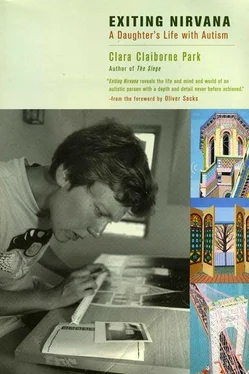

Clara Park - Exiting Nirvana

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Clara Park - Exiting Nirvana» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: Психология, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Exiting Nirvana

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:0-316-69117-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Exiting Nirvana: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Exiting Nirvana»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

All illustrations are by Jessy Park.

Exiting Nirvana — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Exiting Nirvana», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It was there. The vigorous intelligence her siblings were putting into exploring history, learning Tibetan, writing novels, and negotiating their lives, in Jessy was streaming into this one channel.

Jessy reached everywhere for systems in those days. Together we looked at a Tintin book; Tintin, lost in the desert, sends a message. But what she took from the story was not adventure but a system. Tintin sent us to the encyclopedia; days later I found a sheet on which she had, accurately and without book, written out the full Morse code. I started her on the piano; I was surprised, though I shouldn’t have been, at how fast she learned musical notation. But these experiences, meant to enrich, remained void of content. Jessy had no interest in tapping out a message, and though she had an excellent ear, she took no pleasure in making music. Systems were enjoyed for their formal qualities, not their use. Someone gave her a junior-high dictionary, each word briefly defined and illustrated by a simple sentence, perfect for a beginning reader. She spent hours poring over it, and we rejoiced. But what was she doing? Searching out regularities, discovering the few that English can offer. She thought about them, talked about them, wrote them down. Elf, elves; self, selves; shelf, shelves; half, halves; calf, calves; knife, knives; wife, wives; hoof, hooves; leaf, leaves; sheaf, sheaves… «How about ‘reef, reeves’?» she asked. «How about ‘roof, rooves’?» The dictionary was crammed with meanings, gateways to knowledge and communication. We watched as Jessy, surrounded by words, now at last hearing them, seeing them, even reading them, drained them of meaning, to be absorbed into her world of abstract formalisms.

Language, of course, resists abstraction; if it didn’t we’d all be speaking Esperanto. Jessy picked up a ski resort’s chart of weather conditions. Cold, Very Cold, Extreme Cold, Bitter Cold; a snowy universe reduced to four categories. Unfettered by meaning, Jessy could extrapolate, and did. Her chart read Good, Very Good, Extreme Good — and Bitter Good.

Maps, like charts, are formalisms. Jessy mapped her neighborhood, she mapped our journey route by route, all the way from western Massachusetts to Rhode Island. She diagrammed floor plans of familiar buildings. Systems ordered space; they ordered time as well. Jessy liked printed schedules, calendars, clocks. Telling time was so easy for her that we wondered the more at the effort it took to nudge her through familiar words about familiar subjects. Reading was hard; it demanded more than an ability — even a preternatural ability — to discriminate patterns of letters. It insisted on meaning, and meaning offered Jessy no rewards. But what joyous energy she poured into locating «sheaf» and «sheaves»!

Shortly after her fourteenth birthday, Jessy made a book. There was nothing remarkable about that; following on our early work with picture communication, Jessy had been making picture books for years — rapid scrawls, uncolored, reflecting TV cartoons, children’s stories, and the rituals of her own daily life. This, however, was not a picture book. It contained neither drawings nor sequential narrative. Rather, it was a celebration of the trans-formations of a word.

