Within 10 years, the downside to this wonder substance was apparent. Life Magazine coined the term “throwaway society,” though the idea of tossing trash was hardly new. Humans had done that from the beginning with leftover bones from their hunt and chaff from their harvest, whereupon other organisms took over. When manufactured goods entered the garbage stream, they were at first considered less offensive than smelly organic wastes. Broken bricks and pottery became the fill for the buildings of subsequent generations. Discarded clothing reappeared in secondary markets run by ragmen, or were recycled into new fabric. Defunct machines that accumulated in junkyards could be mined for parts or alchemized into new inventions. Hunks of metal could simply be melted down into something totally different. World War II—at least the Japanese naval and air portion—was literally constructed out of American scrap heaps.

Stanford archaeologist William Rathje, who has made a career of studying garbage in America, finds himself continually disabusing waste-management officials and the general public of what he deems a myth: that plastic is responsible for overflowing landfills across the country. Rathje’s decades-long Garbage Project, wherein students weighed and measured weeks’ worth of residential waste, reported during the 1980s that, contrary to popular belief, plastic accounts for less than 20 percent by volume of buried wastes, in part because it can be compressed more tightly than other refuse. Although increasingly higher percentages of plastic items have been produced since then, Rathje doesn’t expect the proportions to change, because improved manufacturing uses less plastic per soda bottle or disposable wrapper.

The bulk of what’s in landfills, he says, is construction debris and paper products. Newspapers, he claims, again belying a common assumption, don’t biodegrade when buried away from air and water. “That’s why we have 3,000-year-old papyrus scrolls from Egypt. We pull perfectly readable newspapers out of landfills from the 1930s. They’ll be down there for 10,000 years.”

He agrees, though, that plastic embodies our collective guilt over trashing the environment. Something about plastic feels uneasily permanent. The difference may have to do with what happens outside landfills, where a newspaper gets shredded by wind, cracks in sunlight, and dissolves in rain—if it doesn’t burn first.

What happens to plastic, however, is seen most vividly where trash is never collected. Humans have continuously inhabited the Hopi Indian Reservation in northern Arizona since AD 1000—longer than any other site in today’s United States. The principal Hopi villages sit atop three mesas with 360° views of the surrounding desert. For centuries, the Hopis simply threw their garbage, consisting of food scraps and broken ceramic, over the sides of the mesas. Coyotes and vultures took care of the food wastes, and the pottery sherds blended back into the ground they came from.

That worked fine until the mid-20th century. Then, the garbage tossed over the side stopped going away. The Hopis were visibly surrounded by a rising pile of a new, nature-proof kind of trash. The only way it disappeared was by being blown across the desert. But it was still there, stuck to sage and mesquite branches, impaled on cactus spines.

South of the Hopi Mesas rise the 12,500-foot San Francisco Peaks, home to Hopi and Navajo gods who dwell among aspens and Douglas firs: holy mountains cloaked in purifying white each winter—except in recent years, because snow now rarely falls. In this age of deepening drought and rising temperatures, ski lift operators who, the Indians claim, defile sacred ground with their clanking machines and lucre, are being sued anew. Their latest desecration is making artificial snow for their ski runs from wastewater, which the Indians liken to bathing the face of God in shit.

East of the San Francisco Peaks are the even taller Rockies; to their west are the Sierra Madres, whose volcanic summits are higher still. Impossible as it is for us to fathom, all these colossal mountains will one day erode to the sea—every boulder, outcrop, saddle, spire, and canyon wall. Every massive uplift will pulverize, their minerals dissolving to keep the oceans salted, the plume of nutrients in their soils nourishing a new marine biological age even as the previous one disappears beneath their sediments.

Long before that, however, these deposits will have been preceded by a substance far lighter and more easily carried seaward than rocks or even grains of silt.

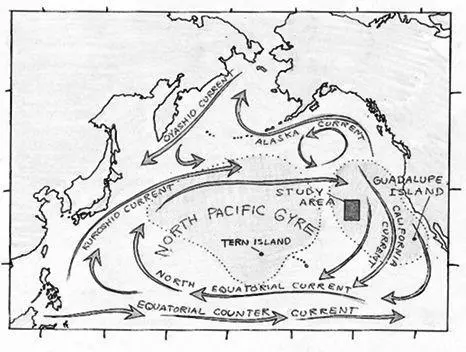

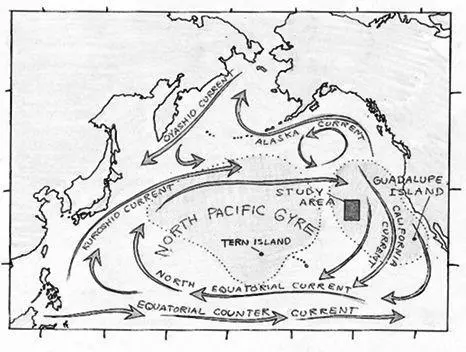

Capt. Charles Moore of Long Beach, California, learned that the day in 1997 when, sailing out of Honolulu, he steered his aluminum-hulled catamaran into a part of the western Pacific he’d always avoided. Sometimes known as the horse latitudes, it is a Texas-sized span of ocean between Hawaii and California rarely plied by sailors because of a perennial, slowly rotating high-pressure vortex of hot equatorial air that inhales wind and never gives it back. Beneath it, the water describes lazy, clockwise whorls toward a depression at the center.

Its correct name is the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, though Moore soon learned that oceanographers had another label for it: the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Captain Moore had wandered into a sump where nearly everything that blows into the water from half the Pacific Rim eventually ends up, spiraling slowly toward a widening horror of industrial excretion. For a week, Moore and his crew found themselves crossing a sea the size of a small continent, covered with floating refuse. It was not unlike an Arctic vessel pushing through chunks of brash ice, except what was bobbing around them was a fright of cups, bottle caps, tangles of fish netting and monofilament line, bits of polystyrene packaging, six-pack rings, spent balloons, filmy scraps of sandwich wrap, and limp plastic bags that defied counting.

Just two years earlier, Moore had retired from his wood-furniture-finishing business. A lifelong surfer, his hair still ungrayed, he’d built himself a boat and settled into what he planned to be a stimulating young retirement. Raised by a sailing father and certified as a captain by the U.S. Coast Guard, he started a volunteer marine environmental monitoring group. After his hellish mid-Pacific encounter with the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, his group ballooned into what is now the Algita Marine Research Foundation, devoted to confronting the flotsam of a half century, since 90 percent of the junk he was seeing was plastic.

What stunned Charles Moore most was learning where it came from. In 1975, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences had estimated that all oceangoing vessels together dumped 8 million pounds of plastic annually. More recent research showed the world’s merchant fleet alone shamelessly tossing around 639,000 plastic containers every day. But littering by all the commercial ships and navies, Moore discovered, amounted to mere polymer crumbs in the ocean compared to what was pouring from the shore.

Map of North Pacific Gyre.

MAP BY VIRGINIA NOREY {1} 1 An original illustration is missing.

The real reason that the world’s landfills weren’t overflowing with plastic, he found, was because most of it ends up in an ocean-fill. After a few years of sampling the North Pacific gyre, Moore concluded that 80 percent of mid-ocean flotsam had originally been discarded on land. It had blown off garbage trucks or out of landfills, spilled from railroad shipping containers and washed down storm drains, sailed down rivers or wafted on the wind, and found its way to this widening gyre.

Читать дальше