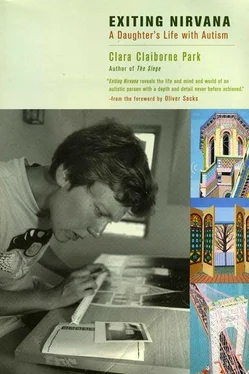

Clara Park - Exiting Nirvana

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Clara Park - Exiting Nirvana» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: Психология, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Exiting Nirvana

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:0-316-69117-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Exiting Nirvana: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Exiting Nirvana»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

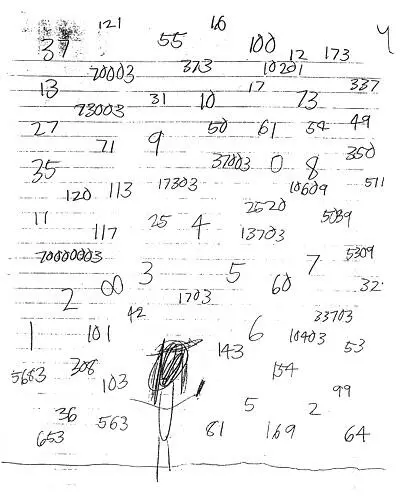

All illustrations are by Jessy Park.

Exiting Nirvana — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Exiting Nirvana», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Jessy at a number-filled blackboard

In its early stages, when Jessy was eight, numbers didn’t seem particularly interesting for her or for us. They were something she could do, that was all, and with a child who did so little, that was enough. So there we were, she and I, day after day, down on the floor, crayons at the ready. I’m a bit bored, more than a bit; I’m drawing row after row, sheet after sheet, of triangles for her to count then color, the inspiration the Halloween corn candies that like other candies were such an important part of her small universe. There was no pressure; there didn’t need to be. Jessy liked repetition, she liked counting, she liked counting some more. She liked coloring with her mother, both of us fixed on this simple, unchallenging activity. She liked it when I added another triangle and showed her the plus sign. I was teaching notation, not ideas; I knew that. But unawares I was also teaching something more important. Shared attention! The phrase, and the research behind it, was far in the future. But here we were, together on the floor. Another day, another sheet.

Jessy had been in nursery school four years when the nice teachers had to tell me they couldn’t keep her among the little ones any longer. After months of corn candies, she could do more than keep track of missing washcloths, she could add and subtract on paper. Her numbers were scrawly and her 5’s turned backwards, but her answers were right. So when September came I took her, wordless and unresponsive, to the principal of our local elementary school and showed him her numbers. He didn’t bother with politeness — he thought they were all done by rote and said so. He didn’t have to explain the subtext: an intellectual mother pushing an incapable child beyond what she could possibly accomplish. Jessy lasted only eight weeks in the special class. There was no «right to education» for the handicapped in those days. [23] For more on Jessy’s slow road to a full school day, see C. C. Park, „Elly and the Right to Education“, in Contemporary Issues in Special Education, R. E. Schmid, J. Moneypenny, and R. Johnston, eds. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1977), pp. 34–37.

But to push Jessy beyond where she was ready to go was not what the intellectual mother could do, even if she had wanted to. Words must come before numbers, I thought, as they do in life — in normally developing life. I need not hurry my daughter into what came naturally. So we moved into multiplication and division slowly. Another year. More sheets. Corn candies were succeeded by the heart-candies of Valentine’s Day, the kind that carry a word or two like LOVE or KISS ME, so we could also work toward words. More rows: times tables, is and 2’s and 3’s, then more rapidly (it was all so easy) up to 10, as the operations in her head were made visible, then assumed their conventional written form: +, -, X, +. So why not fractions? I remembered how hard they’d been for me, but I was not Jessy. Hearts turned to circles, to rows and rows of pie charts, ever more complex. So why not one step further, letters for numbers, the beginnings of algebra? Jessy might not know the right way to talk about a baby, but she had no problem with that. It was as obvious to her that a + a = 2a, a X a = a 2, a — a = o, as that 1 + 1 = 2. As for —1, wasn’t it equally obvious that that was what you’d have if you took 1 away from zero? So there it was, all in place: «When I ten, that minus one!»

It’s not surprising that so many autistic people are more at home with numbers than babies. Mathematics too is a language, but a language that is predictable, logical, rule-governed, blessedly abstracted from shifting social contexts. Teaching Jessy the ways of numbers was like providing a natural athlete with a ball and bat. Whereas words… I wrote words on the candies — NUT, CUT, HUT (a lesson in phonics), common words, her own name — and Jessy would reluctantly read them. But then she’d veer away, transforming them into nonsense: JESSY, JASSY, JISSY, JKSSY, KESS. (Still, she’d inferred the rule. «Throw away N», she told me. «Can’t say NUT. Just say UT, yes!»)

