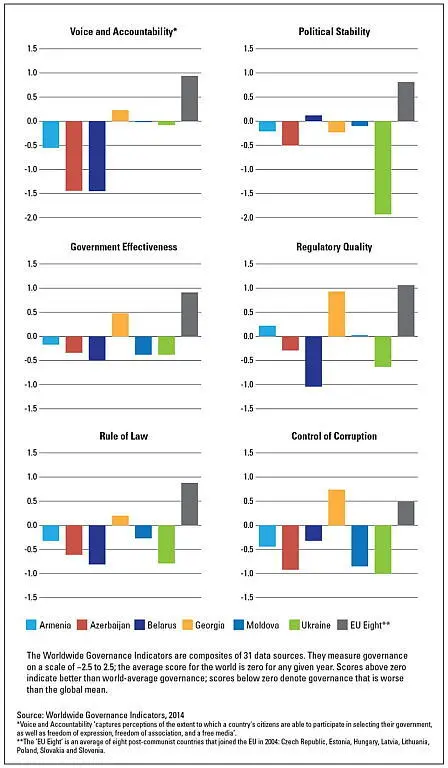

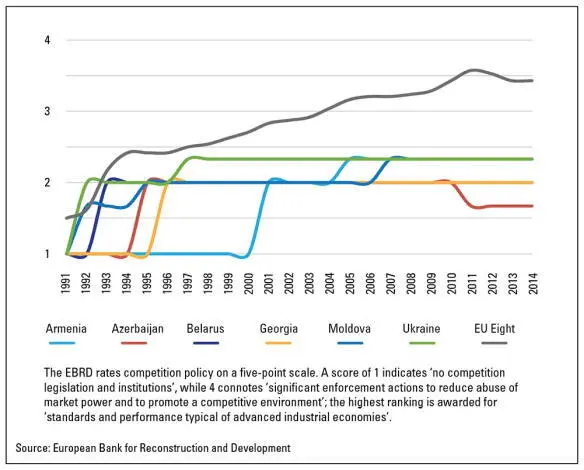

Figure 1: Governance

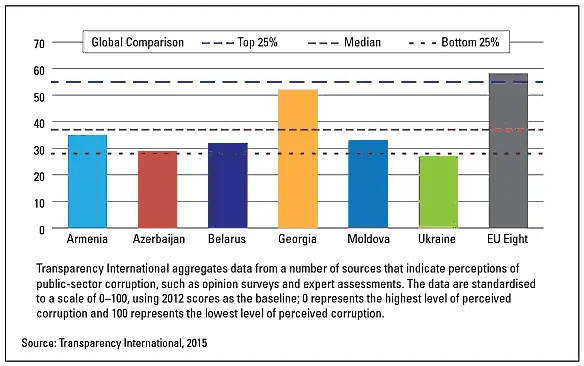

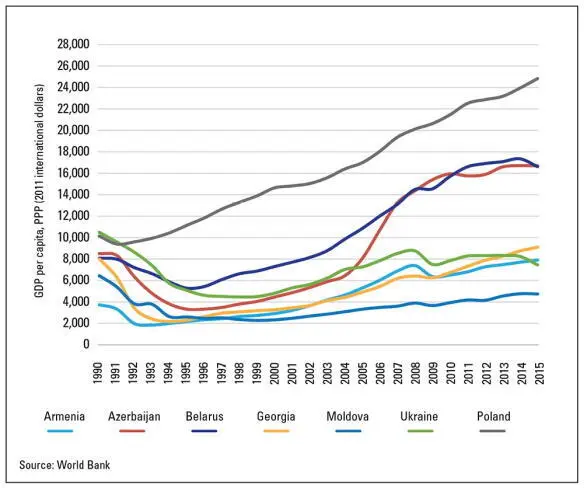

Figure 2: Corruption perceptions

Many factors contribute to these disparities. The contest between Russia and the West, while by no means the only one, did feed dysfunction in post-Soviet Eurasia in important ways. Firstly, it has helped sustain what Joel Hellman termed a ‘partial reform equilibrium’ in many of these countries. [42] Joel Hellman, ‘Winners Take All: The Politics of Partial Reform in Postcommunist Transitions’, World Politics , vol. 50, no. 2, January 1998, pp. 203–34.

