*Brown, D. H., and K. S. Norris (1956) “Observations of Captive and Wild Cetaceans.” Journal of Mammalogy 37:311–26.

*Caldwell, M. C., and D. K. Caldwell (1977) “Cetaceans.” In T.A. Sebeok, ed., How Animals Communicate, pp. 794–808. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

*———(1972) “Behavior of Marine Mammals.” In S. H. Ridgway, ed., Mammals of the Sea: Biology and Medicine , pp. 419-65. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas.

*———(1967) “Dolphin Community Life.” Quarterly of the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History 5(4):12–15.

*Connor, R. C., and R. A. Smolker (1995) “Seasonal Changes in the Stability of Male-Male Bonds in Indian Ocean Bottlenose Dolphins ( Tursiops sp.).” Aquatic Mammals 21:213–16.

*Connor, R. C., R. A. Smolker, and A. F. Richards (1992) “Dolphin Alliances and Coalitions.” In A. H. Harcourt and F. B. M. de Waal, eds., Coalitions and Alliances in Humans and Other Animals , pp. 415–43. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

*Dudok van Heel, W. H., and M. Mettivier (1974) “Birth in Dolphins ( Tursiops truncatus ) in the Dolfinar-ium, Harderwijk, Netherlands.” Aquatic Mammals 2:11–22.

*Félix, F. (1997) “Organization and Social Structure of the Coastal Bottlenose Dolphin Tursiops truncatus in the Gulf of Guayaquil, Ecuador.” Aquatic Mammals 23:1-16.

*Herzing, D. L. (1996) “Vocalizations and Associated Underwater Behavior of Free-ranging Atlantic Spotted Dolphins, Stenella frontalis and Bottlenose Dolphins, Tursiops truncatus .” Aquatic Mammals 22:61–79.

*Herzing, D. L., and C. M. Johnson (1997) “Interspecific Interactions Between Atlantic Spotted Dolphins ( Stenella frontalis ) and Bottlenose Dolphins ( Tursiops truncatus ) in the Bahamas, 1985–1995.” Aquatic Mammals 23:85–99.

*Irvine, A. B., M. D. Scott, R. S. Wells, and J. H. Kaufmann (1981) “Movements and Activities of the Atlantic Bottlenose Dolphin, Tursiops truncatus , Near Sarasota, Florida.” Fishery Bulletin , U.S. 79:671–88.

*McBride, A. F., and D. O. Hebb (1948) “Behavior of the Captive Bottle-Nose Dolphin, Tursiops truncatus .” Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology 41:111–23.

*Nakahara, F., and A. Takemura (1997) “A Survey on the Behavior of Captive Odontocetes in Japan.” Aquatic Mammals 23:135–43.

*Nishiwaki, M. (1953) “Hermaphroditism in a Dolphin ( Prodelphinus caeruleo-albus ).” Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute 8:215–18.

*Norris, K. S., and T. P. Dohl (1980a) “Behavior of the Hawaiian Spinner Dolphin, Stenella longirostris .” Fishery Bulletin , U.S . 77:821-49.

*———(1980b) “The Structure and Functions of Cetacean Schools.” In L. M. Herman, ed., Cetacean Behavior: Mechanisms and Functions , pp. 211–61. New York: Wiley-InterScience.

*Norris, K. S., B. Würsig, R. S. Wells, and M. Würsig (1994) The Hawaiian Spinner Dolphin . Berkeley: University of California Press.

*Östman, J. (1991) “Changes in Aggressive and Sexual Behavior Between Two Male Bottlenose Dolphins ( Tursiops truncatus ) in a Captive Colony.” In K. Pryor and K. S. Norris, eds., Dolphin Societies: Discoveries and Puzzles , pp. 304-17. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Patterson, I. A. P., R. J. Reid, B. Wilson, K. Grellier, H. M. Ross, and P. M. Thompson (1998) “Evidence for Infanticide in Bottlenose Dolphins: an Explanation for Violent Interactions with Harbor Porpoises?” Proceedings of the Royal Society of London , Series B 265:1167–70.

*Saayman, G. S., and C. K. Tayler (1973) “Some Behavior Patterns of the Southern Right Whale, Eubalaena australis.” Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde 38:172–83.

Samuels, A., and T. Gifford (1997) “A Quantitative Assessment of Dominance Among Bottlenose Dolphins.” Marine Mammal Science 13:70–99.

Shane, S. H. (1990) “Behavior and Ecology of the Bottlenose Dolphin at Sanibel Island, Florida.” In S. Leatherwood and R. R. Reeves, eds., The Bottlenose Dolphin , pp. 245-65. San Diego: Academic Press.

Shane, S. H., R. S. Wells, and B. Würsig (1986) “Ecology, Behavior, and Social Organization of the Bottlenose Dolphin: A Review.” Marine Mammal Science 2:34–63.

*Tavolga, M. C. (1966) “Behavior of the Bottlenose Dolphin ( Tursiops truncatus ): Social Interactions in a Captive Colony.” In K. S. Norris, ed., Whales, Dolphins, and Porpoises , pp. 718-30. Berkeley: University of California Press.

*Tayler, C. K., and G. S. Saayman (1973) “Imitative Behavior by Indian Ocean Bottlenose Dolphins ( Tursiops aduncus ) in Captivity.” Behavior 44:286-98.

