Another astonishing correspondence concerns the attraction of Bears to human menstrual blood, a widespread belief in many Native American tribes. Implausible as this connection may sound, zoologists decided to conduct experiments to see if there was any truth to these “superstitions.” Employing controlled olfactory-preference tests on Polar Bears in both laboratory and field settings, they found that the animals were indeed significantly more attracted to the odors in human menstrual blood than to a number of other smells, including several animal and food odors as well as nonmenstrual blood. In fact, human menstrual odors in many cases elicited a response from the Bears as strong as that prompted by the smell of seals (their primary food in the wild), which they could detect from more than 1,200 feet away. 47

Even more extraordinary, biologists have found actual cases of physical gender-mixing in Bears. In 1986, Canadian zoologist Marc Cattet made a stunning discovery: the presence of significant numbers of “masculinized females” in wild populations of Grizzly, Black, and Polar Bears. These animals have the internal reproductive anatomy of a female combined with portions of the external genitalia of a male, including “penislike” organs. As many as 10–20 percent of the Bears in some populations may exhibit this phenomenon. 48Such individuals are able to reproduce, and most adult intersexual Bears are actually mothers that successfully raise cubs. In fact, the reproductive canal in some intersexual Bears extends through the phallus rather than forming a vagina, so that the female actually mates and gives birth through the tip of her “penis”—similar to the way female Spotted Hyenas mate and give birth through their “penile” clitoris. These findings offer striking parallels to the gender-mixing Bear Mother figure of many Native American tribes, as well as the Bimin-Kuskusmin and Inuit beliefs about “male mothers” and androgynous animals that give birth through a penis-clitoris.

Intersexual animals that combine male and female sex organs (and in some cases that are intermediate between males and females in their body proportions and size) also occur spontaneously in other mammals that are not usually hermaphroditic, such as primates (e.g., Common Chimpanzees, Rhesus Macaques, Savanna Baboons), whales and dolphins (e.g., Bowhead and Beluga Whales, Striped Dolphins), marsupials (e.g., Eastern Gray and Red Kangaroos, various Wallabies, Tasmanian Devils), and rodents and insectivores (e.g., moles). 49In fact, a veritable profusion of different kinds of gender mixing has been uncovered throughout the animal world—so much so that scientists have had to develop a special terminology to refer to the bewildering variety of intersexualities. Fanciful-sounding names such as chimeras, freemartins, mosaics, and gynandromorphs are actually the technical terms used by biologists to designate animals with various types of chromosomal and anatomical gender mixing. 50In Greek mythology, a chimera is a fantastic creature combining features of a lion, goat, and serpent, while Hermaphroditus is the child of the gods Hermes and Aphrodite. It is ironic that Western science uses names with mythological connotations to refer to animals that are actually the living “proof” of indigenous myths about homosexual and transgendered species. The left-handed androgynous Bear may exhibit chimerism (scientifically speaking), but it isn’t “chimerical” at all—it’s alive and well and living in North America!

A freemartin is an animal that becomes intersexual as a result of association in the womb (or egg) with a twin of the opposite sex (note the motif of twinning in some Native American two-spirit traditions that involve animals, such as the Kamia and Wintu), while chimera refers to an animal with organs that combine genetically male and female elements. Similar to chimerism, a mosaic is an individual that has variable chromosomal patterns and a corresponding mixture of male and female traits. Some of the diverse types of chromosome configurations (in addition to the “typical” female and male patterns of XX and XY, respectively) include XXY, XXX, XXYY, XO, and even combinations of these in different cells of the body. Each chromosomal pattern, in turn, manifests itself as a different mixture of male and female sex organs and secondary sexual characteristics, sometimes juxtaposed in separate parts of the body, sometimes combined in the same organ, and sometimes blending together as a gradation of traits or a combination of all of these. 51

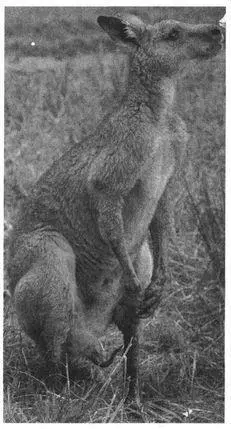

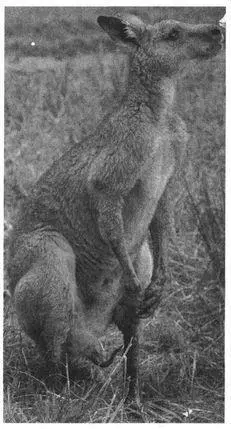

Myth made real: a transgendered (intersexual) Eastern Gray Kangaroo. This animal has both a penis and a pouch (the latter usually found only in females). Chromosomally, it combines the female pattern (XX) with the male (XY) to yield an XXY pattern.

One particularly remarkable type of mosaic is called a gynandromorph: an animal that appears to be literally divided in half, one side (usually the right) male in appearance, the other side female, often with a sharp line of demarcation between them. This occurs in a number of different kinds of animals, such as butterflies, spiders, and small mammals, and bears a noteworthy resemblance to the Bimin-Kuskusmin belief about a centipede that is female on its left side and male on its right. More than 40 cases of gynandromorphism have also been reported in birds such as finches, falcons, and pheasants. In these cases the two halves of the creature differ in plumage (and sometimes even size), usually corresponding to internal reproductive organs of both sexes (an ovary on one side, a testis on the other). Some gynandromorphs have more of a gender mixture in their appearance while still preserving a central dividing line. One warbler, for example, had a left side that was male while its right side was a tapestry of male and female plumage characteristics. Although little information is available on the behavior of gynandromorphs, it appears that some individuals may exhibit a combination of both male and female behavior patterns. One spider gynandromorph, for example, courted and mated with females using its male organs, but also built an egg case as is typical for females. On the other hand, a gynandromorphic chimney swift exhibited primarily (heterosexual) “male” behavior throughout its life, regularly pairing with females and fathering offspring. 52

Other examples of the correspondences between indigenous views about transgendered animals and scientific observations can be found. Sambia (and other New Guinean) beliefs about all-female offspring, gender mixing, and sex change in marsupials and other animals may seem far-fetched, yet recent discoveries by zoologists studying a variety of species bear remarkable similarities to these ideas. For example, geneticists recently determined that significant numbers of female wood lemmings are actually chromosomally male (having an XY pattern). Moreover, some of these animals only give birth to female offspring, so that the population consists of 80 percent females. Similar phenomena occur in at least 7 other species of rodents, and individual females that only produce female offspring have also been reported as a recurring phenomenon in at least 12 different species of butterflies. 53True transsexuality is most often found in fishes (and “lower” animals), where the combination of sex change with chronological color change in some coral reef species echoes Sambia beliefs about sequential sex and plumage changes in birds (and other creatures). Cases of chromosomal “sex reversal” (males that have a female chromosomal pattern, or vice versa) occasionally occur in mammals such as moles, mole-voles, and primates (e.g., Orang-utans and Hanuman Langurs). 54And while Inuit beliefs about gender-mixing Caribou that wear female garments are not literally true, female Caribou often exhibit physical “transvestism” in the sense that they bear antlers (a trait typically associated with males in all other species of Deer).

Читать дальше