Finally, in some animals dominance and mounting are entirely separate, with social rank being expressed through obviously nonsexual activities. For example, male Walrus dominance interactions involve fighting and tusk displays that usually occur during the breeding season and often involve younger animals. Male homosexual mounting is not associated with either of these activities and usually takes place in the nonbreeding season among males of all age groups (a similar pattern is also seen in Gray Seals). Oystercatchers use a special ritualized “piping display” (neck arched, bill pointed downward, accompanied by shrill piping notes) to negotiate their dominance interactions, while same-sex mounting and courtship occur in other contexts. 87Dominance in many other animals is expressed through fighting and aggressive encounters, access to food or feeding frequency, body size or age, physical displacement (causing another individual to move off through posture, threats, staring, or other activities), access to heterosexual mating opportunities, or a combination of these or other factors, and specifically does not involve mounting or the other homosexual interactions that occur in these species. Savanna (Yellow) Baboons, (female) Hamadryas Baboons, Bottlenose Dolphins, Killer Whales, Caribou, Blackbucks, Wolves, Bush Dogs, Spotted Hyenas, Grizzly Bears, Black Bears, Red-necked Wallabies, Canada Geese, Scottish Crossbills, Black-billed Magpies, Jackdaws, Acorn Woodpeckers, and Galahs are all species in which this is the case. 88

Another limitation in looking at homosexual interactions from the perspective of dominance is that only mounting behavior lends itself to such an interpretation. A whole host of other homosexual activities do not fit neatly into the dominance paradigm—either because, by their very nature, they are reciprocal activities, or because neither participant can be assigned a clearly “dominant” or “subordinate” status on the basis of what “position” it assumes during the activity. For example, mutual genital rubbing—in which two animals rub their genitals on each other without any penetration—often occurs with neither participant “mounting” the other. Gibbon and Bonobo males frequently engage in this activity when hanging suspended from a branch, facing each other in a more “egalitarian” position. In aquatic animals such as Gray Whales, West Indian Manatees, Bottlenose Dolphins, and Botos, males rub their penises together or stimulate each other while rolling and clasping one another in constantly shifting, fluid body positions that defy any categorization as “mounter” or “mountee.” Reciprocal rump rubbing and genital stimulation—found in Chimpanzees and some Macaques—also renders meaningless a dominance-based view of homosexual interactions. When two males or two females back toward each other and rub their anal and genital regions together, sometimes also manually stimulating each other’s genitals—which one is “dominating” the other? Or when a male Vampire Bat grooms his partner, licking his genitals while simultaneously masturbating himself, which one is behaving “submissively”? By the same token, Crested Black Macaque females have a unique form of mutual masturbation in which they stand side by side facing in opposite directions and stimulate each other’s clitoris—again, because of the pure reciprocity, it makes little sense to interpret this behavior as expressing some sort of hierarchical relationship between the partners.

Genital rubbing, masturbation of one’s partner, oral sex, anal stimulation other than mounting, and sexual grooming occur among same-sexed individuals in more than 70 species—yet virtually all of these forms of sexual expression fall outside the realm of clear-cut dominance relationships. 89These more mutual, reciprocal, or dominance-ambiguous sexual activities are commonly found alongside homosexual mounting behavior in the same species—but the former are typically ignored when a dominance analysis is advocated. 90Ironically, another entire sphere of homosexual activity eludes a dominance interpretation—any same-sex interaction that is not overtly sexual. Courtship, affectionate, pair-bonding, and parenting behaviors that do not involve genital contact or direct sexual arousal—yet still occur between same-sex partners—are routinely omitted from any discussion of the relevance of dominance to the expression of homosexuality. 91The exclusion of nonsexual behaviors such as these from dominance considerations contrasts, paradoxically, with the way that mounting behavior itself is ultimately rendered nonsexual by its inclusion under the category of dominance.

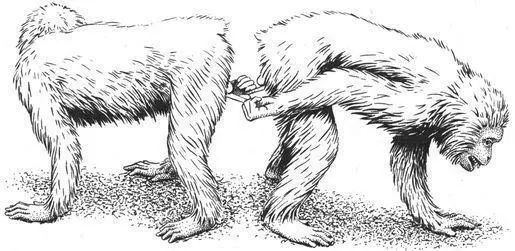

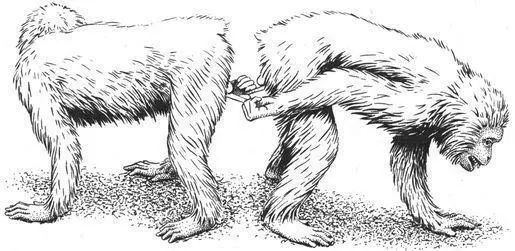

Male Stumptail Macaques manually stimulating each other’s genitals. Mutual or reciprocal sexual behaviors such as this are good examples of homosexual activity that is not “dominance” oriented.

A final indictment of a dominance analysis is that the purported ranking of individuals based on their mounting or other sexual behavior often fails to correspond with other measures of dominance in the species. Male Giraffes, for example, have a well-defined dominance hierarchy in which the rank of an individual is determined by his age, size, and ability to displace other males with specific postures and stares. Homosexual mounting and “necking” behavior is usually claimed to be associated with dominance, yet a detailed study of the relationship between these activities and an individual’s social standing according to other measures revealed no connection whatsoever. Mounting position also fails to reflect an individual’s rank as measured by aggressive encounters (e.g., threat and attack behavior) and other criteria in male Crested Black Macaques, male Stumptail Macaques, and female Pig-tailed Macaques. In only about half of all male homosexual mounts among Savanna (Olive) Baboons is there a correlation between dominance status, as determined in aggressive or playful interactions, and the role of an animal as mounter or mountee. In male Squirrel Monkeys, dominance status affects an individual’s access to food, heterosexual mating opportunities, and the nature of his interactions with other males, yet the rank of males as evidenced by their participation in homosexual genital displays does not correspond in any straightforward way to these other criteria. Among male Red Squirrels, there is no simple relationship between aggressiveness and same-sex mounting: the most aggressive individual in one study population indeed mounted other males the most frequently, yet he was also the recipient of mounts by other males the most often, while the least aggressive male was hardly ever mounted by any other males. This is also true for Spinifex Hopping Mice, in which males typically mount males who are more aggressive than themselves. Similarly, although male Bison fairly consistently express dominance through displays such as chin-raising and head-to-head pushing, these behaviors do not offer a reliable predictor of which will mount the other. Although some mounts between male Pukeko appear to be correlated with the dominance status of the participants (as determined by their feeding behavior, age, size, and other factors), there is no consistent relationship between these measures of dominance and another important indicator of rank—a male’s access to heterosexual copulations (or the number of offspring he fathers). Finally, dominance relations in Sociable Weavers are not always uniform across different measures either: one male, for example, was “dominant” to another according to their mounting behavior, yet “subordinate” to him according to their pecking and threat interactions. 92

Читать дальше