Ross’s article was published in an obscure Finnish academic journal and might have passed unnoticed if it hadn’t been read by the unabashedly U author Nancy Mitford. She immediately penned an article entitled ‘The English Aristocracy’, in which she expanded on the U and non-U theme and added a few of her own suggestions to a glossary of terms used by the upper classes. The essay provoked a debate about English class consciousness and snobbery. Mitford’s article was reprinted along with contributions from Evelyn Waugh, John Betjeman and others in Noblesse Oblige . Betjeman had a jolly good dig at the upwardly aspiring middle classes in his poem ‘How to Get on in Society’, which opens with the line ‘Phone for the fish knives, Norman’.

Professor Ross asked the burning question ‘Can a non-U-speaker become a U-speaker?’ to which he answered no: ‘in these matters, U-speakers have ears to hear so that one single pronunciation, word, or phrase will suffice to brand an apparent U-speaker as originally non-U’.

In fact, as Professor Ross, Nancy Mitford and Co. were discoursing social language, England’s tight class system was already beginning to loosen. As the distinction blurred, so too did the boundaries between accents. What’s interesting about the lists of U words is that today most of them have been adopted by everyone else.

The most famous purveyor of U-speak today is the Queen, but even Her Majesty’s accent is showing signs of change. An Australian study of the Christmas broadcasts from the 1950s to the 1980s suggests that the Queen too is becoming less posh. Her vowels, apparently, have flattened slightly over the years, moving towards the modern standard accent of southern England. In the 1950s, her pronunciation of the word had almost rhymed with bed , and the words pat, mat and man sounded like pet, met and men . Today her accent is more like that of a posh Radio 4 announcer.

So if the accent of the U-class has become much more a standard RP, what of the non-U? Well, apart from RP and local accents, the accent for the non-U of the south-east of England is developing into a so-called Estuary English — somewhere between RP and Cockney. In EE, the th sound is becoming f or v; t s are dropping at the ends of words and the final l s in words are sounding like w s. EE, it’s said, is less posh than RP but not as working-class as Cockney. In its strongest form it’s the ‘Am I bovvered?’ accent of Catherine Tate’s comic character or the ‘yoof’ drawl of journalist Janet Street Porter. Tony Blair is supposed to have adopted a mild form of Estuary English as prime minister when he wanted to appeal to Joe Public.

We’re in a call centre in Newcastle, one of the boom industries of the twenty-first century. Over a million Britons are employed by companies as telephone agents to deal with customer inquiries or travel bookings or a myriad of other transactions. In this industry, regional accents — most of them, anyway — are prized possessions, and some are gold dust. Survey after survey puts Yorkshire and Geordie accents high on the warm, friendly and ‘pleasing to the ear’ scale. A Scottish accent gets top rating for most trustworthy; Welsh and Irish score highly as well. (Some accents don’t fare so well: poor old Liverpudlian Scouse and Birmingham Brummie languish at the bottom as the most unappealing accents in Britain.)

The Newcastle call centre manager, Lawrence Fenley, explains that his employees are proud of their Geordie accent.

‘Why should they hide it? Everybody in this centre is very proud of where they’re from and their heritage. They will speak to the customers the way that they do to their friends, and it goes down very, very well.’

Clearly we humans have an emotional need to latch on to language; if you can’t see the face of the person you’re talking to, then the next best thing is their accent, because somehow we feel it’s an expression of their character, their cultural belonging. Something like a Geordie accent has a very particular quality.

Brand consultant James Hammond makes this very point.

‘In the twenty-first century things have changed an awful lot in terms of how we understand, appreciate and fit in with accents. And what we’ve got now is a society which is much more into an emotional connection. And, therefore, this Received Pronunciation, this Queen’s English, is deemed almost condescending to us. We want accents that are much more personable … and we’ve got a celebrity status society now. So people like Ant and Dec and Cheryl Cole have really brought something like the Geordie accent to the fore.’

James does point out that RP is still the accent of choice when people want to speak to someone in authority.

‘It is only when, usually, you have an issue, a problem, where that needs to be escalated up to somebody in a superior position, a manager or whatever, that you then expect a certain kind of accent. And, funnily enough, we then revert back to the Queen’s English, because people feel more comfortable with that.’

