*Kano, T. (1992) The Last Ape: Pygmy Chimpanzee Behavior and Ecology. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Translated from the Japanese by Evelyn Ono Vineberg.

*———(1990) “The Bonobos’ Peaceable Kingdom.” Natural History 99(11):62–71.

*———(1989) “The Sexual Behavior of Pygmy Chimpanzees.” In P. G. Heltne and L. A. Marquardt, eds., Understanding Chimpanzees, pp.176–83. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

*———(1980) “Social Behavior of Wild Pygmy Chimpanzees (Pan paniscus) of Wamba: A Preliminary Report.” Journal of Human Evolution 9:243–60.

*Kitamura, K. (1989) “Genito-Genital Contacts in the Pygmy Chimpanzee (Pan paniscus).” African Study Monographs 10:49–67.

*Kuroda, S. (1984) “Interactions Over Food Among Pygmy Chimpanzees.” In R. L. Susman, ed., The Pygmy Chimpanzee: Evolutionary Biology and Behavior, pp. 301–24. New York: Plenum Press.

*———(1980) “Social Behavior of Pygmy Chimpanzees.” Primates 21:181–97.

*Parish, A. R. (1996) “Female Relationships in Bonobos (Pan paniscus): Evidence for Bonding, Cooperation, and Female Dominance in a Male-Philopatric Species.” Human Nature 7:61–96.

*———(1994) “Sex and Food Control in the ‘Uncommon Chimpanzee’: How Bonobo Females Overcome a Phylogenetic Legacy of Male Dominance.” Ethology and Sociobiology 15:157–79.

*Roth, R. R. (1995) “A Study of Gestural Communication During Sexual Behavior in Bonobos (Pan paniscus Schwartz)”. Master’s thesis, University of Calgary.

Sabater Pi, J., M. Bermejo, G. Illera, and J. J. Vea (1993) “Behavior of Bonobos (Pan paniscus) Following Their Capture of Monkeys in Zaire.” International Journal of Primatology 14:797–804.

*Savage, S. and R. Bakeman (1978) “Sexual Morphology and Behavior in Pan paniscus.” In D. J. Chivers and J. Herbert, eds., Recent Advances in Primatology, vol. 1 , pp. 613–16. New York: Academic Press.

*Savage-Rumbaugh, E. S., and R. Lewin (1994) Kanzi: The Ape at the Brink of the Human Mind. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

*Savage-Rumbaugh, E. S., and B. J. Wilkerson (1978) “Socio-sexual Behavior in Pan paniscus and Pan troglodytes. A Comparative Study.” Journal of Human Evolution 7:327—44.

*Savage-Rumbaugh, E. S., B. J. Wilkerson and R. Bakeman (1977) “Spontaneous Gestural Communication among Conspecifics in the Pygmy Chimpanzee (Pan paniscus).” In G. Bourne, ed., Progress in Ape Research, pp. 97–116. New York: Academic Press.

*Takahata, Y, H. Ihobe, and G. Idani (1996) “Comparing Copulations of Chimpanzees and Bonobos: Do Females Exhibit Proceptivity or Receptivity?.” In W. C. McGrew, L. F. Marchant, and T. Nishida, eds., Great Ape Societies, pp. 146–55. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Takeshita, H., and V. Walraven (1996) “A Comparative Study of the Variety and Complexity of Object Manipulation in Captive Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and Bonobos (Pan paniscus).” Primates 37: 423-41.

*Thompson-Handler, N., R. K. Malenky, and N. Badrian (1984) “Sexual Behavior of Pan paniscus Under Natural Conditions in the Lomako Forest, Equateur, Zaire.” In R.L. Susman, ed., The Pygmy Chimpanzee: Evolutionary Biology and Behavior, pp. 347–68. New York: Plenum Press.

*de Waal, F. B. M. (1997) Bonobo: The Forgotten Ape. Berkeley: University of California Press.

*———(1995) “Sex as an Alternative to Aggression in the Bonobo.” In P. A. Abramson and S. D. Pinkerton, eds., Sexual Nature, Sexual Culture, pp. 37–56. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

*———(1989a) Peacemaking Among Primates. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

*———(1989b) “Behavioral Contrasts Between Bonobo and Chimpanzee.” In P. G. Heltne and L. A. Marquardt, eds., Understanding Chimpanzees, pp. 154-73. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

*———(1988) “The Communicative Repertoire of Captive Bonobos (Pan paniscus), Compared to That of Chimpanzees.” Behavior 106:184–251.

*———(1987) “Tension Regulation and Nonreproductive Functions of Sex in Captive Bonobos (Pan paniscus).” National Geographic Research 3:318–35.

