Let’s cut to the chase and get the words down on the page. American comedian George Carlin was the first to list the Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television in a radio monologue in 1972. He reckoned they were: shit, piss, fuck, cunt, cocksucker, motherfucker and tits . ‘Those are the heavy seven. Those are the ones that’ll infect your soul, curve your spine and keep the country from winning the war.’

According to linguist Steven Pinker there are five swearing distinctions: dysphemistic ( I have to take a shit ); abusive ( Fuck you! ); idiomatic ( I was pretty fucked up last night ); emphatic ( I’m not going to do a fucking thing ); and cathartic ( Fuck, I’ve spilt my coffee! ).

The fact is, lots of us swear. It’s become part of everyday life for more and more people, especially those under the age of thirty. People who count such things estimate we swear anything between fourteen and ninety times a day and half the times we use fuck and shit . So should we be bothered that it’s now okay to repeat these most offensive of oaths on air and in print without retribution? Was Oscar Wilde right when he said, ‘The expletive is a refuge of the semiliterate’? Or did Shakespeare get it right when he wrote: ‘But words are words. I never did hear / That the bruised heart was pierced through the ear’? Is there such a thing as good or bad language, and is it advisable, or even possible, to control it?

Taboo or not taboo, that is the question.

The word taboo derives from the Tongan word tabu , meaning ‘set apart’ or ‘forbidden’, and was first used in English back in 1777 by the explorer Captain James Cook. After observing the eating habits of the people of the South Pacific islands, he wrote:

Not one of them would sit down, or eat a bit of any thing … On expressing my surprise at this, they were all taboo, as they said; which word has a very comprehensive meaning; but, in general, signifies that a thing is forbidden … When any thing is forbidden to be eaten, or made use of, they say, that it is taboo.

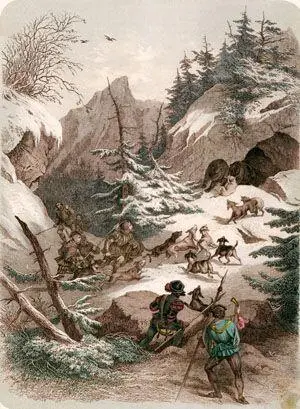

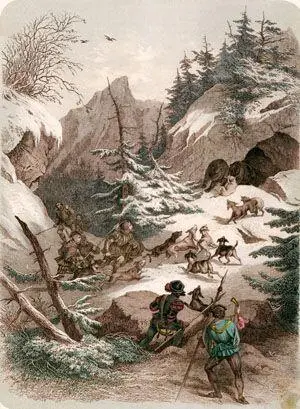

Hunters with their dogs corner a bear in its cave: the first taboo

And so taboo entered the English language, meaning something forbidden. Taboo subjects in almost all societies tend to involve religion, sex, death and bodily functions; things that frighten us or make us uneasy. The first taboo word in the Proto-Indo-European language was apparently for the animal we call the bear. It was so ferocious, so feared that people were scared to give it a name. It was referred to as the honey-eater or the licker or the brown one ( bruin in Old English, from which we get bear).

Societies have developed a raft of words and expressions to deal with taboo subjects in contrasting ways: either to avoid mentioning the taboo subjects at all or deliberately to use the taboo words to inflame, to hurt, offend and shock. Sometimes it’s simply for emotional release.

Take the subject of death. Given that it’s the only certain thing in life (apart from, perhaps, taxes), we’re remarkably coy about using the d-word. Instead, we say he’s passed away, passed on, given up the ghost, gone to meet his maker, shuffled off this mortal coil or joined the choir invisible ; we use euphemisms (from the Greek word meaning ‘use of good words’) to sweeten the harsh reality. If we want to laugh at death or be brazen about it, we use dysphemisms (Greek for ‘non-word’). He’s croaked, pegged out, pushing up the daisies, bitten the dust, popped his clogs, cashed in his chips, kicked the bucket, called it quits or (quite awful) taking a dirt nap .

We do the same for bodily functions. We fart, break wind, pass gas, let rip, toot, poot, pop, parp or trumpet ; rather than defecate, we poo or do a number two, have a shit or a dump, shed a load, test the plumbing or — if you’re in the medical profession — have a bowel movement . As for urinating, our replacement expressions are endless: we pee, piddle, piss, slash, wee, widdle, have a jimmy riddle, go for a tinkle, take a leak, spend a penny, strain the potatoes, water the garden/tulips/tomatoes , and, if you’re a man, point Percy at the porcelain or shake hands with an old friend .

There’s a lovely expression: to mince one’s words, to mince meaning to soften or moderate. The way society has got round the problem of using outright profanities is to express a minced oath. We take a four-letter expletive, add a bit of rhyme or alliteration and come up with a softer, inoffensive version. Flipping, frigging, fecking, sugar, shoot and shucks — so innocent-sounding and yet so not. And if you thought you were being mild calling someone a berk instead of an idiot, think again: it’s from the rhyming slang ‘Berkeley Hunt’.

In our more pious past, words were altered to avoid blasphemy. Some of the euphemisms — zounds (God’s wounds), gadzooks (meaning God’s hooks, perhaps from the nails of the cross) and God’s bodkins (God’s body) — have fallen out of use. But our language today is still littered with expressions originally used to avoid taking God’s name in vain. We say good gracious, golly, gosh, by gum, begorrah, strewth (God’s truth) or cor blimey (God blind me). We make a detour round Christ or Jesus by uttering cripes, crikey, for crying out loud (for Christ’s sake), gee, jeepers or Jiminy Cricket (did anyone tell Walt Disney?). Instead of hell and damn, we say heck and darn or darnation, dang or doggone . And what the Dickens! isn’t alluding to the author but substituting the devil with a minced oath.

Professor Timothy Jay is a naughty words expert (what a great line to put in your CV). He’s a psychologist at Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts and for the past thirty years he’s been studying the role of dirty words in linguistics. Jay himself was exposed to swearing from an early age. His father was a carpenter, and the young Timothy would visit him at work on the building sites. ‘I would hear things. The carpenters were planing a piece of wood, and the guy would say, “Take a few more cunt hairs off of that,” or “I gotta cut that tit off there.” So I would hear this language. If these guys came over to the house and they were with their families, you wouldn’t hear any of it. But on the job — constant.’

Professor Jay calls swear words emotional intensifiers . ‘It’s like using the horn on your car, which can be used to signify a number of emotions,’ he says. ‘Like anger, frustration, joy or surprise.’

Swearing is so deeply rooted in the brain — both literally and metaphorically — that it stays with us longer. Jay claims that children learn swear words at a very early age and also learn the taboos that society places on them. ‘As soon as kids can speak, they’re using swear words,’ says Jay. ‘That doesn’t mean they know what adults know, but they do repeat the words they hear.’ His team’s research revealed that children learn and use swear words as young as two or three. Because they’re learned so early, they’re deeply ingrained and like nursery rhymes are retained longer than other language forms.

Children learn that swear words are powerful; they often hear them during arguments when people’s emotions are running high, and when the child repeats the word, they get an emotional response. It’s the emotional link of swear words that gives them their psychological potency. Anything that is forbidden is powerful.

Читать дальше