Description

Behavioral Expression: The majority of male Blackbucks have homosexual interactions: among all age groups, mounting of one male by another occurs in the position used for heterosexual intercourse. Usually mounting happens during play-fighting—friendly sparring matches with erotic overtones, sometimes involving three males at a time. In addition, adult males often perform courtship displays toward adolescent males (one-to-two-year-olds) prior to mounting them. These displays, which also occur in heterosexual interactions, begin with the older male DISPLAY WALKING: he stands some distance away from the object of his attentions, lowering his ears and curling his tail up to touch his back. He walks in this posture parallel to the younger male so that the younger one has to walk in a circle. This is followed by PRESENTING THE THROAT: the older male raises his nose high in the air so that his spiral horns touch the back of his neck. This exposes the striking black-and-white pattern of his neck. While doing this, he briskly kicks first one foreleg, then the other, in front of him several times in a row, sometimes reaching under the other male’s belly or between his thighs. Occasionally, the older male makes a distinctive barking sound as he does this. This is then followed by mounting of the younger male by the older. Occasionally, female Blackbucks mount other females.

A male Blackbuck mounting another male during a bout of play-fighting

In Thomson’s Gazelles, male homosexual mounting may occur in a variety of contexts, including during migration and in encounters between two nonterritorial males. Males also occasionally direct courtship displays toward one another, including the NECK-STRETCH, FORELEG KICK, and NOSE-UP POSTURE, as well as the PURSUIT MARCH (the latter similar to heterosexual courtships). Homosexual courtship displays are preceded by one or both males displaying their horns to the other (often interpreted as a threatening gesture). Homosexual mounting in Grant’s Gazelles typically occurs as part of a formalized display in which two males march toward one another, lifting their heads high and showing their white throat patches when they are next to each other. The mounted male, if an adult, often attacks the male trying to mount him (females also sometimes respond aggressively to a male’s advances, see below).

Frequency: Male homosexual activity is common among Blackbucks: at any given time, fully three-quarters of the male population lives in the bachelor herds, where most homosexual interactions take place. Among Thomson’s and Grant’s Gazelles, homosexual behavior is much less frequent: 12 percent of encounters between male Grant’s involve mounting, while 1–8 percent of encounters between male Thomson’s involve sexual behavior.

Orientation: All Blackbuck males over three years old leave the bachelor herd temporarily to attempt mating with females. However, this usually occurs only once or twice in each male’s lifetime; for the remainder of his life, he interacts homosexually. Technically, then, all male Blackbuck are bisexual, though in practice they are predominantly homosexual. In Thomson’s Gazelles, homosexual mounting typically occurs among males in bachelor or migratory groups, not territorial males (who are involved principally in heterosexual activities). Although these males occasionally court and attempt to mount females, the majority of their sexual interactions may be with other males. In Grant’s males, homosexual behavior does occur in some territorial males; since these males direct sexual behaviors toward both males and females, they are functionally bisexual (although males generally do not consent to being mounted by other males).

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Because of the organization of Blackbuck society into sex-segregated herds and the small number of active breeding males, only a fraction of the male population is ever involved in heterosexual activity. Furthermore, although all males attempt to leave the bachelor herds and mate with females, most are unable to do so because of the males already defending the breeding territories; consequently life in the bachelor herd is preferable for many males. Among Grant’s and Thomson’s Gazelles, there are similar patterns of sex segregation and nonparticipation in heterosexuality—in fact, more than 90 percent of the male Grant’s population may be composed of nonbreeders at any given time. In addition, female Grant’s Gazelles often behave aggressively toward males during heterosexual courtship, performing threat displays and sometimes even fighting bucks to fend off unwanted advances. Female Blackbucks sometimes engage in nonreproductive mounts of fawns or young animals.

Sources

*asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender

*Dubost, G., and F. Feer (1981) “The Behavior of the Male Antilope cervicapra L., Its Development According to Age and Social Rank.” Behavior 76:62–127.

*Schaller, G. B. (1967) The Deer and the Tiger. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Walther, F. R. (1995) In the Country of Gazelles. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

*———(1978a) “Quantitative and Functional Variations of Certain Behavior Patterns in Male Thomson’s Gazelle of Different Social Status.” Behavior 65:212–40.

*———(1978b) “Forms of Aggression in Thomson’s Gazelle; Their Situational Motivation and Their Relative Frequency in Different Sex, Age, and Social Classes.” Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 47:113–72.

*———(1974) “Some Reflections on Expressive Behavior in Combats and Courtship of Certain Horned Ungulates.” In V. Geist and F. Walther, eds., Behavior in Ungulates and Its Relation to Management, vol. 1, pp. 56–106. IUCN Publication no. 24. Morges, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

———(1972) “Social Grouping in Grant’s Gazelle ( Gazella granti Brooke, 1827[sic])” in the Serengeti National Park.” Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 31:348–403.

*———(1965) “Verhaltensstudien an der Grantgazelle (Gazella granti Brooke, 1872) im Ngorogoro-Krater [Behavioral Studies on Grant’s Gazelle in the Ngorogoro Crater].” Zeitshcrift für Tierpsychologie 22:167-208.

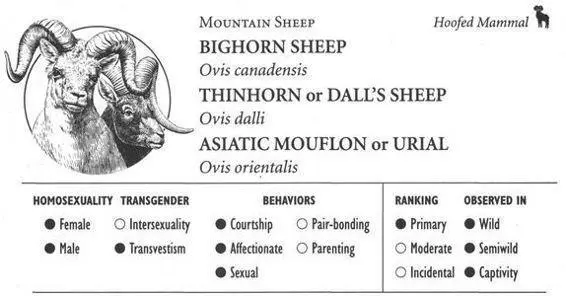

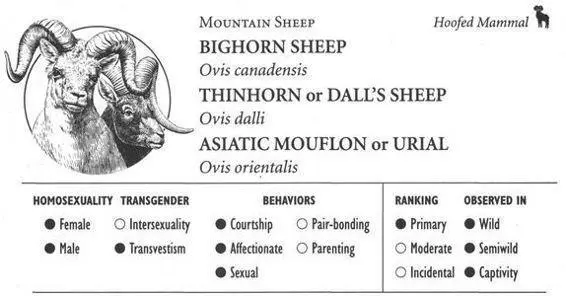

WILD SHEEP, GOATS, AND BUFFALO

BIGHORN SHEEP

IDENTIFICATION: A large wild sheep (weighing up to 300 pounds) with massive spiral horns in males; coat is brown with a white muzzle, underparts, and rump patch. DISTRIBUTION: Southwestern Canada, Rocky Mountains to northern Mexico. HABITAT: Mountain and desert rocky terrain. STUDY AREAS: Banff National Park, Alberta; Kootenay National Park and the Chilcotin-Cariboo Region, British Columbia, Canada; National Bison Range, Montana; subspecies O.c. canadensis, the Rocky Mountain Bighorn, and O.c. californiana, the California Bighorn Sheep.

THINHORN SHEEP

IDENTIFICATION: Similar to Bighorn, except smaller and with thinner horns; coat is all white or brownish black to gray, DISTRIBUTION: Alaska, northwestern Canada. HABITAT: Rocky alpine and arctic terrain. STUDY AREAS: Kluane Lake, the Yukon; Cassiar Mountains, British Columbia, Canada; subspecies O.d. dalli, Dall’s Sheep, and O.d. stonei, Stone’s Sheep.

Читать дальше