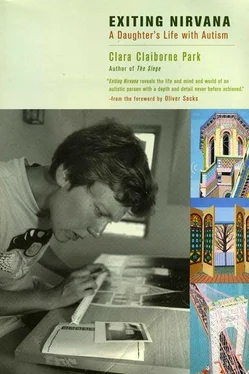

Clara Park - Exiting Nirvana

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Clara Park - Exiting Nirvana» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: Психология, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Exiting Nirvana

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:0-316-69117-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Exiting Nirvana: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Exiting Nirvana»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

All illustrations are by Jessy Park.

Exiting Nirvana — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Exiting Nirvana», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

And there are, or were, the mumbles, dark, ominous, existing in a no-man’s-land between verbalization and pure sound, as involuntary as her furious snaps. The snaps, at least, are interpretable; though „Why do you ask me that?“ expects no answer, I can hear the meaning beneath: „I’m really angry when you ask that kind of question“. But the mumbles were subverbal, idiosyncratic word clusters devolved with repetition into nonsense, nonsense that was nevertheless a reliable indicator of discomfort or displeasure. The mumbles flourished all through her teens. She and a perceptive friend spent hours once happily listing them, twenty or thirty utterances, each more bizarre than the last. „Cigar three, cigar three“, was one. Years later, her articulateness and communicativeness growing together, she explained how that began: it was „she got a three“ — a strikeout. So today I ask her about another one, equally mysterious: „We go on“. I’m putting some mumbles in the book about her, I tell her. Where did that one come from? She’s delighted to remember; she always is when we summon up remembrance of things past. It was from a Led Zeppelin song, she says. Another, „Dig a roof“, from a song she sang at camp. „Root?“ I suggest, searching, as usual, for meaning. No, she says, „roof“. If I knew the song, perhaps… I can guess it was, like a third strike, associated with something unpleasant, but I’ll never know how or why.

She reminds me of another mumble. We heard it often — back then we heard them all often. It sounded like „anklyeah“. She’s clear: there were no words hidden in that one. Rather, it represented the number seven. Leaving that oddity, I hazard another question: „You don’t mumble at work, do you?“ I’ve phrased it to invite the answer I want to hear, I know. Still, I’m delighted by the cheerful force of her reply. „No way!“

Because there can’t be mumbles. There mustn’t be. I remember the middle-aged woman I encountered in a bus station, mumbling under her breath to nobody at all — the frisson I felt, of pity but also fear. Jessy was still young; my imagination leapt ahead. Would she be like that, grown too old to be charming, still mumbling? If I felt fear, what could I expect from others? Higher-functioning people can learn from experience the necessity to control bizarre behavior — experience unlikely to be pleasant. Jessy needs explicit teaching. „You don’t want people to think you’re crazy, do you?“ I didn’t even know then if she knew what „crazy“ meant. Enough that she knew it was bad, that it included mumbles, and that if she tried hard she might learn to control them. And over years, she did.

Today, however, she is enjoying herself. She volunteers a mumble I’ve never heard her say, noting, with her usual precision, that it is „out loud, which is not really mumbling“. It’s out of the same bag of mysteries, though: „You caught my name“. Call?» I ask — her pronunciation is ambiguous and I know she hates us to call her name. But she’s definite; the word is «caught». Keep me from crying, she adds. «Crying makes my face all stuffy. I’m pleased. I’m proud». At forty, she’s developing her own method of control. If it works, who cares that it’s bizarre? For «crying» means the banshee wail, of all Jessy’s sounds the climactic worst. «Wee-alo, Wee-alo» it goes, up and down, up and down, in an ecstasy of desolation. It’s rare now, and brief, but still the same syllables, the same piercing, tuneless tune: our own domestic air-raid siren.