Hellman noted that the post-communist countries that did not enact sweeping reforms early in the transition had, by the late 1990s, economies that concentrated gains among a small group of ‘winners’ at a high cost to society as a whole. The winners owed their wealth to the distortions and rents spawned by partial reform, and they used their economic power to ‘block further advances in reform that would correct the very distortions on which their initial gains were based’. [43] Ibid. , p. 233.

Hellman’s partial reform equilibrium has persisted in all six In-Betweens to the present day. Russian and Western willingness to subsidise political loyalty have played a part. Russia pours money into Belarus through waivers of oil-export tariffs and below-market gas prices; it was willing to demonstrate similar largesse to Ukraine under Yanukovych. The West has also played this game, often in breach of its policy of linking assistance to meaningful reform. Ukraine’s current US$17bn IMF programme is its tenth since independence; all previous ones have failed, in the sense that the Fund suspended lending because Kyiv did not implement the required reforms. Within 18 months of signing the current one, the IMF had to amend its by-laws to be able to continue dispensing funds. The notoriously corrupt Moldova would surely have gone bankrupt more than once without its EU lifeline. [44] The EU, the World Bank and the IMF froze financial aid to Moldova in 2015 following revelations about a bank-fraud scheme in which private financiers and public officials (including the prime minister) embezzled more than US$1 billion, or 12% of Moldova’s GDP. Transfers already authorised were not affected. The EU’s ambassador to Chisinau was quoted in 2015 as saying he was baffled by ‘how it is possible to steal so much money from a small country’ (quoted in Andrew Higgins, ‘Moldova, Hunting for Missing Millions, Finds Only Ash’, New York Times , 4 June 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/05/world/europe/moldova-bank-theft.html ). Nevertheless, as of September 2016 the EU had reopened the taps. See Cristi Vlas, ‘EU Commissioner Johannes Hahn Visits Moldova, Brings a €15 Million Assistance Program for Public Administration Reform’, moldova.org, 26 September 2016, http://www.moldova.org/en/eu-commissioner-johannes-hahn-visits-moldova-brings-e15-million-assistance-program-public-administration/ .

Following the 2008 war, Washington committed US$1bn in assistance to Georgia, a country of fewer than 5m people. These financial infusions, spurred on by the Russia–West regional contest, made it much easier for governing elites to postpone structural reform indefinitely.