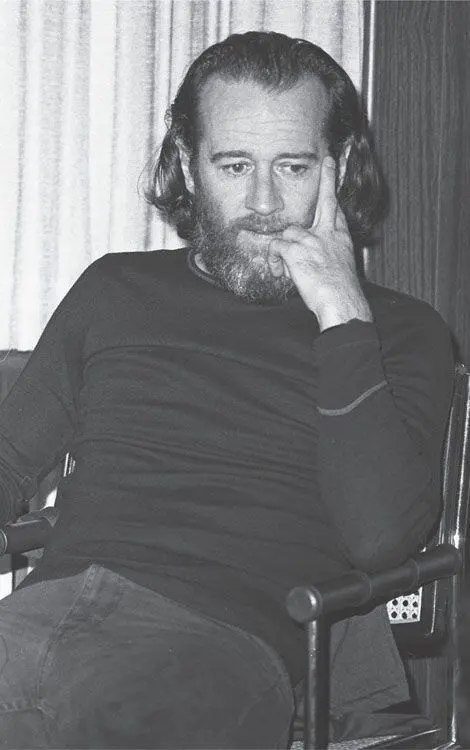

Ant and Dec helping develop our love affair with the Geordie accent

Until relatively recently people thought having a posh accent was the key to success in life; that you’d be trusted and believed if you spoke like that. It’s just not the case any more.

Yorkshireman Wilfred Pickles would have been delighted. As he wrote in his autobiography in 1949: ‘May it be forbidden that we should ever speak like BBC announcers, for our rich contrast of voices is a local tapestry of great beauty and incalculable value, handed down to us by our forefathers.’

The last word must go to Barnsley poet Ian McMillan, a man who believes he is defined by his language and accent.

‘Barnsley’s what I think with. I think with its history, I think with its culture, I think with its hills that you walk up and get out of breath, I think with its wind that stops me talking in big words, big, big mouth openings. So yes, I think in the end, no matter how I try to write on the page, it will always come out with Barnsley’.

Language is the most versatile of tools, far exceeding the uses for which it was first designed. We humans probably began to talk to each other about the best places to hunt or which plants to avoid eating as a means of survival, but the way we use words has evolved into something much more complex. Our language can be playful and shocking and witty and dangerous. It allows us to express our anger verbally rather than physically, with expletives, and to profane the sacred or confront taboos; we hide behind the language of doublespeak to conceal truths, and cover our embarrassment with euphemisms; groups create secret codes for their protection or disguise or uniqueness; professions develop their own language for efficiency and accuracy; sometimes we use language simply to cover up the fact that we haven’t a clue what we’re talking about.

Like all complex tools, language can go wrong. It’s when words erupt from us wildly, uncontrollably or don’t come at all that we are given tiny insights into the mystery of how language works.

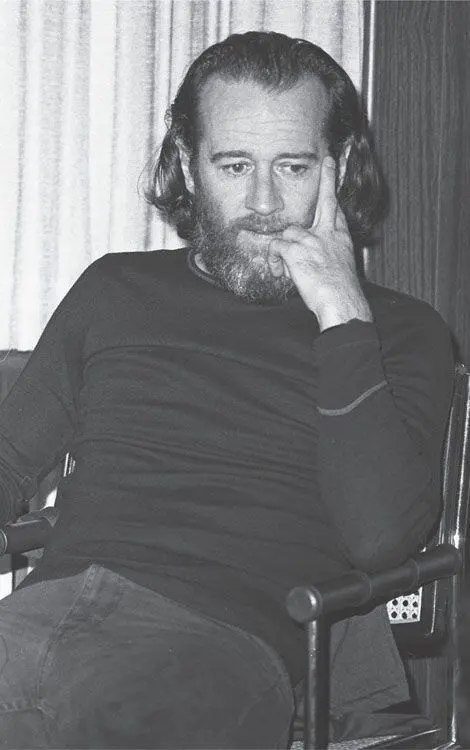

George Carlin backstage, March 1976, Pittsburgh

Those of you with a sensitive disposition might like to skip the next few pages, for this is a chapter about bad language — whether it’s jargon, slang, terms of abuse or, of course, swear words. If you choose to read on, be warned. The most offensive words in the English language are about to get an airing.

Читать дальше