In less time than that, Pan prior became us. Should some equally ingenious, confounding, lyrical, and conflicted species appear on Earth again in our aftermath, they may still find T.R.’s fierce, shrewd gaze fixed intently upon them.

CHAPTER 13

The World Without War

WAR CAN DAMN Earthly ecosystems to hell: witness Vietnam’s poisoned jungles. Yet without chemical additives, war curiously has often been nature’s salvation. During Nicaragua’s Contra War of the 1980s, with shellfish and timber exploitation paralyzed along the Miskito Coast, exhausted lobster beds and stands of Caribbean pine impressively rebounded.

That took less than a decade. And in just 50 years without humans….

THE HILLSIDE IS heavily booby-trapped, which is why Ma Yong-Un admires it. Or rather, he admires the mature stands of daimyo oak, Korean willow, and bird cherry growing wherever land mines have kept people out.

Ma Yong-Un, who coordinates international campaigns at the Korean Federation for Environmental Movement, is climbing through cottony November fog in a white propane-powered Kia van. His companions are conservation specialist Ahn Chang-Hee, wetlands ecologist Kim Kyung-Won, and wildlife photographers Park Jong-Hak and Jin Ik-Tae. They’ve just cleared a South Korean military checkpoint, slaloming through a maze of black and yellow concrete barriers as they entered this restricted area. The guards, in winter camouflage fatigues, set aside their M16s to greet the KFEM team—since the last time they were here, a year earlier, a sign was added stating that this post is also an environmental checkpoint for preservation of red-crowned cranes.

While waiting for their paperwork, Kim Kyung-Won had made note of several gray-headed woodpeckers, a pair of long-tailed tits, and the bell-like singing of a Chinese bulbul in the dense brush around the checkpoint. Now, as the van ascends, they flush a brace of ring-necked pheasants and several azure-winged magpies, beautiful birds no longer common elsewhere in Korea.

They have entered a strip of land five kilometers deep that lies just below South Korea’s northern limit, called the Civilian Control Zone. Nearly no one has lived in the CCZ for half a century, although farmers have been permitted to grow rice and ginseng here. Five more kilometers of dirt road, flanked by barbed wire filled with perching turtle doves and hung with red triangles warning of more minefields, and they reach a sign in Korean and English that says they are entering the Demilitarized Zone.

The DMZ, as it is called even in Korea, is 151 miles long and 2.5 miles wide, and has been a world essentially without people since September 6, 1953. A final exchange of prisoners had ended the Korean War—except, like the conflict that tore Cyprus in two, it never really ended. The division of the Korean Peninsula had begun when the Soviet Union declared war on Japan late in World War II, on the same day that the United States dropped a nuclear warhead on Hiroshima. Within a week, that war was over. An agreement by the Americans and the Soviets to split the administration of Korea, which Japan had occupied since 1910, became the hottest point of contact for what became known as the Cold War.

Abetted by its Chinese and Soviet communist mentors, North Korea invaded the South in 1950. Eventually, United Nations forces pushed them back. A 1953 truce ended what had become a stalemate along the original dividing line, the 38th parallel. A strip two kilometers on either side of it became the no-man’s-land known as the Demilitarized Zone.

Much of the DMZ runs through mountains. Where it follows the courses of rivers and streams, the actual demarcation line is in bottomland where, for 5,000 years before the hostilities began, people grew rice. Their abandoned paddies are now sown thickly with land mines. Since the armistice in 1953, other than brief military patrols or desperate, fleeing North Koreans, humans have barely set foot here.

In their absence, the netherworld between these enemy doppelgängers has filled with creatures that had practically nowhere else to go. One of the world’s most dangerous places became one of its most important—though inadvertent—refuges for wildlife that might otherwise have disappeared. Asiatic black bears, Eurasian lynx, musk deer, Chinese water deer, yellow-throated marten, an endangered mountain goat known as the goral, and the nearly vanished Amur leopard cling here to what may only be temporary life support—a slender fraction of the necessary range for a genetically healthy population of their kind. If everything north and south of Korea’s DMZ were suddenly to become a world without humans as well, they might have a chance to spread, multiply, reclaim their former realm, and flourish.

Ma Yong-Un and his conservation companions have no recollection of Korea without this geographic paradox binding its midriff. Now in their thirties, they were born in a nation that grew from poverty to prosperity while they themselves were growing. Immense economic success has made millions of South Koreans believe—like Americans, Western Europeans, and Japanese before them—that they can have everything. For these young men, that means having their country’s wildlife, too.

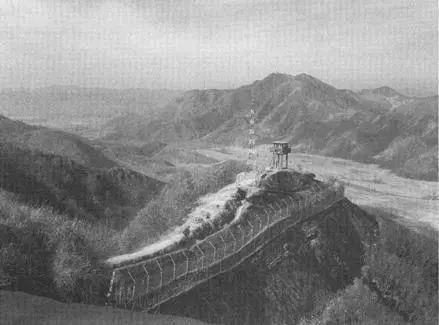

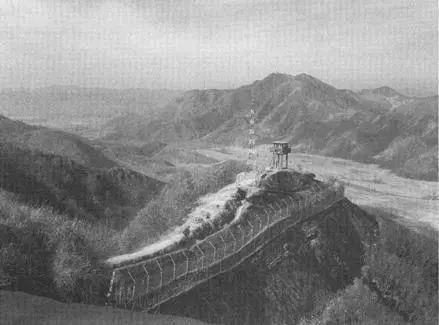

They arrive at a fortified observation bunker where South Korea has cheated. Here, the 151 miles of double fencing topped with coiled razor wire makes a sharp northward jog, following a promontory nearly one kilometer before looping back. That’s nearly half the distance that the truce obliges the two Koreas to maintain from the Demarcation Line, a faint string of posts down the DMZ’s middle that neither side is ever to approach.

“They do it, too,” Ma Yong-Un explains. Any place where a landform offers a view too irresistible to pass up, both sides seem to welcome opportunities to encroach and stare the other down. The camouflage paint on this artillery placement’s cinder blocks serves not to conceal but to display, like a belligerent cock bristling with threats and munitions in lieu of combs and feathers.

At the promontory’s northern edge, the DMZ opens into rugged fullness and vast emptiness for miles in either direction. Although each side has held fire since 1953, large loudspeakers atop South Korea’s positions have blasted regular insults, military anthems, and even strident themes like the William Tell Overture across the divide. The din has bounced off North Korean mountainsides that, over the decades, have been increasingly stripped bare for firewood. The inevitable tragic erosion has led to flooding, agricultural disasters, and famine. Should this entire peninsula one day be bereft of people, its ravaged northern half will take far longer to resuscitate biologically, while its southern half will leave far more infrastructure for nature to disassemble.

Korean DMZ.

PHOTO BY ALAN WEISMAN.

Below, in the buffer separating these vast extremes, are 5,000-year-old rice paddies that have reverted to wetlands during the last half-century. As the Korean naturalists watch, cameras and spotting scopes poised, over the bulrushes glides a dazzling white squadron, 11 fliers in perfect formation.

And in perfect silence. These are living Korean national icons: red-crowned cranes—the largest, and, next to whooping cranes, rarest on Earth. They’re accompanied by four smaller white-naped cranes, also endangered. Just in from China and Siberia, the DMZ is where most of them winter. If it didn’t exist, they probably wouldn’t either.

Читать дальше