*Wells, R. S. (1995) “Community Structure of Bottlenose Dolphins Near Sarasota, Florida.” Paper presented at the 24 thInternational Ethological Conference, Honolulu, Hawaii.

*———(1991) “The Role of Long-Term Study in Understanding the Social Structure of a Bottlenose Dolphin Community.” In K. Pryor and K. S. Norris, eds., Dolphin Societies: Discoveries and Puzzles , pp. 199–225. Berkeley: University of California Press.

*———(1984) “Reproductive Behavior and Hormonal Correlates in Hawaiian Spinner Dolphins, Stenella longirostris .” In W. E Perrin, R. L. Brownell, Jr., and D. P. DeMaster, eds., Reproduction in Whales , Dolphins, and Porpoises , pp. 465–72. Report of the International Whaling Commission, Special Issue 6. Cambridge, UK: International Whaling Commission.

*Wells, R. S., K. Bassos-Hull, and K. S. Norris (1998) “Experimental Return to the Wild of Two Bottlenose Dolphins.” Marine Mammal Science 14:51–71.

*Wells, R. S., M. D. Scott, and A. B. Irvine (1987) “The Social Structure of Free-ranging Bottlenose Dolphins.” In H. Genoways, ed., Current Mammalogy , vol. 1, pp. 247–305. New York: Plenum Press.

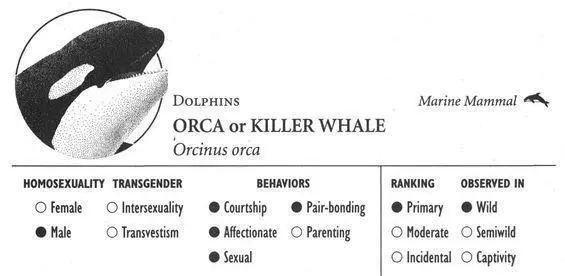

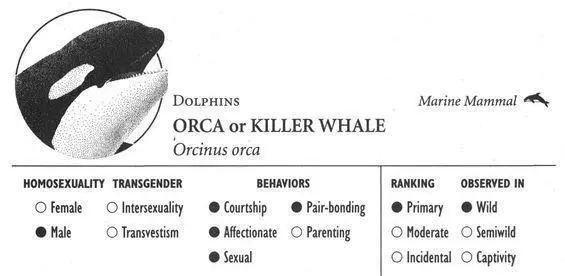

IDENTIFICATION: The largest member of the dolphin family (16–26 feet in length); a tall dorsal fin and distinctive black-and-white markings. DISTRIBUTION: Seas and oceans worldwide. HABITAT: Often found in coastal waters. STUDY AREAS: Johnstone Strait, Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada; Puget Sound, Washington.

Social Organization

Killer Whales live in a complex society based on a female-centered social unit called the MATRILINEAL GROUP. This is made up of an adult female, the matriarch—usually reproductively active, but sometimes older and postreproductive—her young, and any adult sons of hers. Sometimes her mother or grandmother is also present, and possibly her brothers or uncles. Matrilineal groups usually contain three or four Orcas (although some have up to nine); these groups are organized into larger social units known as PODS, which tend to socialize together and share a common dialect in their vocalizations. Some populations of Killer Whales are TRANSIENTS, who travel widely in smaller groups (occasionally singly) and are less vocal. Unlike nontransient or RESIDENT Orcas, they feed primarily on marine mammals rather than fish.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Homosexual interactions are an integral and important part of male Orca social life. During the summer and fall—when resident pods join together to feast on the salmon runs—males of all ages often spend the afternoons in sessions of courtship, affectionate, and sexual behaviors with each other. A typical homosexual interaction begins when a male Killer Whale leaves his matrilineal group to join a temporary male-only group; a session can last anywhere from a few minutes to more than two hours, with the average length being just over an hour. Usually only two Orcas participate at a time, although groups of three or four males are not uncommon, and even five participants at one time have been observed. The males roll around with each other at the surface, splashing and making frequent body contact as they rub, chase, and gently nudge one another. This is usually accompanied by acrobatic displays such as vigorous slapping of the water with the tail or flippers, lifting the head out of the water (SPYHOPPING), arching the body while floating at the surface or just before a dive, and vocalizing in the air. Particular attention is paid by the males to each other’s belly and genital region, and often they initiate a behavior known as BEAK-GENITAL ORIENTATION, which is also seen in heterosexual courtship and mating sequences. Just below the surface of the water, one male swims underneath the other in an upside-down position, touching and nuzzling the other’s genital area with his snout or “beak.” The two males swim together in this position, maintaining beak-genital contact as the upper one surfaces to breathe; then they dive together, spiraling down into the depths in an elegant double-helix formation. As a variation on this sequence, sometimes one male will arch his tail flukes out of the water just before a dive, allowing the other male to rub his beak against his belly and genital area. When the pair resurfaces after three to five minutes, they repeat the sequence, but with the positions of the two males reversed. In fact, almost 90 percent of all homosexual behaviors are reciprocal, in that the males take turns touching or interacting with one another. During all of these interactions, the Orcas frequently display their erect penises, rolling at the surface or underwater to reveal the distinctive yard-long, pink organs. One male may even attempt to insert his penis—which has a prehensile tip that can be independently moved—into the genital slit of another male (although this has yet to be fully verified).

Читать дальше