Allan Cavinder, a British electrical engineer, had arrived on the island two years earlier, in 1972. He had been taking assignments with a London firm throughout the Middle East, and when he saw Cyprus, he decided to stay. Except for torrid July and August, the island’s weather was mostly mild and spotless. He settled on the northern shore, below mountains where yellow limestone villages lived off the harvests of olive and carob trees, which they exported from an inlet harbor at his town, Kyrenia.

When the war began, he decided to wait it out, figuring correctly that there would be demand for his expertise when it ended. He wouldn’t have predicted the call from the hotel, however. After the Greeks abandoned Varosha, the Turkish Cypriots, rather than let squatters colonize it, decided that the fancy resort would be more valuable as a bargaining chip when negotiations for a permanent reconciliation got underway. So they built a chain-link fence around it, strung barbed wire across the beach, stationed Turkish soldiers to guard it, and posted signs warning everyone else away.

After two years, however, an old Ottoman foundation that owned property that included the northernmost Varosha hotel requested permission to refurbish and reopen it. It was a sensible idea, Cavinder could see. The four-story hotel, to be renamed the Palm Beach, sat far enough back on a shoreline bend that its terrace and beachfront remained sunny through the afternoon. The hotel tower next-door, which had briefly held a Greek machine-gun placement, had collapsed during the Turkish bombing raid, but aside from its rubble everything else Allan Cavinder found when he first entered the zone seemed intact.

Eerily so: he was struck by how quickly humans had abandoned it. The hotel registry was still open to August 1974, when business had suddenly halted. Room keys lay where they’d been tossed on the front desk. Windows facing the sea had been left open, and blowing sand had formed small dunes in the lobby. Flowers had dried in vases; Turkish coffee demitasses and breakfast dishes licked clean by mice were still in place on the table linens.

His task was to bring the air-conditioning system back into service. However, this routine job was proving difficult. The southern, Greek portion of the island had UN recognition as the legitimate Cyprus government, but a separate Turkish state in the north was recognized only by Turkey. With no access to spare parts, an arrangement was made with Turkish troops guarding Varosha to allow Cavinder to quietly cannibalize whatever he needed from the other vacant hotels.

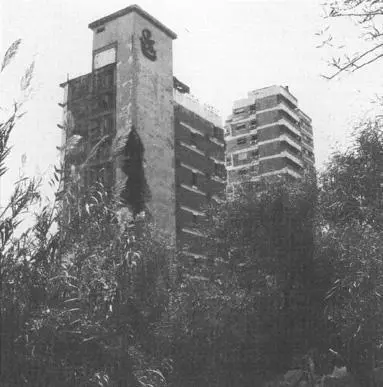

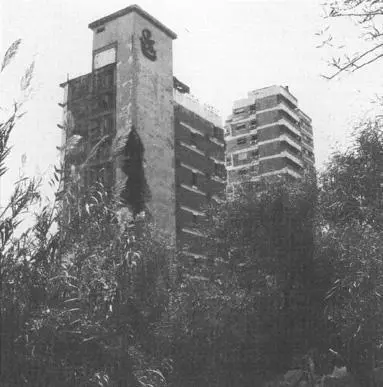

Abandoned hotel, Varosha, Cyprus.

PHOTO BY PETER YATES—IMAGE REPRODUCTION BY ’SOLE STUDIO.

He wandered through the deserted town. About 20,000 people had lived or worked in Varosha. Asphalt and pavement had cracked; he wasn’t surprised to see weeds growing in the deserted streets, but hadn’t expected to see trees already. Australian wattles, a fast-growing acacia species used by hotels for landscaping, were popping out midstreet, some nearly three feet high. Creepers from ornamental succulents snaked out of hotel gardens, crossing roads and climbing tree trunks. Shops still displayed souvenirs and tanning lotion; a Toyota dealership was showing 1974 Corollas and Celicas. Concussions from Turkish air force bombs, Cavinder saw, had exploded plate-glass store windows. Boutique mannequins were half-clothed, their imported fabrics flapping in tattered strips, the dress racks behind them full but deeply dust coated. The canvas of baby prams was likewise torn—he hadn’t expected to see so many left behind. And bicycles.

