Dalgarno’s system provided a list of 935 “radicals”—the primitive concepts he judged necessary for effective communication— and a method for writing them. They were not, however, organized into a hierarchical tree. They were not grouped by shared properties, or by any logical or philosophical system. Instead, they were placed into a verse composed of stanzas of seven lines each, so that they could be easily memorized. For example, if you memorize the first stanza, you know the placement of forty-two of his radical words (italicized):

When I sit-down upon a hie place , I’m sick with light and heat

For the many thick moistures , doe open wide my Emptie pores

But when sit upon a strong borrowed Horse, I ride and run most swiftly

Therefore if I can purchase this courtesie with civilitie , I care not the hirers barbaritie

Because I’m perswaded they are wild villains, scornfully deceiving modest men

Neverthelesse I allowe their frequent wrongs and will encourage them with obliging exhortations

Moreover I’l assist them to fight against robbers , when I have my long crooked sword.

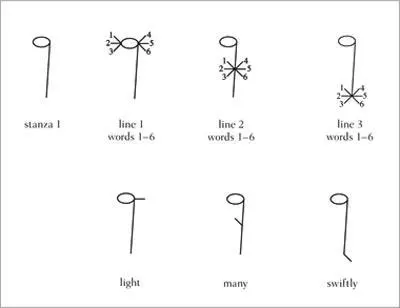

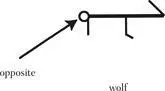

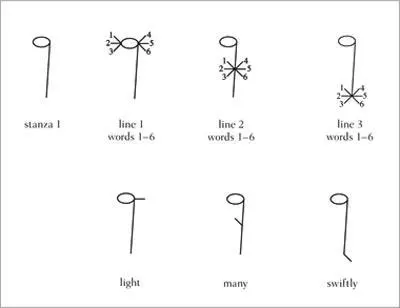

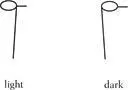

He developed a written character where the placement and direction of little lines and hooks referred to a specific place in a line of a stanza (as shown in figure 5.4).

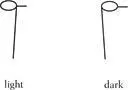

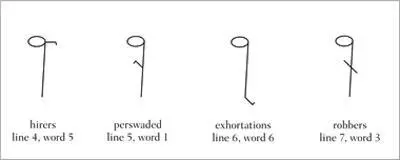

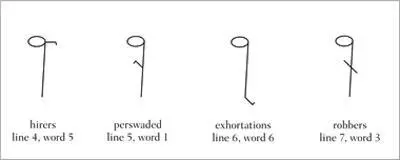

To write “light,” for example, you draw the character representing the first stanza modified by a small mark indicating first line, fifth word. The pattern is repeated for the fourth through sixth lines, but with little hooks added to the marks, and for the seventh line the mark is drawn through the character (as shown in figure 5.5).

Figure 5.4: Dalgarno’s system

Additionally, the opposite of a word was represented by reversing the orientation of the stanza symbol.

He also provided for a way for the system to be spoken by assigning consonants and vowels to the numbered stanzas, lines, and words. So if B = stanza 1, A = line 1, and G = word 5, then the word for “light” would be BAG .

Figure 5.5: Dalgarno’s system, lines 4–7

Wilkins admired Dalgarno’s system, but he thought it needed to include more concepts, and took it upon himself to draw up an ordered table of plants, animals, and minerals. Dalgarno respectfully declined to use those tables, arguing that the longer the list of concepts got, the harder they would be to memorize. He thought that specific species, like elephant, didn’t need their own, separate radical words, but that they could be referred to by writing out compound phrases, such as “largest whole-footed beast.”

Dalgarno’s method was another way to get a mathematics of language. No need to determine a universe of categories and distinguishing features—you simply decide what the primitives are (no need to systematically break everything down; just ask yourself what makes sense) and assume everything else can be described by adding those primitives together to make a compound. For Dalgarno, “coal” is “mineral black fire,” “diamond” is “precious stone hard,” and “ash tree” is “very fruitless tree long kernel.”

