R: You go by cubic millimeters. I would say this right off the bat—Anybody with burns, the red count goes down after a while, and the white count may go down, too, just from an ordinary burn. I can’t get too excited about that.

G: We are not bothered a bit, excepting for—what they are trying to do is create sympathy. The sad part of it all is that an American started them off.

R: Let me look it up and I’ll give you some straight dope on it.

G: This is the kind of thing that hurts us—“The Japanese, who were reported today by Tokyo radio, to have died mysteriously a few days after the atomic bomb blast, probably were the victims of a phenomenon which is well known in the great radiation laboratories of America.” That, of course, is what does us the damage.

R: I would say this: You will have to get some big-wig to put a counter-statement in the paper.

Source: National Security Archive

Appendix 2

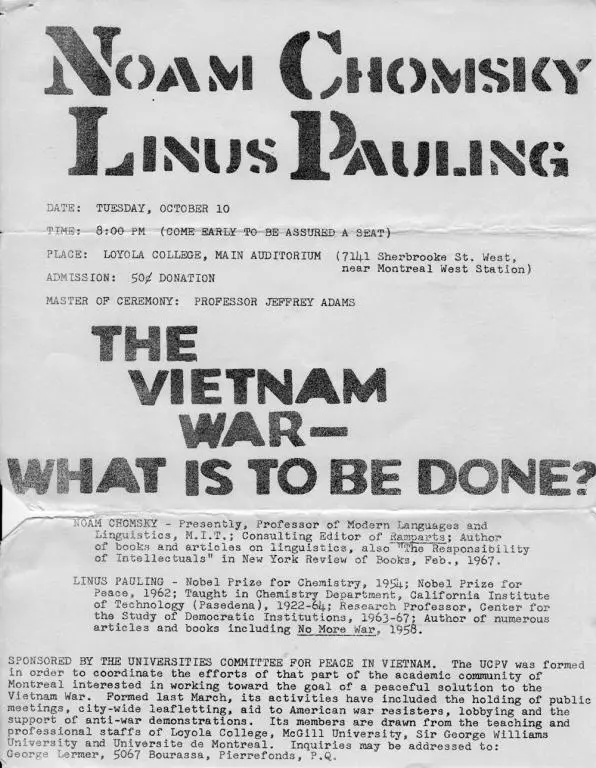

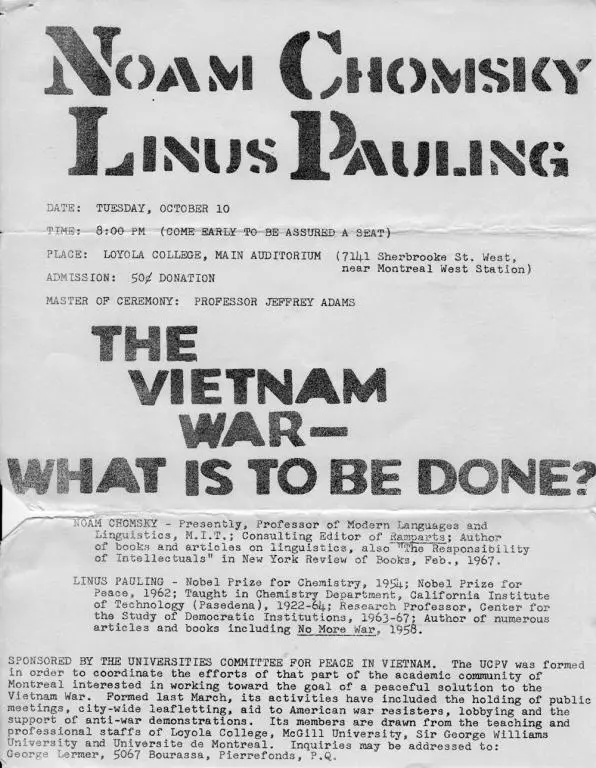

Flyer for UCPV Event, October 10, 1967

This event, hosted by the academic community of Montreal, demonstrates the transnational involvement in resistance to the war in Vietnam. It was one of several events where Chomsky and Pauling were coparticipants.

Noam Chomsky

Linus Pauling

DATE: TUESDAY, OCTOBER 10

TIME: 8:00 PM (COME EARLY TO BE ASSURED A SEAT)

PLACE: LOYOLA COLLEGE, MAIN AUDITORIUM (7141 Sherbrooke St. West, near Montreal West Station)

ADMISSION: 50¢ DONATION

MASTER OF CEREMONY: PROFESSOR JEFFREY ADAMS

THE VIETNAM WAR—WHAT IS TO BE DONE?

NOAM CHOMSKY - Presently, Professor of Modern Languages and Linguistics, M.I.T.; Consulting Editor of Ramparts ; Author of books and articles on linguistics, also “The Responsibility of Intellectuals” in New York Review of Books, Feb., 1967.

LINUS PAULING - Nobel Prize for Chemistry, 1954; Nobel Prize for Peace, 1962; Taught in Chemistry Department, California Institute of Technology (Pasadena), 1922–64; Research Professor, Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions, 1963–67; Author of numerous articles and books including No More War , 1958.

