Whether we’re talking about ganders and geese or Ruffs and Reeves, whether it’s Botos and Bonobos or Pukus and Pukeko, male and female homosexuality can be either surprisingly similar to each other or decidedly distinctive from one another. In any case, a complex intersection of factors is involved in the expression of homosexuality in each gender. As with other aspects of animal homosexuality, preconceived ideas about how males and females act must be reassessed and refined when considering the full range of animal behaviors. In some species such as Silver Gulls, male and female homosexualities conform to stereotypes commonly held about similar human behaviors: females form stable, long-lasting lesbian pair-bonds and raise families while males participate in promiscuous homosexual activity. In other species these gender stereotypes are turned completely on their heads, as in Black Swans, where only males form long-term same-sex couples and raise offspring, and Sage Grouse, where only females engage in group “orgies” of homosexual activity. 26And in the majority of cases, male and female homosexualities present their own unique blends of behaviors and characteristics that defy any simplistic categorization—such as Bonobos, where sexual penetration occurs in female rather than male same-sex activity, where sexual interactions between adults and adolescents are a prominent feature of female interactions, and where males do not form strongly bonded relationships with each other the way females do, but engage in less homosexual activity overall and more affectionate activity such as openmouthed kissing. Once again, the diversity of animal homosexuality reveals itself down to the very last detail of expression.

A Hundred and One Lesbian Acts: Calculating the Frequency of Homosexual Behavior

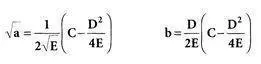

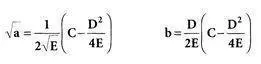

where a, b, C, D, and E represent the number of nests with 2-6 eggs respectively

—formulas used in estimating the number of female homosexual pairs in Gull populations 27

While studying Kob antelopes in Uganda, scientists recorded exactly 101 homosexual mounts between females. In Costa Rica, 2 copulations between males were observed during a study of Long-tailed Hermit Hummingbirds. In which species is homosexuality more frequent? The answer would appear to be obvious: Kob. However, simply knowing the total number of homosexual acts observed in each species is not sufficient to evaluate the prevalence of homosexuality. For example, it could be that the Kob were observed for a much longer period of time than the Hummingbirds, in which case the greater number of same-sex mounts would not necessarily reflect any actual difference between the two species. What we really need is a measure of the rate of homosexual activity—that is, the number of homosexual “acts” performed during a given period of time. To determine this, we have to know the duration of the study period for each species and how many animals were being observed. In this case, 8 female Kob antelopes were studied for a total of 67 hours, whereas 36 male Long-tailed Hermit Hummingbirds were observed over several hundred hours—so indeed the Kob have a much higher rate of same-sex activity (both in general and per individual), on the order of many hundreds of times higher than the Hummingbirds.

Rate of occurrence is only one measure of frequency, however. It could be that sexual activity in general is much rarer in Hummingbirds than in Kobs, in which case comparing absolute numbers or rates gives a distorted or incomplete picture. A more meaningful comparison would be to look at how many heterosexual acts are performed during the same time period and express the frequency of homosexual activity as a proportion of all sexual activity. In fact, sexual activity is incredibly common among Kob and much rarer in Long-tailed Hermits: during the same study period, 1,032 heterosexual mounts among Kob were tabulated while only 6 heterosexual matings in Hummingbirds were observed. Thus, homosexual mounts constitute only 9 percent of all sexual activity among the Kob, whereas one-fourth of all copulations in Long-tailed Hermits are between males. This is diametrically opposed to the frequency rate or absolute count of homosexual activity in the same species. 28

These two cases offer a good example of the many complications that arise when attempting to answer the question “How common or frequent is homosexuality in animals?” The most valid answer—clichés aside—is, “It depends.” It depends not only on the measure of frequency being used, but also on the species, the behaviors being tabulated, the observation techniques that are employed, and many other factors. In this section we’ll explore some of these factors and try to arrive at some meaningful generalizations about the prevalence of homosexuality in the animal kingdom.

One broad measure of frequency is the total number of species in which homosexuality occurs. Same-sex behavior (comprising courtship, sexual, pair-bonding, and parental activities) has been documented in over 450 species of animals worldwide. 29While this may seem like a lot of animals, it is in fact only a tiny fraction of the more than 1 million species that are known to exist. 30Even considering the two animal groups that are the focus of this book—mammals and birds—homosexual behavior is known to occur in roughly 300 out of a total of about 13,000 species, or just over 2 percent. However, comparing the number of species that exhibit homosexuality against all known species is probably an inaccurate measure, since only a fraction of existing species have been studied in any depth—and detailed study is usually required to uncover behaviors such as homosexuality. Scientists have estimated that at least a thousand hours of field observation are required before more unusual but important activities will become apparent in a species’ behavior, and relatively few animals have received this level of scrutiny. 31Unfortunately, it is not known exactly how many species have been studied to this depth, although it has been estimated that perhaps only 1,000–2,000 have begun to be adequately described. Using these figures, the proportion of animal species exhibiting homosexual behavior comes in at 15–30 percent—a significant chunk. 32

In fact, the percentage is probably even higher than this, when we consider how easy it is for common behaviors to be missed during even the most detailed of study. A caveat of any scientific endeavor, particularly biology, is that much remains to be learned and observed, and many secrets await discovery—and this is especially true where sexual behavior is concerned. Nocturnal or tree-dwelling habits, elusiveness, habitat inaccessibility, small size, and problems in identifying individual animals are just some of the factors that make field observations of sexuality in many species exceedingly difficult. 33Consider heterosexual mating, a behavior that is known to occur in all mammals and birds (and most other animals), usually with great regularity. 34Yet in many species this activity has never been seen: “Despite literally thousands of hours of observations made by biologists over many years in the West Indies, Hawaii, and elsewhere, actual copulation in humpback whales has yet to be observed.” 35Lucifer hummingbirds, northern rough-winged swallows, black-and-white warblers, red-tailed tropic birds, and several species of cranes (such as wattled and Siberian cranes) are just a handful of the birds in which heterosexual mating has never been recorded. In some cases, opposite-sex mating has been observed, but only a handful of times at most: in magnificent hummingbirds and black-headed grosbeaks, for example—the latter a common North American bird—copulation between males and females has only been seen once during the entire history of the scientific study of these species. Heterosexual copulation in Victoria’s Riflebirds was not documented until the mid-1990s (and then only several times), even though the species has been known to Western science for nearly a century and a half. During a ten-year study of Cheetahs, no opposite-sex matings were seen over the course of 5,000 hours of observation, and copulation has only been observed a total of five times in the wild during the entire scientific study of this animal. Similar patterns are characteristic of other species: in the akepa (a Hawaiian finch), only five copulations were witnessed during five years of study, only five heterosexual matings were seen in a four-year study of Spotted Hyenas, and only three matings in a three-year study of Agile Wallabies. Nests and eggs of many birds such as swallows and birds of paradise have yet to be discovered, while the first nest of the marbled murrelet was found in 1959, more than 170 years after discovery of the species by Western science.

Читать дальше