That is how I came to meet Tom. I called him up right away and asked whether he would like to participate in a study. Although initially shy and reticent in his mannerisms, Tom soon became eager to participate in our experiment. I was careful not to tell him what we hoped to find, so as not to bias his responses. Even though he was distressed by “itching” and painful sensations in his phantom fingers, he was cheerful, apparently pleased that he had survived the accident.

With Tom seated comfortably in my basement laboratory, I placed a blindfold over his eyes because I didn’t want him to see where I was touching him. Then I took an ordinary Q-tip and started stroking various parts of his body surface, asking him to tell me where he felt the sensations. (My graduate student, who was watching, thought I was crazy.)

I swabbed his cheek. “What do you feel?”

“You are touching my cheek.”

“Anything else?”

“Hey, you know it’s funny”, said Tom. “You’re touching my missing thumb, my phantom thumb.”

I moved the Q-tip to his upper lip. “How about here?”

“You’re touching my index finger. And my upper lip.”

“Really? Are you sure?”

“Yes. I can feel it both places.”

“How about here?” I stroked his lower jaw with the swab.

“That’s my missing pinkie.”

I soon found a complete map of Tom’s phantom hand on his face! I realized that what I was seeing was perhaps a direct perceptual correlate of the remapping that Tim Pons had seen in his monkeys. For there is no other way of explaining why touching an area so far away from the stump namely, the face should generate sensations in the phantom hand; the secret lies in the peculiar mapping of body parts in the brain, with the face lying right beside the hand. 7

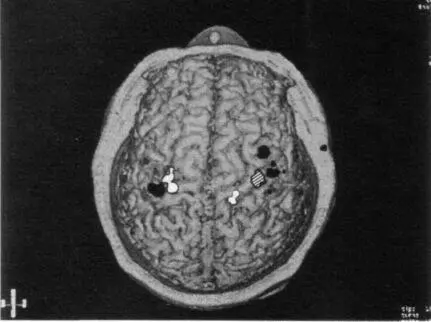

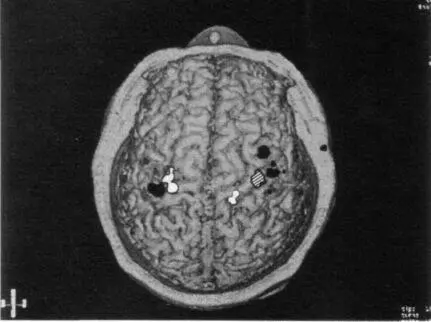

I continued this procedure until I had explored Tom’s entire body surface. When I touched his chest, right shoulder, right leg or lower back, he felt sensations only in those places and not in the phantom. But I also found a second, beautifully laid out “map” of his missing hand tucked onto his left upper arm a few inches above the line of amputation (Figure 2.2). Stroking the skin surface on this second map also evoked precisely localized sensations on the individual fingers: Touch here and he says, “Oh, that’s my thumb”, and so on.

Why were there two maps instead of just one? If you look again at the Penfield map, you’ll see that the hand area in the brain is flanked below by the face area and above by the upper arm and shoulder area. Input from Tom’s hand area was lost after the amputation, and consequently, the sensory fibers originating from Tom’s face which normally activate only the face area in his cortex now invaded the vacated territory of the hand and began to drive the cells there. Therefore, when I touched Tom’s face, he also felt sensations in his phantom hand. But if the invasion of the hand cortex also results from sensory fibers that normally innervate the brain region above the hand cortex (that is, fibers that originate in the upper arm and shoulder), then touching points on the upper arm should also evoke sensations in the phantom hand. And indeed I was able to map out these points on the arm above Tom’s stump. So, this sort of arrangement is precisely what one would expect: One cluster of points on the face that evoke sensations in the phantom and a second cluster on the upper arm, corresponding to the two body parts that are represented on either side (above and below) of the hand representation in the brain. 8

Figure 2.2 Points on the body surface that yielded referred sensations in the phantom hand (this patient’s left arm had been amputated years prior to our testing him). Notice that there is a complete map of all the fingers (labeled 1 to 5) on the face and a second map on the upper arm. The input from these two patches of skin is now apparently activating the hand territory of the brain (either in the thalamus or in the cortex). So when these points are touched, the sensations are felt to arise from the missing hand as well.

It’s not often in science (especially neurology) that you can make a simple prediction like this and confirm it with a few minutes of exploration using a Q-tip. The existence of two clusters of points suggests strongly that remapping of the kind seen in Pons’s monkeys also occurs in the human brain. But there was still a nagging doubt: How can we be sure that such changes are actually taking place — that the map is really changing in people like Tom? To obtain more direct proof, we took advantage of a modern neuroimaging technique called magnetoencephalography (MEG), which relies on the principle that if you touch different body parts, the localized electrical activity evoked in the Penfield map can be measured as changes in magnetic fields on the scalp. The major advantage of the technique is that it is noninvasive; one does not have to open the patient’s scalp to peer inside the brain.

Using MEG, it is relatively easy in just a two-hour session to map out the entire body surface on the brain surface of any person willing to sit under the magnet. Not surprisingly, the map that results is quite similar to the original Penfield homunculus map, and there is very little variation from person to person in the gross layout of the map. When we conducted MEGs on four arm amputees, however, we found that the maps had changed over large distances, just as we had predicted. For example, a glance at Figure 2.3 reveals that the hand area (hatched) is missing in the right hemisphere and has been invaded by the sensory input from the face (in white) and upper arm (in gray). These observations, which I made in collaboration with a medical student, Tony Yang, and the neurologists Chris Gallen and Floyd Bloom, were in fact the first direct demonstration that such large-scale changes in the organization of the brain could occur in adult humans.

The implications are staggering. First and foremost, they suggest that brain maps can change, sometimes with astonishing rapidity. This finding flatly contradicts one of the most widely accepted dogmas in neurology — the fixed nature of connections in the adult human brain. It had always been assumed that once this circuitry, including the Penfield map, has been laid down in fetal life or in early infancy, there is very little one can do to modify it in adulthood. Indeed, this presumed absence of plasticity in the adult brain is often invoked to explain why there is so little recovery of function after brain injury and why neurological ailments are so notoriously difficult to treat. But the evidence from Tom shows — contrary to what is taught in textbooks — that new, highly precise and functionally effective pathways can emerge in the adult brain as early as four weeks after injury. It certainly doesn’t follow that revolutionary new treatments for neurological syndromes will emerge from this discovery right away, but it does provide some grounds for optimism.

Second, the findings may help explain the very existence of phantom limbs. The most popular medical explanation, noted earlier, is that nerves that once supplied the hand begin to innervate the stump. Moreover, these frayed nerve endings form little clumps of scar tissue called neuromas, which can be very painful. When neuromas are irritated, the theory goes, they send impulses back to the original hand area in the brain so that the brain is “fooled” into thinking the hand is still there: hence the phantom limb and the notion that the accompanying pain arises because the neuromas are painful.

Читать дальше