*Salter, R. E. (1979) “Observations on Social Behavior of Atlantic Walruses (Odobenus rosmarus [L.]) During Terrestrial Haul-Out.” Canadian Journal of Zoology 58:461-63.

Schevill, W. E., W. A. Watkins, and C. Ray (1966) “Analysis of Underwater Odobenus Calls with Remarks on the Development and Function of the Pharyngeal Pouches.” Zoologica 51:103-6.

*Sjare, B., and I. Stirling (1996) “The Breeding Behavior of Atlantic Walruses, Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus, in the Canadian High Arctic.” Canadian Journal of Zoology 74:897-911.

Stirling, I., W. Calvert, and C. Spencer (1987) “Evidence of Stereotyped Underwater Vocalizations of Male Atlantic Walruses ( Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus ).” Canadian Journal of Zoology 65:2311-21.

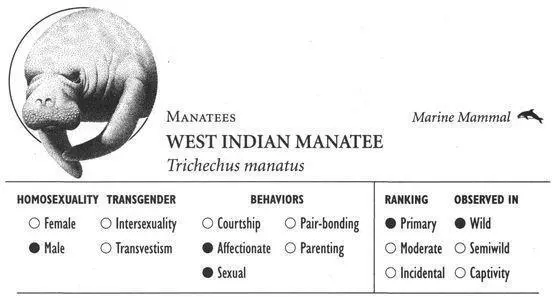

IDENTIFICATION: A large (8-14 foot), streamlined, seal-like animal with a rounded tail, foreflippers but no hind legs, and a thick, hairless skin. DISTRIBUTION: Coastal waters and rivers of southeastern United States, the Caribbean, and northeastern Brazil; vulnerable. HABITAT: Shallow tropical and subtropical waters with abundant aquatic plants. STUDY AREAS: Crystal and Homosassa Rivers, Florida; subspecies T.m. latirostris, the Florida Manatee.

Social Organization

West Indian Manatees are generally solitary and only moderately social; however, they may congregate in loose herds of two to six animals. Some herds are cosexual, while others are “bachelor” groups of younger males.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Male West Indian Manatees of all ages regularly engage in intense homosexual activities. In a typical encounter, two males embrace, rub their genital openings against each other, and then unsheathe or erect their penises and rub them together, often to ejaculation. During a homosexual mating, the two males often tumble to the bottom, thrusting against each other and wallowing in the mud as they clasp each other tightly. A wide variety of positions are used, including embracing in head-to-tail and sideways positions, often with interlocking penises or flipper-penis contact. All of these are distinct from the position used for heterosexual copulation, in which the male typically swims underneath the female on his back and mates with her upside down. Lasting for up to two minutes, homosexual copulations are generally four to eight times longer than heterosexual ones. Before they engage in sexual activity, males often “kiss” each other by touching their muzzles at the surface of the water. In addition, several other types of affectionate and tactile activities are a part of homosexual interactions, including mouthing and caressing of each other’s body, nibbling or nuzzling of the genital region, and riding by one male on the back of the other (a behavior also seen in heterosexual interactions). Sometimes a male emits vocalizations indicating his pleasure during homosexual activity, variously described as high-pitched squeaks, chirp-squeaks, or snort-chirps. If, however, he is not interested in participating, he may emit a squealing sound, slapping his tail as he flees from the other male (just the way females do when trying to escape from unwanted advances of males).

Often several males participate at the same time in homosexual interactions: groups of up to four animals have been seen kissing, embracing each other in an interlocked “hug,” thrusting, and rubbing their penises against one another. These homosexual “orgies” can last for hours as new males arrive to join the group, subgroups form and re-form, and participants leave and return. Homosexual behavior is often part of a social activity known as CAVORTING, in which animals travel and splash about in groups, nuzzling, grabbing, chasing, rubbing, and rolling against one another. Cavorting groups can be mixed-sex or all-male.

Frequency: Homosexuality is common among West Indian Manatees. In addition, males spend on average about 11 percent of their time in cavorting groups.

Orientation: Most male Manatees are probably bisexual, since homosexual behavior is sometimes interspersed with, or develops out of, heterosexual interactions when more than one male is involved. However, much homosexual activity occurs independent of heterosexual activity, and some males may engage primarily in same-sex interactions.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Heterosexual interactions in West Indian Manatees often involve considerable harassment and coercion of females by males. Large, jostling herds containing as many as 17-22 males relentlessly pursue females in heat as well as nonfertilizable females, attempting to copulate with them and often following them for weeks at a time. In her attempts to escape from the males, the female may violently slap her tail, twisting and turning as she dives away, or else tear through the underwater vegetation, even plunging into the mud or stranding herself onshore. Calves whose mothers are being pursued sometimes get lost or are fatally fatigued or injured. Female Manatees generally reproduce only once every three years, and at any given time, only about 30-40 percent of all females are reproducing. Most male Manatees have a distinct seasonal sexual cycle as well, with their testes generally dormant and not producing sperm during the winter months. Females raise their young on their own with no help from the males. However, a mother will occasionally allow another female to nurse her calf or may leave her calf in the company of other mothers and/or their calves while she goes off to feed on her own.

Other Species

Homosexual activity has also been observed in Dugongs (Dugong dugon), a species of Manatee that inhabits Australasian waters. A pair of captive males, for example, engaged in courtship and sexual behaviors with each other, including rolling, nudging, gentle biting, and splashing, often with erect penises. Although same-sex activity has yet to be documented in wild Dugongs, most observations of mating activity for this species in the wild involve individuals whose sex has not been unequivocally determined.

Sources

*asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender

*Anderson, P. K. (1997) “Shark Bay Dugongs in Summer. I: Lek Mating.” Behavior 134:433–62.

*Bengtson, J. L. (1981) “Ecology of Manatees (Trichechus manatus) in the St. Johns River, Florida.” Ph.D. thesis, University of Minnesota.

*Hartman, D. S. (1979) Ecology and Behavior of the Manatee (Trichechus manatus) in Florida. American Society of Mammalogists Special Publication no. 5. Pittsburgh: American Society of Mammalogists.

*———(1971) “Behavior and Ecology of the Florida Manatee, Trichechus manatus latirostris (Harlan), at Crystal River, Citrus County.” Ph.D. thesis, Cornell University.

Hernandez, P., J. E. Reynolds, III, H. Marsh, and M. Marmontel (1995) “Age and Seasonality in Spermatogenesis of Florida Manatees.” In T. J. O’Shea, B. B. Ackerman, and H. F. Percival, eds., Population Biology of the Florida Manatee, pp. 84–97. Information and Technology Report 1. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior.

Husar, S. L. (1978) “Trichechus manatus.” Mammalian Species 93:1–5.

*Jones, S. (1967) “The Dugong Dugong dugon (Müller): Its Present Status in the Seas Round India with Observations on Its Behavior in Captivity.” International Zoo Yearbook 7:215–20.

Читать дальше