I wondered if any of those who thought they could do better than Wilkins ever tried their hand at a “practical application” of his system. It is easy to take issue with his tables or his grammatical apparatus or his general view of the universe. You barely have to look at any of these things before you can find something to criticize. But if you sit down and make a sincere attempt to use the language, you discover the really important flaw, not in his language, but in the whole idea of a philosophical language: when you speak in concepts, it’s too damn hard to say anything.

People find something very comforting about the notion that words are the problem, not concepts. When words fail us, we tend to blame the words. We’ve all experienced the frustration of not being able to say what we mean to say. When we struggle with language, we have the sensation that our clean, beautiful ideas remain trapped inside our heads. We accuse language of being too crude and clumsy to adequately express our thoughts. But perhaps we flatter ourselves.

Sometimes we do find the words to express an idea, and only then realize what a stupid idea it is. This experience would suggest that our thoughts are not as clean and beautiful as we would like to believe. Instead of blaming language for failing to capture our thoughts, maybe we should thank it for giving some shape to the muddle in our heads.

I’m no philosopher, and I am not qualified to make claims about whether thought is possible without language (although I think it is), or whether there may be other means than language by which we can give shape to the muddle (sure, why not?). I’m just saying that when it comes to expressing ourselves, we need some fuzzy edges, a chance to discover what we’re trying to say even as we say it. We should be grateful to our sloppy, imperfect languages for giving us some wiggle room.

To be fair, Wilkins didn’t assume our thoughts were as organized as his language. But he did assume there was a truth “out there” that his language could help us to see “by unmasking many wild errors, that shelter themselves under the disguise of affected phrases.” His system would help us learn to think clearly. To know the word would be to know the thing. We would be able to see everything for what it was. And if we suspected something wasn’t what it seemed, we could call it what it was—the serous and watery purgative motion (from the guts downward) of the consistent and gross parts of a male, hollow-horned, ruminant, cloven-footed beast.

The “language as mathematics” idea, as we will see, had a resurgence in the late 1950s, another era of science and computation. It would be used as a tool of inquiry and experiment, a way to discover how language might work, how our minds might work.

But the goals of the seventeenth-century language inventors went beyond that. They were after a cure for Babel. They wanted a real, working language that people could use. They neglected, however, to think much about usability.

Except for poor George Dalgarno. Remember him? The stubborn schoolmaster whose disagreements with Wilkins had resulted in the end of their collaboration? He wanted to keep the number of root words in his language to a minimum. He wanted them organized in verses that were easy to memorize. Wilkins pushed for philosophical perfection. Dalgarno pushed back for usability. They came to an impasse.

Dalgarno left Oxford for a few months to work alone. He returned to find that scholarly interest was now solely focused on Wilkins’s emerging project. His own work was ignored or undermined by accusations that he was plagiarizing from Wilkins. In his disappointment he resolved to “make haste to cast it lyke an abortive out of my hands.”

But instead, “after bemoaning myself and my unfortunate labors I made all haste possible.” He worked frantically, hoping to beat Wilkins to publication. In his anxiousness, his confidence faltered. He reorganized his root words, doing away with the mnemonic verses and replacing them with a hierarchical table of the type Wilkins had argued for. His list of root words grew. But he clung to his principles by presenting a method to aid memorization (a sort of word-association strategy that he doesn’t elaborate on very much), and he was sure to emphasize that he did not provide root words for the enormous range of natural species (like he knew Wilkins would). He instead promoted his compounding strategy (for example, elephant = largest whole-footed beast; coal = mineral black fire).

Dalgarno managed to publish Ars signorum (The Art of Signs) in 1661, seven years before Wilkins’s Philosophical Language came out. His rush to publication went unrewarded. The one detailed review he received mocks him for his poor skills in Latin, implies that his benefactors supported him only because they felt sorry for him, and concludes by using his own language to call him nηkpim sυfa (the greatest ass).

Because of Dalgarno’s haste and his obvious discomfort with some of the Wilkins-influenced features he had decided to adopt, Ars signorum was, in fact, kind of a mess. And a great deal harder to figure out how to use than Wilkins’s system ultimately was. But Dalgarno deserves credit for having been unique in at least thinking about the usability of his language in practical terms. The other language inventors of the time had their heads in the philosophical clouds. They assumed that if you got your theory of concepts right, the language would automatically be easy to learn and to use. Dalgarno, ever the teacher, gave a little more consideration to the poor soul at the other end of that assumption. And in doing so, he was a very early pioneer of the next major era in language invention.

Ludwik Zamenhof and the Language of Peace

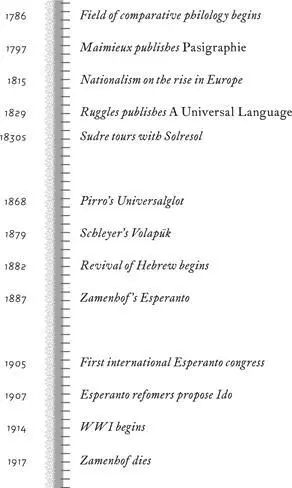

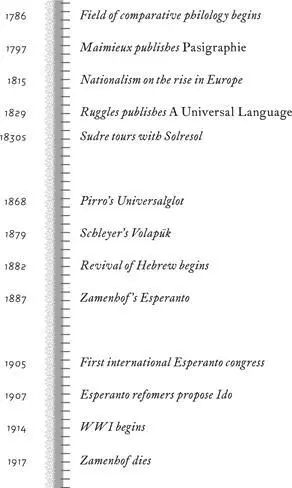

By the time Wilkins, Dalgarno, and the rest of the intellectual circle of the philosophical language inventors were dead, French had become the international language of culture and diplomacy. Scientific academies in Berlin, St. Petersburg, and Turin adopted French as an official language. Treaties were drafted in French, even when neither party was a French-speaking nation. The elites of all European nations could conduct their business in French. Scientists and philosophers no longer focused their attention on creating a new universal language—they had one that worked well enough.

Language projects cropped up here and there, of course, especially after the work of Leibniz came into fashion among scholars in the 1760s. French was fine for communication purposes, but it was no perfect mathematical system. A couple of projects attempted to make French a bit more orderly, while others continued the tradition of starting from scratch with letters, numbers, and symbols in the quest for that perfect system. One of these, the Pasigraphie of Joseph de Maimieux, gained a bit of success—for a few years around 1800, it was taught in schools in France and Germany, and Napoleon was reported to have admired it. But probably only in theory. Had he actually tried to use it, his assessment may have been different. He would have found himself lost in a thicket of tables, sub-tables, columns, and lines, all serving to carve up the world of experience into arbitrary categories, all filled with odd-looking symbols that were hard to distinguish from each other.

Читать дальше