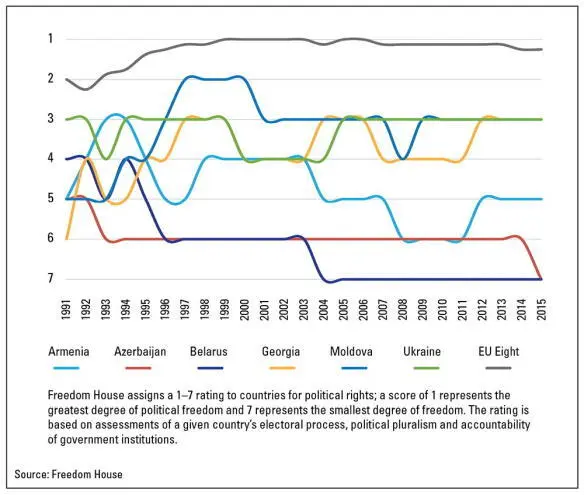

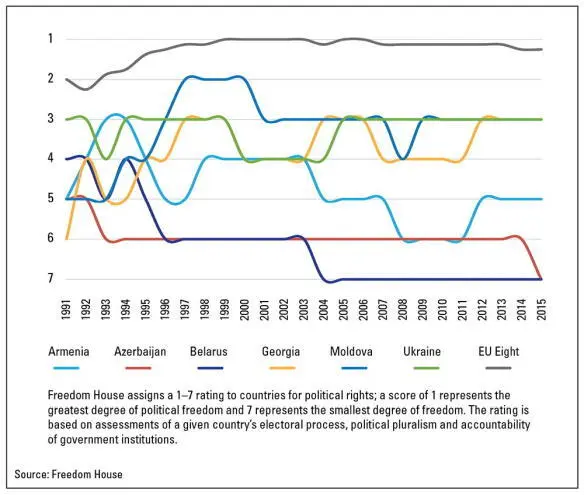

Figure 3: Political rights

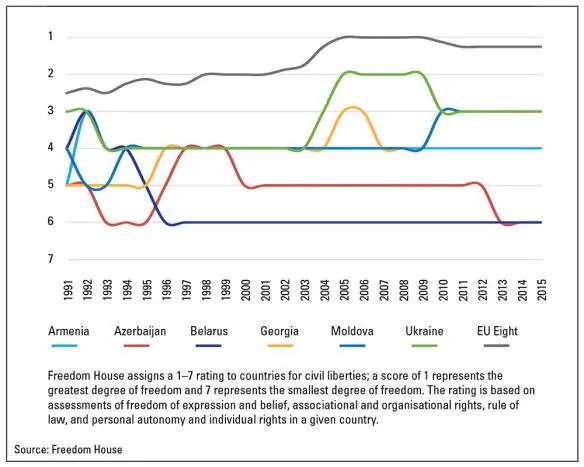

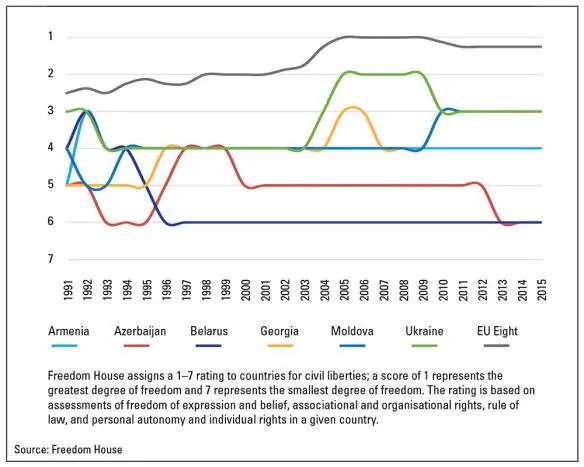

Figure 4: Civil liberties

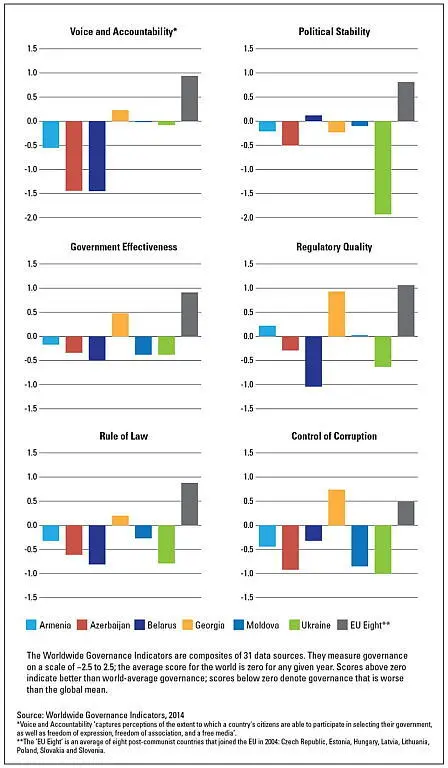

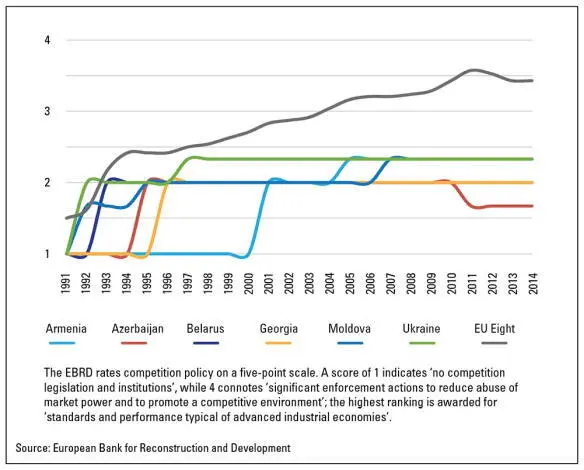

Figure 5: Competition policy

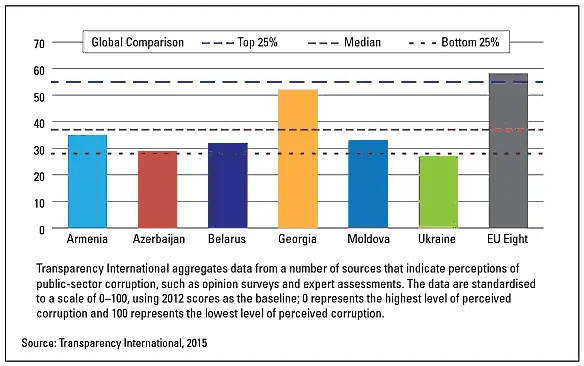

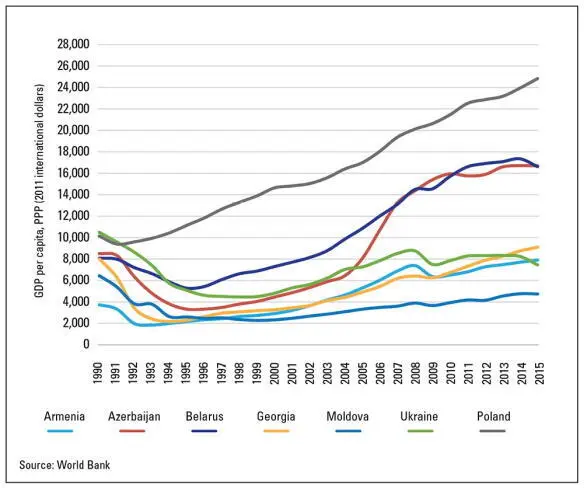

Figure 6: GDP per capita

Zero-sum policies on the part of Russia and the Western powers also exacerbated pre-existing political and ethnic cleavages in several of the In-Between states. In Ukraine, as noted earlier, the confrontation has mapped onto, and intensified, internal divisions over identity. Before the crisis, Ukrainians were split down the middle when asked if they would prefer membership of the EU or the Customs Union. The geographic breakdown within Ukraine was stark, with 73% in the western reaches of the country favouring the EU but 62% in the south and 46% in the east favouring the Customs Union in a 2013 poll. [45] International Foundation for Electoral Systems, ‘Ukraine 2013 Public Opinion Poll Shows Dissatisfaction with Socio-Political Conditions’, 5 December 2013, http://www.ifes.org/news/ukraine-2013-public-opinion-poll-shows-dissastisfaction-socio-political-conditions .

After the Crimea annexation and the war in Donbas, the balance shifted somewhat, but regional schisms regarding NATO and EU membership remain. [46] See polling in Steven Kull and Clay Ramsay, ‘The Ukrainian People on the Current Crisis’, Public Consultation Program at the Center for International and Security Studies at the University of Maryland Report, March 2015, http://www.cissm.umd.edu/publications/ukrainian-people-current-crisis .