In the weeks spent writing this chapter, listening more closely than ever before, I’ve heard sounds I never noticed — within the squeal, for instance, the occasional squeak when Jessy’s task requires an extra application of force. How much else have I not registered? Her prosody is more complex than I thought. Experience must qualify those opening adjectives; her communications are not so much flat or atonal as unvarying; the impression of monotony is less a matter of unchanging tone as of tone that changes always in the same way. Tone and phrase are one package, inseparable. «Here’s the local forecast». It’s high on «Here’s», to catch our attention, then drops almost an octave. The prosody is as stereotyped as the language, as stereotyped as the situation (breakfast means we watch, must watch, the Weather Channel). «Mother». She’s brought my tea. That’s routine too, but to her mind less urgent; the tone drop is less marked, more like a major second. Her bedtime «Good night» is relaxed, almost musical; up on «Good», on «night» it descends to rest.

Every utterance has its own tune. «Ups-a-daisy doo doo doo!» marks annoyance. The voice waves up and down on «Ups-a- daisy», flattens out on the «doo’s». This exclamation point transcribes emphasis, not the confident enthusiasm of «Guess what! What happened? No big deal; she’s cooking, and „the bacon didn’t flip over“. A less transitory irritation yields something stranger, its tone blending annoyance with resignation: «Oh well, hang hang!» Then there’s «Oh I’m so sad!» There’s emphasis, but her voice is calm. She’s a little sad, but it’s under control. Another expression of sadness isn’t really an expression; it’s more like a claim. «Oh no!» This is Jessy’s regular response to disaster — earthquake, hurricane, train wreck, death. It may be in Canada or China; certainly it involves no one we know. Nevertheless, touchingly, Jessy will reach for the appropriate verbal package. Yes, it sounds fake. But it’s the best she can do.

Though disasters are common, oh no’s are relatively rare. Mostly they are elicited by newspaper stories, or conversation only partially understood. Jessy’s around during the TV news, but she pays no attention to the screen’s vivid horrors. They cannot pierce Nirvana. Yes, she may express irritation or sadness, she may experience the transitory desolation of wee-alo’s. But her language is who she is; I must insist on the primacy of that shining «Guess what!»

Yet this week I heard something even better. I heard her say, «Come see!» Common words, ordinary sounds, nothing bizarre about them. Words I had to wait forty years for. Come see. Share this experience with me. Together we will look at something with joint attention. It doesn’t matter what. I’ll write it down. And we will share the exclamation point.

Part two

Thinking

Chapter 5

«All different kind of days»

Scraps of paper are enough now, and a kitchen folder. In those days, though, the house was full of paper — notebook paper, construction paper, and more and more computer paper, the old n-by-14 sheets, lined or faintly striped, brought home by her father for a child who drew so much more easily than she talked. There was still little speech in those days; my language notes are largely from Jessy’s last twenty years. It was paper that allowed us to glimpse her mental experience, that assured us that though she might not talk, might not understand, she thought.

The records of her thinking fill not a folder but a heavy suitcase, and they are far from complete. Many disappeared at once into the whirlpool of a busy household. Some she cut up into the tiny squares we called her «silly business», to be sifted up and down, up and down, between her fingers. Still, opening that suitcase now, exploring it anew, trying anew to comprehend it, I am overwhelmed by the sheer volume of its contents. Alone, often by choice, sometimes by necessity (for however we worked to breach her isolation, someone could not always be with her), year after year she drew, she painted, she penciled her scraggly capitals and numbers, applying the simple skills we’d taught her to the materials we provided. I would come home, find new sheets, save them or lose them. It didn’t matter. Next day there would be others.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Exiting Nirvana»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Exiting Nirvana» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Exiting Nirvana» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Майкл Азеррад - Come as you are - история Nirvana, рассказанная Куртом Кобейном и записанная Майклом Азеррадом [litres]](/books/392533/majkl-azerrad-come-as-you-are-istoriya-nirvana-ra-thumb.webp)

![Эверетт Тру - Nirvana - Правдивая история [litres]](/books/399241/everett-tru-nirvana-pravdivaya-istoriya-litres-thumb.webp)