Barnsley poet Ian McMillan lives and breathes Yorkshire and is a collector of local words, some of which can be pinned down to a single town or village. One word, lenerky , which means ‘soft’ or ‘floppy’, is found only in the tiny village of Grange Moor in West Yorkshire. There are some glorious words like bartled, to be smothered in something nasty, or plotter for mud or gloppened for astounded.

Ian says he speaks Barnsley rather than Yorkshire because within the dialect there are a huge range of accents, often changing from one village to another. He illustrates his point with a map of Yorkshire and shows how, in the space of just a few miles, the Yorkshire accent changes. His finger traces a journey from Hull in the east to Leeds (‘long e s and very slow’) and Bradford (‘they don’t say their t s’) and then down to Barnsley (‘harsh … it’s to do with the harsh winds of Yorkshire; you don’t want to open your mouth too far’). Ian’s finger hovers over the A61 as it makes its way down towards Sheffield. ‘That’s where an isogloss happens, where language changes over a small space. The th hardens to a d . So you start off from Barnsley, going “now then, now then”, and as you approach Sheffield your vowels will be going “nar den, nar den”. We call Sheffield people deedars , for the way they change the th in thee and thou to d .’

By the time Ian’s finger stops its linguistic travels at the border with north Derbyshire, we’ve entered a foreign land. ‘My Aunty Mabel, who was from Chesterfield, would say things like “I’ve just had double glazing fitted in my arse.” Or she’d say, “I’ve got a detached arse.” ’ Somewhere in the twenty-odd miles from Barnsley to Chesterfield, along the invisible isogloss line, house had changed to hears then to harse and ended up as arse .

Like all dialects, Yorkshire Tyke bears history. The traces of all the people who’ve come and gone and the work they did — it’s all there in the layers of speech, says Ian, often without us knowing.

‘Whenever I speak in my voice, behind me, in a huge line, are standing all the people who ever spoke like me. So that when I’m walking through Barnsley and somebody shouts to a lad, “Come on, clarteead, frame thissen!” you think, wow, that’s a term from down the pit.’

Ian explains that a clout was a kind of nail used in the coal mines. Clout head or clarteead means ‘idiot’. And frame thissen has Old English roots meaning ‘get on with it!’

‘So, somehow, the language carries on, using specific industrial terms that have gone, and they just hang on, like a kind of cloud or a ghost language … When the word dies, then the memory of a way of life will go as well. When a word isn’t spoken any more then the roots of that word wither away.’

Ian remembers being told at school not to speak with his broad Yorkshire accent if he wanted to get on in life. ‘And when I was first on the radio, a Barnsley listener rang up and said, “Tha’ can’t talk like that on’t wireless.” I said, “But I talk just like you.” And he said, “Ar, but tha’ can’t talk like it on’t wireless. They’ll think tha’re common!” ’

A generation or so ago, speaking in anything other than Received Pronunciation — the Queen’s English — was regarded as a social disadvantage. The ideal was to speak in a way that revealed nothing about your background, your class or where you’d been to school. As the elocutionist Arthur Burrell wrote in 1891: ‘It is the business of educated people to speak so that no-one may be able to tell in what county their childhood was passed.’

RP developed from what was an essentially regional accent in the south-east of England. When William Caxton set up England’s first printing press in 1473, he chose, largely, the spelling and pronunciation of the South-east/Midlands dialect as Standard English, as that was the most populous region of England and home to the royal court at London.

With the entrenching of the class system during the Industrial Revolution, the regional working-class accent increasingly branded the speaker as socially inferior. The development of public boarding schools like Eton and Rugby in the nineteenth century helped establish the RP accent as the ‘standard’ voice of the English gentleman, who went out into the world to build empires and occupied the highest positions in Victorian society.

The launch of the British Broadcasting Corporation in 1922 confirmed the place of Received Pronunciation as the accent of educated, middle-class England. Its first Director General, John Reith, said, ‘One hears the most appalling travesties of vowel pronunciation. This is a matter in which broadcasting can be of immense assistance … We have made a special effort to secure in our various stations men who … can be relied upon to employ the correct pronunciation of the English tongue.’

RP became so synonymous with the dinner-jacket-wearing radio announcers that it came to be known as BBC English. This is what we would call today ultra posh, the sort of English spoken only by members of the royal family and the upper classes.