Wilkins thought this method lacked rigor. Dalgarno hadn’t chosen his basic concepts in a principled way, and, worse, the words in his language told you nothing about their meanings, just their arbitrary placement in a nonsense verse. Wilkins was convinced that the ordered tables were necessary. He wanted words to reflect the nature of things—only in this way could the language serve as an instrument for the spread of knowledge and reason. Dalgarno thought the tables were unnecessary. He wanted words to be easy to memorize—only in this way could the language be a useful communication tool. After about a year of arguing, they parted ways, and Wilkins began to work on his own project.

The problem with natural languages, as Wilkins saw it, was that words tell you nothing about the things they refer to. You must simply learn that a dog is a “dog” in English or a chien in French or a perro in Spanish or a Hund in German. The sounds in those words are just sounds to be arbitrarily memorized. They tell you what to call a dog, but they do not tell you what a dog is.

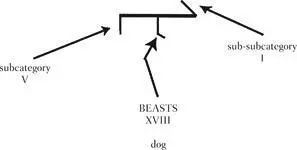

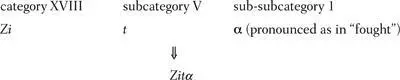

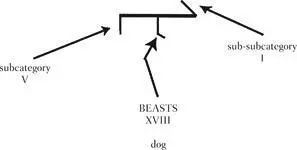

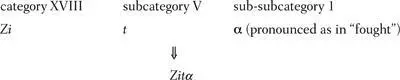

In Wilkins’s system, the word for “dog” does tell you what a dog is. Like Dalgarno, Wilkins worked out a way to refer to a specific position in his tables with a character or a word. Since the concept dog is located in category XVIII (Beasts), subcategory V (oblong-headed), sub-subcategory 1 (bigger kind) (refer to figure 5.3), the character for “dog” would be formed with the symbol for category XVIII, along with modifications indicating subcategory V, and sub-subcategory 1.

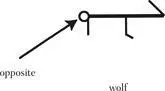

The character for “wolf,” being paired with “dog” on the basis of a minimal opposition (docile versus not docile), requires an additional marking for opposite.

Wilkins’s scheme for forming pronounceable words follows the same plan. “Dog” is zitα :

and “wolf” is zitαs .

The words of both Dalgarno’s and Wilkins’s systems direct you to a position in a table, but only in Wilkins’s case does that position mean something. Dalgarno’s word for “light,” BAG , shows you where in his verses the word “light” may be found (stanza 1, line 1, word 5), but it does not tell you what light is. Zitα , on the other hand, gives you a definition of a dog: a clawed, rapacious, oblong-headed, land-dwelling beast of docile disposition.

A word in Wilkins’s language doesn’t stand for a concept; it defines the concept. So, to return to the important business at hand, what is the definition of “shit”? Where might I find it in Wilkins’s tree of the universe? Wilkins does provide an index to his tables, where you can look up specific English words and find out where they fall in the hierarchy. If you look up, say, “rabble,” you will find written next to it RC.I.7 (relations, civil > political relations of rank > of the lower sort, in the aggregate). Sometimes the word directs you to another word; if you look up “parsimony,” it will tell you to see “frugality” (which then directs you to Man. III.3—manners > virtues relating to our estates and dignities > in regards to keeping as opposed to getting). But “shit” doesn’t appear in the index, nor does “feces.” So I set out to find it by figuring out its true definition. To begin, I turned to what seemed to be the most promising category for my quest, number XXX, “Corporeal Action.” But I did not find what I was looking for. The concepts included in this category ranged from quite general (living, dying) to quite specific (itching, stuttering). I noted that some of them, contrary to the indications of their category title, didn’t seem very corporeal (editing, printing) or very action-like (dreaming, entertaining). But this category did include the concept politely known as coition, listed along with a colorful collection of synonyms: “coupling,” “gendering,” “lie with,” “know carnally,” “copulation,” “rutting,” “tread,” “venery.” The word for all this, by the way, is cadod (a corporeal action > belonging to sensate beings > of the kind concerning appetites and the satisfying of them > relating to the preservation of the individual > as regards the desire of the propagation of the species).

Читать дальше