SPONSORED BY THE UNIVERSITIES COMMITTEE FOR PEACE IN VIETNAM. The UCPV was formed in order to coordinate the efforts of that part of the academic community of Montreal interested in working toward the goal of a peaceful solution to the Vietnam War. Formed last March, its activities have included the holding of public meetings, city-wide leafletting, aid to American war resisters, lobbying and the support of anti-war demonstrations. Its members are drawn from the teaching and professional staffs of Loyola College, McGill University, Sir George Williams University and Universite de Montreal. Inquiries may be addressed to: George Lermer, 5067 Bourassa, Pierrefonds, P.Q.

Source: Special Collections & Archives Research Center, Oregon State University

Appendix 3

Scientists Condemn the Destruction of Crops in Vietnam, January 21, 1966

In response to a front-page article in the New York Times, “U.S. Spray Planes Destroy Rice in Vietcong Territory,” a small group circulated a petition denouncing the destruction of food crops. The petition classifies the activity as indiscriminate chemical warfare and warns such practices would encourage other countries to employ similar tactics. Almost a year later, more than five thousand scientists signed a similar petition calling for a ban on chemical and biological weapons. One of the lead authors of both petitions, Matthew S. Meselson, studied with Linus Pauling at Caltech.

The use of crop-destroying chemicals by American forces in Vietnam was condemned this week in a statement by 29 scientists and physicians from Harvard, M.I.T., and several nearby institutions.

The statement made reference to a New York Times dispatch which reported that, as part of a “large program of ‘food denial’ to the Vietcong,” U.S. aircraft have been spraying rice crops with a “commercial weedkiller, identical with a popular brand that many Americans spray on their lawns.” The Times report added that “it is not poisonous, and officials say that any food that survives its deadening touch will not be toxic or unpalatable.”

The areas involved, according to the report, cover only a “small fraction—50,000 to 70,000 acres—of the more than eight million acres of cultivated land in South Vietnam.” The program was reported “aimed only at relatively small areas of major military importance where the guerillas grow their own food or where the population is willingly committed to their cause.” “Experience has shown,” the Times stated, “that when the chemical is applied during the growing season, before rice and other food plants are ripe, it will destroy 60 to 90 percent of the crop.”

John Edsall, Harvard professor of biochemistry, served as spokesman for the protesting group. The statement follows.

“We emphatically condemn the use of chemical agents for the destruction of crops, by United States forces in Vietnam as recently reported in the New York Times of Tuesday, 21 December 1965. Even if it can be shown that chemicals are not toxic to man, such tactics are barbarous because they are indiscriminate; they represent an attack on the entire population of the region where the crops are destroyed, combatants and non-combatants alike. In the crisis of World War II, in which the direct threat to our country was far greater than any arising in Vietnam today, our government firmly resisted any proposals to employ chemical or biological warfare against our enemies. The fact that we are now resorting to such methods shows a shocking deterioration of our moral standards. These attacks are also abhorrent to the general standards of civilized mankind, and their use will earn us hatred throughout Asia and elsewhere.

“Such attacks serve moreover as a precedent for the use of similar but even more dangerous chemical agents against our allies and ourselves. Chemical warfare is cheap; small countries can practice it effectively against us and will probably do so if we lead the way. In the long run the use of such weapons by the United States is thus a threat, not an asset, to our national security.

“We urge the President to proclaim publicly that the use of such chemical weapons by our armed forces is forbidden, and to oppose their use by the South Vietnamese or any of our allies.”

The signers of the statement were as follows.

Harvard : John Edsall, Bernard Davis, Keith R. Porter, George Gaylord Simpson, Matthew S. Meselson, George Wald, Stephen Kuffler, Mahlon B. Hoagland, Eugene P. Kennedy, David H. Hubel, Warren Gold, Sanford Gifford, Peter Reich, Robert Goldwyn, Jack Clark, and Bernard Lown.

Massachusetts General Hospital : Victor W. Sidel, Stanley Cobb, and Herbert M. Kalckar.

M.I.T. : Alexander Rich, Patrick D. Wall, and Charles D. Coryell.

Brandeis : Nathan O. Kapland and William P. Jencks.

Amherst : Henry T. Yost.

Dartmouth : Peter H. von Hippel.

Tufts : Charles E. Magraw.

Also, Albert Szent-Györgyi, director of the Institute for Muscle Research, Woods Hole, and Hudson Hoagland, director of the Worcester Institute of Experimental Biology.

Source: Science

Appendix 4

Nelson Anjain’s Open Letter to Robert Conard, April 9, 1975

From 1946 to 1958, the US Nuclear Weapons Testing Program conducted sixty-seven nuclear detonations in the Marshall Islands. In 1956, Merril Eisenbud, director of the AEC Health and Safety Laboratory, outlined the benefits of studying a Marshallese population inhabiting an environment known to be radioactively contaminated: “[N]ow that Island is safe to live on but is by far the most contaminated place in the world and it will be very interesting to go back and get good environmental data, … While it is true that these people do not live, I would say, the way Westerners do, civilized people, it is nevertheless also true that these people are more like us than the mice.”

Читать дальше