The honeycombed facades of empty hotels, 10 stories of shattered sliding glass doors opening to seaview balconies now exposed to the elements, had become giant pigeon roosts. Pigeon droppings coated everything. Carob rats nested in hotel rooms, living off Yaffa oranges and lemons from former citrus groves that had been absorbed into Varosha’s landscaping. The bell towers of Greek churches were spattered with the blood and feces of hanging bats.

Sheets of sand blew across avenues and covered floors. What surprised him at first was the general absence of smell, except for a mysterious stench that emanated from hotel swimming pools, most of which were inexplicably drained yet reeked as though filled with cadavers. Around them, the upturned tables and chairs, torn beach umbrellas, and glasses knocked on their sides all spoke of some revelry gone terribly wrong. Cleaning all this up was going to be expensive.

For six months, as he dismantled and rescued air conditioners, industrial washers and dryers, and entire kitchens full of ovens, grills, refrigerators, and freezers, silence pounded at him. It actually hurt his ears, he told his wife. During the year before the war, he’d worked at a British naval base south of town, and would often leave her at a hotel to enjoy a day at the beach. When he picked her up afterward, a dance band would be playing for the German and British tourists. Now, no bands, just the incessant kneading of the sea that no longer soothed. The wind sighing through open windows became a whine. The cooing of pigeons grew deafening. The sheer absence of human voices bouncing off walls was unnerving. He kept listening for Turkish soldiers, who were under instructions to shoot looters. He wasn’t certain how many assigned to patrol knew that he was there legally, or would give him a chance to prove it.

It turned out not to be a problem. He seldom saw any guards. He understood why they would avoid entering such a tomb.

_____

By the time Metin Münir saw Varosha, four years after Allan Cavinder’s reclamation job ended, roofs had collapsed and trees were growing straight out of houses. Münir, one of Turkey’s best-known newspaper columnists, is a Turkish Cypriot who went to Istanbul to study, came home to fight when the troubles began, then returned to Turkey when the troubles kept going on, and on. In 1980, he was the first journalist allowed to enter Varosha for a few hours.

The first thing he noticed was shredded laundry still hanging from clotheslines. What struck him most, though, wasn’t the absence of life but its vibrant presence. With the humans who built Varosha gone, nature was intently recouping it. Varosha, merely 60 miles from Syria and Lebanon, is too balmy for a freeze-thaw cycle, but its pavement was tossed asunder anyway. The wrecking crews weren’t just trees, Münir marveled, but also flowers. Tiny seeds of wild Cyprus cyclamen had wedged into cracks, germinated, and heaved aside entire slabs of cement. Streets now rippled with white cyclamen combs and their pretty, variegated leaves.

“You understand,” Münir wrote his readers back in Turkey, “just what the Taoists mean when say they say that soft is stronger than hard.”

Two more decades passed. The millennium turned, and kept going. Once, Turkish Cypriots had bet that Varosha, too valuable to lose, would force the Greeks to the bargaining table. Neither side had dreamed that, 30-plus years later, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus would still exist, severed not only from the Greek Republic of Cyprus but from the world, still a pariah nation to all except Turkey. Even the UN Peacekeeping Force was exactly where it was in 1974, still listlessly patrolling the Green Line, occasionally waxing a pair of still-impounded, still-new 1974 Toyotas.

Nothing has changed except Varosha, which is entering advanced stages of decay. Its encircling fence and barbed wire are now uniformly rusted, but there is nothing left to protect but ghosts. An occasional Coca Cola sign and broadsides posting nightclubs’ cover charges hang on doorways that haven’t seen customers in more than three decades, and now never will again. Casement windows have flapped and stayed open, their pocked frames empty of glass. Fallen limestone facing lies in pieces. Hunks of wall have dropped from buildings to reveal empty rooms, their furniture long ago somehow spirited away. Paint has dulled; the underlying plaster, where it remains, has yellowed to muted patinas. Where it doesn’t, brick-shaped gaps show where mortar has already dissolved.

Читать дальше