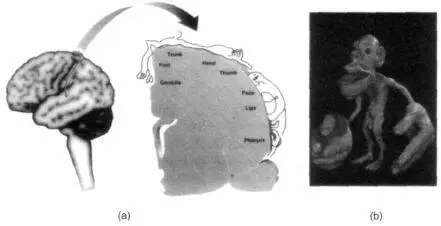

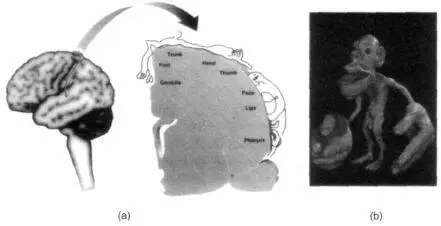

Of the many strange images that have remained with me from my medical school days, perhaps none is more vivid than that of the deformed little man you see in Figure 2.1 draped across the surface of the cerebral cortex — the so-called Penfield homunculus. The homunculus is the artist’s whimsical depiction of the manner in which different points on the body surface are mapped onto the surface of the brain — the grotesquely deformed features are an attempt to indicate that certain body parts such as the lips and tongue are grossly overrepresented.

The map was drawn from information gleaned from real human brains. During the 1940s and 1950s, the brilliant Canadian neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield performed extensive brain surgeries on patients under local anesthetic (there are no pain receptors in the brain, even though it is a mass of nerve tissue). Often, much of the brain was exposed during the operation and Penfield seized this opportunity to do experiments that had never been tried before. He stimulated specific regions of the patients’ brains with an electrode and simply asked them what they felt. All kinds of sensations, images, and even memories were elicited by the electrode and the areas of the brain that were responsible could be mapped.

Among other things, Penfield found a narrow strip running from top to bottom down both sides of the brain where his electrode produced sensations localized in various parts of the body. Up at the top of the brain, in the crevice that separates the two hemispheres, electrical stimulation elicited sensations in the genitals. Nearby stimuli evoked sensations in the feet. As Penfield followed this strip down from the top of the brain, he discovered areas that receive sensations from the legs and trunk, from the hand (a large region with a very prominent representation of the thumb), the face, the lips and finally the thorax and voicebox. This “sensory homunculus”, as it is now called, forms a greatly distorted representation of the body on the surface of the brain, with the parts that are particularly important taking up disproportionately large areas. For example, the area involved with the lips or with the fingers takes up as much space as the area involved with the entire trunk of the body. This is presumably because your lips and fingers are highly sensitive to touch and are capable of very fine discrimination, whereas your trunk is considerably less sensitive, requiring less cortical space. For the most part, the map is orderly though upside down: The foot is represented at the top and the outstretched arms are at the bottom. However, upon close examination, you will see that the map is not entirely continuous. The face is not near the neck, where it should be, but is below the hand. The genitals, instead of being between the thighs, are located below the foot. 4

Figure 2.1 (a) The representation of the body surface on the surface of the human brain (as discovered by Wilder Penfield) behind the central sulcus. There are many such maps, but for clarity only one is shown here.

The homunculus (“little man”) is upside down for the most part, and his feet are tucked onto the medial surface (inner surface) of the parietal lobe near the very top, whereas the face is down near the bottom of the outer surface. The face and hand occupy a disproportionately large share of the map. Notice, also that the face area is below the hand area instead of being where it should — near the neck and that the genitals are represented below the foot. Could this provide an anatomical explanation of foot fetishes? (b) A whimsical three-dimensional model of the Penfield homunculus — the little man in the brain depicting the representation of body parts. Notice the gross overrepresentation of mouth and hands. Reprinted with permission from the British Museum, London.

These areas can be mapped out with even greater precision in other animals, particularly in monkeys. The researcher inserts a long thin needle made of steel or tungsten into the monkey’s somatosensory cortex — the strip of brain tissue described earlier. If the needle tip comes to lie right next to the cell body of a neuron and if that neuron is active, it will generate tiny electrical currents that are picked up by the needle electrode and amplified. The signal can be displayed on an oscilloscope, making it possible to monitor the activity of that neuron.

For example, if you put an electrode into the monkey’s somatosensory cortex and touch the monkey on a specific part of its body, the cell will fire. Each cell has its territory on the body surface — its own small patch of skin, so to speak — to which it responds. We call this the cell’s receptive field. A map of the entire body surface exists in the brain, with each half of the body mapped onto the opposite side of the brain.

While animals are logical experimental subjects in which to examine the detailed structure and function of the brain’s sensory regions, they have one obvious problem: Monkeys can’t talk. Therefore, they cannot tell the experimenter, as Penfield’s patients could, what they are feeling. Thus a large and important dimension is lost when animals are used in such experiments.

But despite this obvious limitation, a great deal can be learned by doing the right kinds of experiments. For instance, as we’ve noted, one important question concerns nature versus nurture: Are these body maps on the surface of the brain fixed, or can they change with experience as we grow from newborns to infancy, through adolescence and into old age? And even if the maps are already there at birth, to what extent can they be modified in the adult? 5

It was these questions that prompted Tim Pons and his colleagues to embark on their research. Their strategy was to record signals from the brains of monkeys who had undergone dorsal rhizotomy — a procedure in which all the nerve fibers carrying sensory information from one arm into the spinal cord are completely severed. 6 Eleven years after the surgery, they anesthetized the animals, opened their skulls and recorded from the somatosensory map. Since the monkey’s paralyzed arm was not sending messages to the brain, you would not expect to record any signals when you touch the monkey’s useless hand and record from the “hand area” of the brain. There should be a big patch of silent cortex corresponding to the affected hand.

Indeed, when the researchers stroked the useless hand, there was no activity in this region. But to their amazement they found that when they touched the monkey’s face, the cells in the brain corresponding to the “dead” hand started firing vigorously. (So did cells corresponding to the face, but those were expected to fire.) It appeared that sensory information from the monkey’s face not only went to the face area of the cortex, as it would in a normal animal, but it had also invaded the territory of the paralyzed hand!

The implications of this finding are astonishing: It means that you can change the map; you can alter the brain circuitry of an adult animal, and connections can be modified over distances spanning a centimeter or more.

Upon reading Pons’s paper, I thought, “My God! Might this be an explanation for phantom limbs?” What did the monkey actually “feel” when its face was being stroked? Since its “hand” cortex was also being excited, did it perceive sensations as arising from the useless hand as well as the face? Or would it use higher brain centers to reinterpret the sensations correctly as arising from the face alone? The monkey of course was silent on the subject.

It takes years to train a monkey to carry out even very simple tasks, let alone signal what part of its body is being touched. Then it occurred to me that you don’t have to use a monkey. Why not answer the same question by touching the face of a human patient who has lost an arm? I telephoned my colleagues Dr. Mark Johnson and Dr. Rita Finkelstein in orthopedic surgery and asked, “Do you have any patients who have recently lost an arm?”

Читать дальше