CHAPTER 19

The Sea Cradle

THE SHARKS HAVE never seen humans before. And few humans present have ever seen so many sharks.

Except for moonlight, the sharks have also never seen the equatorial night be anything other than dark and deep. Nor have the eel fish, which resemble 5-foot silver ribbons with fins and needle snouts as they skitter up to the research vessel White Holly ’s steel hull, entranced by shafts of color drilled into the night sea by spotlights from the captain’s deck. Too late, they notice that the waters here are boiling with dozens of white-tipped, black-tipped, and gray reef sharks racing in delirious circles that scream hunger.

A quick squall comes and goes, blowing a curtain of warm rain across the lagoon where the ship is anchored and drenching the remains of a deckside chicken dinner eaten over a plastic tarp stretched across the dive master’s table. Still, the scientists linger at the White Holly’s railing, fascinated by thousands of pounds of sharks—sharks proving that they rule the food pyramid here by snatching eel fish in mid-flight as they leap between swells. Twice a day for the past four days, these people have swum among such sleek predators, counting them and everything else alive in the water, from swirling rainbows of reef fish to iridescent coral forests; from giant clams lined with velvety, multihued algae down to microbes and viruses.

This is Kingman Reef, one of the hardest places to reach on Earth. To the naked eye, it barely exists: a change from cobalt blue to aquamarine is the main clue that a nine-mile-long coral boomerang lies submerged 15 meters below the surface of the Pacific, 1,000 miles southwest of Oahu. At low tide two islets rise barely a meter above the water, mere slivers consisting of giant clamshell rubble heaped by storms against the reef. During World War II, the U.S. Army designated Kingman a way-station anchorage between Hawaii and Samoa, but never used it.

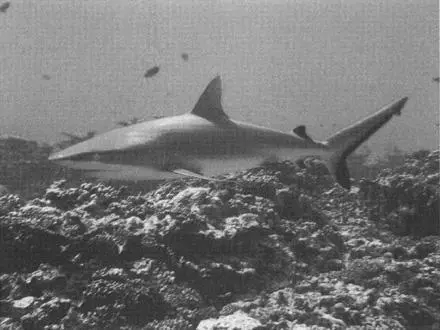

Gray reef shark. Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos . Kingman Reef.

J. E. MARAGOS, U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE.

Two dozen scientists aboard the White Holly and their sponsor, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, have come to this water-world-without-people to glimpse what a coral reef looked like before human beings appeared on Earth. Without such a baseline, there can be little agreement on what constitutes a healthy reef, let alone on how to help nurse these aquatic equivalents of rain forest diversity back to whatever that might be. Although months of sifting data lie ahead, already these researchers have found evidence that contradicts convention, and seems counterintuitive even to themselves. But there it is, thrashing just off starboard.

Between these sharks and an omnipresent species of 25-pound red snappers equipped with noticeable fangs—one of which sampled a photographer’s ear—it appears that big carnivores account for more total biomass than anything else here. If so, that would mean that at Kingman Reef, the conventional notion of a food pyramid is standing on its pointy head.

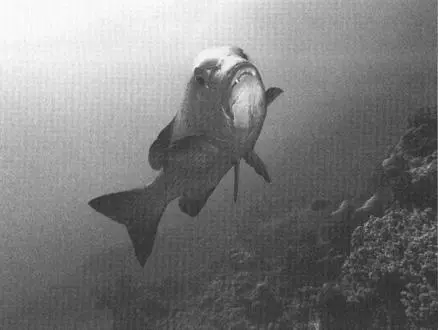

Two-spot red snapper. Lutjanus bohar , Palmyra Atoll.

J. E. MARAGOS, U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE.

As ecologist Paul Colinvaux described in a seminal 1978 book, Why Big Fierce Animals Are Rare , most animals feed on creatures smaller and many times more numerous than themselves. Because roughly only 10 percent of the energy they consume converts to body mass, millions of little insects must feast on 10 times their total weight in tiny mites. The bugs themselves are gobbled by a correspondingly smaller number of small birds, which in turn are hunted by far fewer foxes, wildcats, and large raptors.

Even more than by head counts, Colinvaux wrote, the food pyramid’s shape is defined by mass: “All the insects in a woodlot weigh many times as much as all the birds; and all the songbirds, squirrels, and mice combined weigh vastly more than all the foxes, hawks, and owls combined.”

None of the scientists on this August, 2005 expedition, who hail from America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia, would dispute those conclusions—on land. Yet the sea may be special. Or perhaps it’s terra firma that is the exception. In a world with or without people, two-thirds of its surface is that mutable one on which the White Holly lightly bobs to pulsations that rock the planet. From the vantage of Kingman Reef, there are no easy contours to define our spaces, because the Pacific has no boundaries. It stretches until it blends into the Indian and the Antarctic, and squeezes through the Bering Strait into the Arctic, all of which in turn mix into the Atlantic. At one time, the Earth’s great sea was the origin of everything that breathes and reproduces. As it goes, so goes everything’s future.

“Slime.”

Jeremy Jackson has to duck to take shade under an awning on the White Holly ’s upper deck, where the stern of this former naval cargo hauler has been converted to an invertebrate laboratory. Jackson, a Scripps marine paleoecologist with limbs and ponytail so long he suggests a king crab that short-circuited evolution, springing straight from the sea into human form, had the original idea for this mission. Jackson has spent much of his career in the Caribbean, watching the pressures of fishing and planetary warming flatten the Gruyère-cheese architecture of living coral reefs to bleached marine slag. As corals die and collapse, they and the myriad life-forms that call their crevices home, and everything that eats them, get displaced by something slick and unpleasant. Jackson leans over trays of algae that seaweed expert Jennifer Smith collected in previous stops on the way to Kingman.

“That’s what we get on the slippery slope to slime,” he tells her again. “Plus jellyfish and bacteria—the marine equivalent of rats and roaches.”

Four years earlier, Jeremy Jackson had been invited to Palmyra Atoll, the northernmost of the Line Islands: a tiny Pacific archipelago divided by the equator and split between two nations, Kiribati and the United States. Palmyra had recently been purchased by The Nature Conservancy for coral reef research. During World War II, the U.S. Navy built an air station on Palmyra, opened channels into one lagoon, and dumped enough munitions and 55-gallon diesel drums in another that it was later dubbed Black Lagoon for its resident pool of dioxins. Except for a small U.S. Fish and Wildlife maintenance staff, Palmyra is uninhabited, its abandoned naval buildings half-dissolved into the surf. One semi-submerged boat hull is now a planter box stuffed with coconut palms. Coconut, introduced here, has all but vanquished native pisonia forests, and rats have replaced land crabs as the top predator.

Jackson’s impression radically changed, however, when he jumped into the water. “I could barely see 10 percent of the bottom,” he told his Scripps colleague Enric Sala when he returned. “My view was blocked by sharks and big fish. You have to go there.”

Sala, a young conservation marine biologist from Barcelona, had never known big sea species in his native Mediterranean. In a strictly policed reserve off Cuba, he had seen a remnant population of 300-pound groupers. Jeremy Jackson had traced Spanish maritime records back to Columbus to verify that 800-pound versions of these monsters once spawned in huge numbers around Caribbean reefs, in the company of 1,000-pound sea turtles. On Columbus’s second voyage to the New World, the seas off the Greater Antilles were so thick with green turtles that his galleons practically ran aground on them.

Читать дальше