Walraven , V., L. Van Elsacker, and R. F. Verheyen (1993) “Spontaneous Object Manipulation in Captive Bonobos.” In L. Van Elsacker, ed., Bonobo Tidings: Jubilee Volume on the Occasion of the 150th Anniversary of the Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp, pp. 25–34. Leuven: Ceuterick Leuven.

*White, F., and N. Thompson-Handler (1989) “Social and Ecological Correlates of Homosexual Behavior in Wild Pygmy Chimpanzees, Pan paniscus.” American Journal of Primatology 18:170.

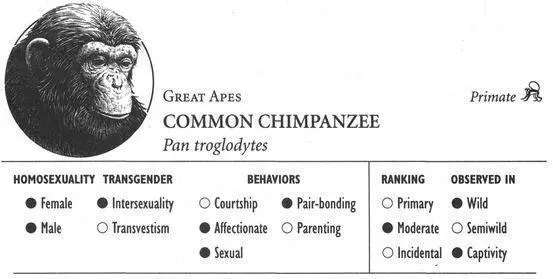

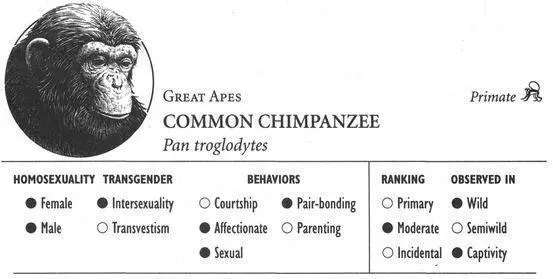

IDENTIFICATION: The familiar small ape, with black, gray, or brownish fur, prominent ears, and variable facial coloring, from black to brown and pink (especially in younger animals). DISTRIBUTION: Western and central Africa, from southeastern Senegal to western Tanzania; endangered. HABITAT: Woodland savanna, grassland, tropical rain forest. STUDY AREAS: Mahale Mountains National Park and the Gombe Stream National Park, Tanzania; Budongo Forest, Uganda; eastern Congo (Zaire); Arnhem Zoo, the Netherlands; Anthropoid Station, Tenerife; Yale University Primate Laboratory and chimpanzee colony (New Haven, Conn., Franklin, N.H., and Orange Park, Fla.); ARL Chimpanzee Colony, N.Mex.; Delta Regional Primate Research Center, La.; subspecies P.t. schweinfurthii.

Social Organization

Common Chimpanzees live in groups or communities of 40–60 individuals, usually with twice as many adult females as males. Within each group, smaller subgroups often form, and some individuals form longer-lasting bonds with each other as part of a complex network of social and communicative interactions. The mating system is promiscuous or polygamous: males and females each mate with multiple partners, and males do not generally participate in raising their own offspring.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Female Common Chimpanzees participate in a variety of same-sex activities. One form of mutual genital stimulation is sometimes known as BUMPRUMP: two females, standing on all fours and facing in opposite directions, rub their rumps together (usually in an up-and-down motion), stimulating their genital and anal regions. Sometimes one female lies on top of the other in a face-to-face position—or the two sit facing one another—rubbing their genitals together. Mounting also occurs in the front-to-back position typical of heterosexual mating. Unlike male-female mountings, though, the angle and position of the mounting female’s body and arms may be slightly different from that of a male, her pelvic thrusts may be slower or more perfunctory, and she may rub against the other female’s genitals with her belly rather than her own genital region. Occasionally female Chimps also engage in cunnilingus: one individual presents her buttocks by crouching in front of the other, who stimulates her external genitalia with her lips and tongue.

Among males, several different kinds of same-sex interactions occur. Manual contact or stimulation of a partner’s genitals, for example, can involve fondling, rubbing, or gripping of the penis and/or touching of the scrotum, sometimes while the partner makes pelvic thrusts that “bounce” his genitals on his partner’s hand. Chimps occasionally also engage in fellatio, mutual penis-rubbing while sitting face-to-face, mounting in a front-to-back position (sometimes with pelvic thrusts or body shaking), and even insertion of a finger into the partner’s anus and oralanal “grooming” in a 69 position. A number of these activities—notably genital touching, mounting, and anal contact—occur as ritualized sexual gestures in the context of greeting, enlisting of support, reconciliation, and/or reassurance. They are often combined with affectionate gestures between males such as embracing, kissing (including openmouthed contact), grooming, and genital kissing or nuzzling. Males who participate in such activities may be bonded together in a mutually supportive “friendship” or COALITION. Occasionally male Chimpanzees also interact sexually with male Savanna Baboons in the wild. One adolescent Chimp, for example, was observed holding and fondling the penis of an adult male Baboon.

Читать дальше