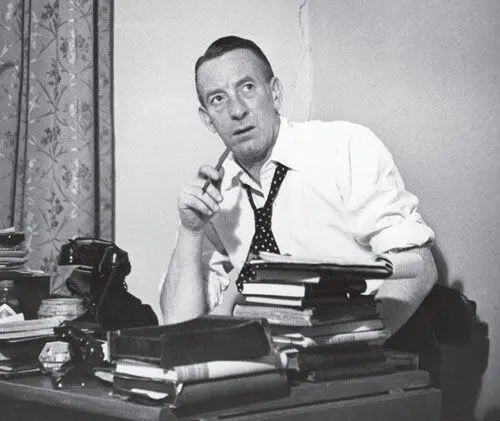

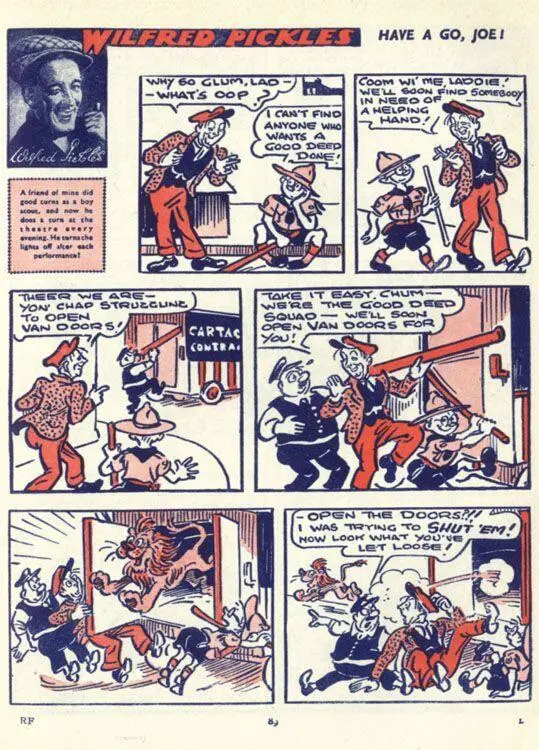

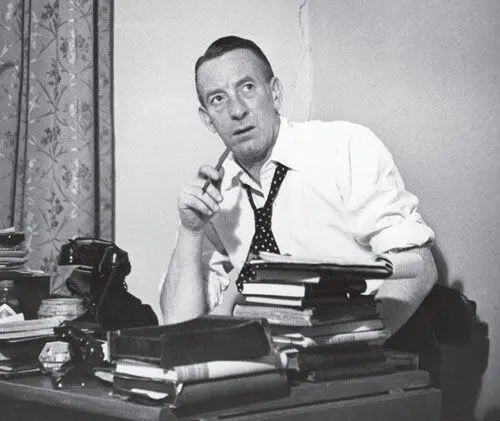

Yorkshireman and BBC broadcaster, Wilfred Pickles

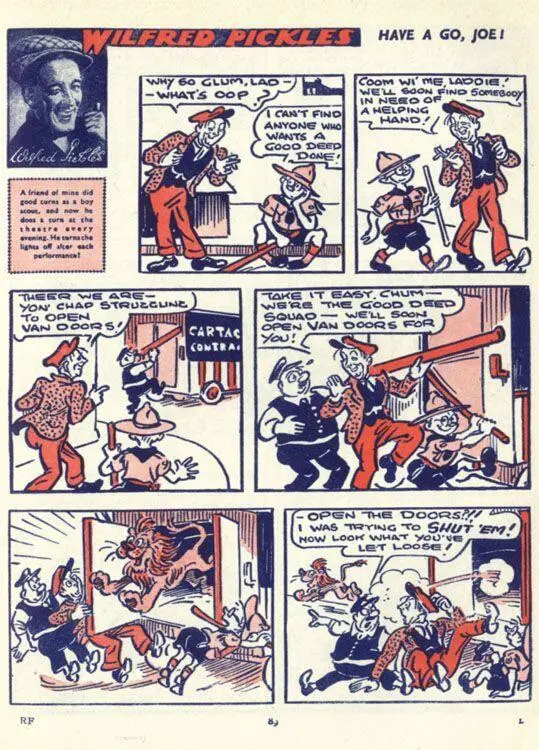

Wilfred Pickles rolls up his sleeves …

The BBC did in fact break with tradition during the Second World War, when it hired a Yorkshireman, Wilfred Pickles, as a radio news announcer. They thought that if the Nazis invaded Britain and infiltrated the BBC broadcasts, they’d find it more difficult to impersonate a regional accent. Radio announcers had already begun introducing themselves by name at the beginning of wartime news bulletins to ensure that listeners ‘be able to recognize instantly the authentic voice of BBC broadcasting’. Wilfred Pickles’ news broadcasts caused a furore, although if you listen to the BBC sound archives, it’s rather hard to understand what all the fuss was about; you have to concentrate quite hard to distinguish the Yorkshire burr. Pickles did, however, infuriate southern listeners by ending the midnight bulletin with ‘And to all in the North, good neet.’ London cartoonists took their revenge by drawing him with rolled-up shirtsleeves and wearing a cloth cap.

Queen Elizabeth II in 1952, making her first of many Christmas radio broadcasts

‘It is impossible for an Englishman to open his mouth without making some other Englishman hate or despise him,’ wrote Irishman George Bernard Shaw in the preface to Pygmalion in 1916. Forty years later, the English were still obsessing about the social classes and their accents. Linguist Professor Alan Ross coined the expression ‘U and Non-U’ in 1954 to differentiate between the English upper classes (U) and the aspiring middle classes (non-U). He argued that members of the upper class weren’t necessarily better-educated, cleaner or richer than anyone else; the only thing which demarcated them was language (apart perhaps from ‘having one’s cards engraved … not playing tennis in braces and … dislike of certain comparatively modern inventions such as the telephone, the cinema and the wireless’). Do you have a bath (U) or take a bath (non-U)? Is your midday meal lunch (U) or dinner (non-U)? Do you wipe your mouth with a table napkin (U) or a serviette (non-U)? And do you use lavatory paper (U) or toilet paper (non-U)? Talking about greens instead of vegetables was very non-U, as was home instead of house and glasses rather than spectacles .

Читать дальше