We kept on with candies and circles till Jessy was past eleven. She was used to them, and I wanted to ensure that the abstract operations stayed meaningful, anchored in things that could actually be counted. But it became clear Jessy no longer needed them, if indeed she ever had. As with the washcloths, she had no trouble with real-life calculations. When she was nine, late in 1967, it occurred to me to ask her, «How old will you be in 1975?» took her less than three seconds to answer, «Seventeen». Numbers had become more than an acceptable pastime; she grew enthusiastic as two-digit multiplication and long division opened up new possibilities. «Multiply?» she’d ask. «Fractions?» After two years of pie charts she summed up her progress, proudly remembering, «When a little girl, can’t reduce to lowest terms!»

Numbers, good in the abstract, expressed the world. And they expressed her. As her twelfth birthday approached, we saw some very unusual numbers: || 351/365, || 71/73, || 359/365. What could they mean? Then we understood; with characteristic exactitude, Jessy was calculating her age. Two weeks short of her birthday: 365 — 14 = 351 days. One week short: 359 days. And ten days? 71/73? That’s what you get when you reduce 355/365 to lowest terms!

Age eleven was when Jessy took off on her own. Now she made her own sheets; she no longer needed a mathematical companion, though a resourceful helper taught her to calculate areas. Megan drew diagrams and Jessy solved the problems handily; she understood their connection to the real world. But the world that was most real to her was not that of our everyday bread-and-butter problems. With the necessary notations and operations in place, numbers, not words, became Jessy’s primary expressive instrument.

We can’t know how great a part circumstances played in Jessy’s annus mirabilis. For we were not at home in her familiar house full of built-in activities; as once before, when she was four, her father was on sabbatical. We were living ten floors up in a small apartment outside Paris. No toys — not that Jessy played with toys much — nothing but paper, pencils, and a typewriter. In the cold, cloudy spring, only the activities we could think up. Prodigiously inventive, Megan lured Jessy into reading, typing questions to which Jessy typed out answers in a progressive dialogue. She typed out, in words, all the numbers from i to 100; it turned out she could spell better than we knew. The typewriter was good for numbers; with Megan she converted fractions to percents and solved simple equations. But Jessy could not be constantly accompanied. Alone in her own world she pursued different calculations.

Clocks became fascinating when she learned that the French numbered time not in twelve hours but in twenty-four. She drew a ten-hour clock, a twelve-hour clock, a fourteen-hour clock, sixteen-, eighteen-, twenty-four-, and thirty-six-hour clocks. She converted hours to minutes, minutes to seconds; surviving sheets record that 3600 seconds = 60 minutes = 1 hour. Carefully she drew in each second. Time was now something to play with. Fractional conversions became so rapid as to seem intuitive: 49 hours = 2 1/24 days. Soon she was mapping space as well as time: 7 1/2 inches = 5/8 foot.

And hour after hour she multiplied and divided. There were no calculators then. I couldn’t keep all the sheets of paper she consumed, and Jessy didn’t want them. Once they were done, she’d internalized her discoveries, 51 X 51, 52 X 52, 53 X 53, and on and on. Even I could see what she was up to: determining squares, then cubes, then higher and higher powers. And what can be multiplied can be divided; her long division became more and more bizarre as she searched out larger primes and identified more factors. She liked the number 60; it was handy for clocks. I kept the sheet that said it was divisible twelve ways. But that was just the beginning. Months later another sheet recorded that 26082 was divisible by 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 14, 18, 21, 23, 27, 42, 46, 54, 63, 69, 81, 126, 138, 161, 162, 189, 207, 322, 378, 414, 483, 567, 621, 966, 1134, 1242, 1449, 1863, 2898. There the numbers stopped. Did she finish the series somewhere else?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Exiting Nirvana»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Exiting Nirvana» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Exiting Nirvana» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Майкл Азеррад - Come as you are - история Nirvana, рассказанная Куртом Кобейном и записанная Майклом Азеррадом [litres]](/books/392533/majkl-azerrad-come-as-you-are-istoriya-nirvana-ra-thumb.webp)

![Эверетт Тру - Nirvana - Правдивая история [litres]](/books/399241/everett-tru-nirvana-pravdivaya-istoriya-litres-thumb.webp)