The book was a thing of beauty, a theme and variations, four words in three colors: SING, SANG, SUNG, and SONG (see page 63). It was also a finely organized system. It was not, however, as remote from daily life as it appeared. Jessy had an additional source of inspiration — a bag of cookies. How she must have scrutinized it, alone in her room, to note the possibilities of its three shades of coral, its corresponding greens, its contrasting white! Never mind crayons; here, in this bag, were her materials. Patiently she snipped the colors into bits, 208 in all. Each word had its own page, the three-inch letters formed of the snips, SING and SANG in coral, a different shade for each letter, SUNG and SONG in green to correspond. Except for the four final G’s; for these she had reserved the white snips, backing them with coral and green cutouts so they would show up on the white pages. Nor had she forgotten the cookies; they were part of the pleasure. Neatly she cut out their labels, Assorted, Cashew, Almond Crescent, Chocolate Chip; these too became part of the ensemble. Still she was not done. Logic propelled her forward; to the fifth page she taped swatches of her base colors; to the sixth, finely balanced collages in all six shades of coral and green. The seventh page she had reserved for a larger, climactic collage in — what else? — white on white.

The whole was strangely modern, even postmodern, except that Jessy had no idea of what such terms might mean. When I asked her, on a hunch, «What is the name of that art?» she didn’t say «Collage», as I thought she might. Her answer was both specific and accurate: «Those are the cookie art».

I can describe the cookie art, as I can describe much else that we did together or that Jessy later told me about. But the system of systems, the supersystem that in those days eclipsed every other, reflected and conditioned the whole of her emotional experience, encompassed everything she most cared about — that is not mine to describe. I learned about it second-hand. It is time to pay tribute, however inadequately, to the many others who shared devotedly, year after year, the enterprise of helping Jessy grow. I long ago lost count of them; besides the members of her own family there have been more than fifty. It wasn’t I who taught her to tie her shoes. It wasn’t I who taught her to ride a bicycle, to knit, to weave, to draw. And it wasn’t I who worked out the organizing principles of Jessy’s supreme, her most complex, creation. An eighteen-year-old mathematics student at Williams College figured it out, helped in the write-up by Jessy’s father, and it is right that work I did not and could not do should be told in their voices. So I quote, and at length, from David Park and Philip Youderian’s article «Light and Number: Ordering Principles in the World of an Autistic Child». Imagine, then, Jessy as she was at thirteen:

[Jessy] listens to hard rock with an expression of the purest joy, rocking in her rocking chair, putting her hands over her ears when it is too much to bear, for this is the music of o clouds and 4 doors… No clouds at all, the sky the radiant image of a pleasure so intense that to bring it down to a really bearable level would, she shows us, require 4 closed doors between her and the phonograph. It is, she explains, «too good», but she can bear it for a while. The music changes; the rapture abates by one degree: 1 cloud, 3 doors. The classics, most of them, rate 2 clouds and 2 doors; andante espressivo brings protests, 3 clouds and 1 door; and worst of all is a spoken record, 4 and o. The sum of clouds and doors is always 4, and. even the sun loses some of its rays when the music is not of the best.

[Jessy] always watches the phases of the moon and knows where it is in its cycle. On the nights following a full moon, it rises outside [her] window and stays for several hours partly visible behind a large tree. Behind [her] door there is intense excitement, the sound of running feet and little cries of joy. [Jessy] is looking at it — she will not say its name but refers to «something behind the tree» — running from window to window to see the light travel behind the branches and the shadows creep across the grass. The shadow cast by a house standing in the light of the full moon is the most exciting and beautiful sight in the world, and in these long evenings everything depends on there being no clouds to spoil the pleasure. If the moon is obscured, [Jessy] lies in bed and cries her tearless autistic cry. The moon is the number 7, and so is the sun, and so, apparently, is a cloudless sky.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Exiting Nirvana»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Exiting Nirvana» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Exiting Nirvana» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Майкл Азеррад - Come as you are - история Nirvana, рассказанная Куртом Кобейном и записанная Майклом Азеррадом [litres]](/books/392533/majkl-azerrad-come-as-you-are-istoriya-nirvana-ra-thumb.webp)

![Эверетт Тру - Nirvana - Правдивая история [litres]](/books/399241/everett-tru-nirvana-pravdivaya-istoriya-litres-thumb.webp)