impose a pattern on the universe (he later concedes that Wilkins’s is “not the least admirable of such patterns”), but to call attention to the hopelessness of all such attempts.

“It is clear,” he says, “that there is no classification of the universe not being arbitrary and full of conjectures. The reason for this is very simple: we do not know what thing the universe is.”

I thought it would be appropriate, in a slyly ironic way, to attempt a translation of these lines into Wilkins’s language.

This translation was no simple matter. The sentiment expressed in these lines is quite correct. In Wilkins’s tables I found arbitrariness and conjecture all around. He did not know (as we do not) what thing the universe is. But he took a heroic stab at it. Over the four days I worked on my translation, sly irony gave way to surprised admiration. As a language of its own, Wilkins’s work was unusable, but as a study of meaning in English it was brilliant.

I started by looking up the word for “clear.” Where, in the universe of ideas, might this one fall? What does “clear” mean, in the grand scheme of things? Well, lots of things. In the index I found over twenty-five options listed. Do you mean “not mingled with another”? Then see “simple.” Do you mean “visible”? Then see “bright,” “transparent,” or “unspotted.” Do you mean “as refers to men”? Then see “candid.” Do you mean “not hindered from being passed through”? See “accessible” or “empty.” Do you mean in the sense of “clear weather”? That would be El.VI.1 (elements > condition of the air > being transparent). “Not guilty”? That’s RJ.II.6 (relations, judicial > concerning proceedings > decision regarding party’s lack of transgression).

Near the end of the list I found the particular sense of “clear” that I was after: “not hindered from being known.” This entry referred me to two possibilities, “plain” or “manifest.”

So I turned to the entry for “plain.” It referred me to many senses I could reject—“simple,” “mean,” “homely,” “frank,” “flat-lands”—but two offerings seemed promising: “not obscure” and, once again, “manifest.” I was hovering over the right meaning area now, re-spotting landmarks and getting oriented.

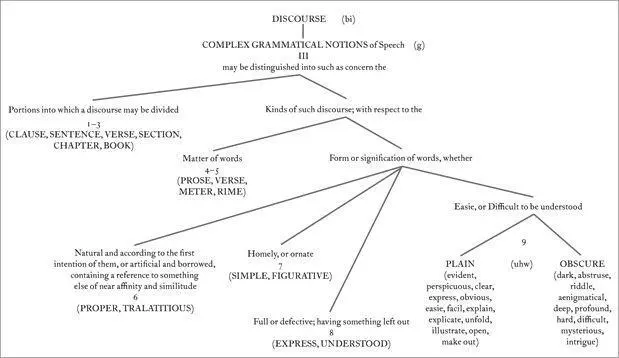

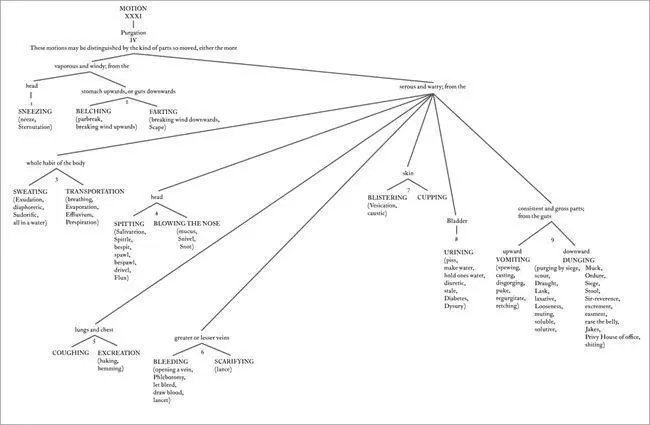

“Not obscure” was located in the tables at D.III.9 (discourse > complex grammatical notions > concerning the form or signification of words, with regard to their understandability). Figure 7.1 shows that section of the table (presented with the first eight sub-subcategories condensed).

Here, as in the table of bodily functions provided in chapter 6, words are followed by a list of synonyms. Wilkins considered synonymy to be one of the defects of natural language—a rational language should be free from redundancy; it should have one word for one meaning. A particular position in his table of concepts would be represented by a single word, and he intended all of the synonyms listed along with it to be covered under the same word. For example, the word for position 9, big  (pronounced “biguhw,” D = bi , III = g , 9 = uhw ) would be used for this particular sense of “plain,” as well as for the synonyms that follow it—“evident,” “perspicuous,” “clear,” “express,” “obvious.”

(pronounced “biguhw,” D = bi , III = g , 9 = uhw ) would be used for this particular sense of “plain,” as well as for the synonyms that follow it—“evident,” “perspicuous,” “clear,” “express,” “obvious.”

Читать дальше

(pronounced “biguhw,” D = bi , III = g , 9 = uhw ) would be used for this particular sense of “plain,” as well as for the synonyms that follow it—“evident,” “perspicuous,” “clear,” “express,” “obvious.”

(pronounced “biguhw,” D = bi , III = g , 9 = uhw ) would be used for this particular sense of “plain,” as well as for the synonyms that follow it—“evident,” “perspicuous,” “clear,” “express,” “obvious.”