In Moldova, there are multiple axes of cleavage. Transnistria residents, survey research has consistently revealed, would prefer to become part of Russia than to reunify with Moldova. [47] For evidence from 2014, see Gerard Toal and John O’Loughlin, ‘How People in South Ossetia, Abkhazia and Transnistria Feel about Annexation by Russia’, Washington Post Monkey Cage Blog, 20 March 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2014/03/20/how-people-in-south-ossetia-abkhazia-and-transnistria-feel-about-annexation-by-russia/ .

Even in government-controlled territory on the right bank of the Dniester River, Moldovans are divided; as of October 2015, 45% favour joining the EEU over 38% who prefer the European Union, and the EEU has been gaining ground. [48] International Republican Institute, ‘Public Opinion Survey Residents of Moldova, September 29–October 21, 2015’, http://www.iri.org/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/2015-11-09_survey_of_moldovan_public_opinion_september_29-october_21_2015.pdf .

The November 2016 election of a president who favours closer ties with the EEU shows the strength of pro-Russian sentiment, although his narrow margin of victory demonstrates the persistent divisions in Moldova’s society on these matters. The Gagauz are also far more Russophile than the population as a whole. [49] According to a disputed plebiscite conducted in February 2014, more than 98% of the Gagauz supported joining the Customs Union. See ‘TsIK Gagauzii obnarodoval okonchatel’nye itogi referenduma o budushchei sud’be avtonomii’, TASS, 5 February 2014, http://tass.ru/mezhdunarodnaya-panorama/940951 .

As in Ukraine, being caught up in the Russia–West battle royal weakens social cohesion and sharpens ethnic and political divides, holding back market reforms and damaging fragile democratic institutions.

In Georgia, there have been similar gradients in opinion between the separatist territories and the rest of the country. Georgians in government-controlled areas are by a long shot the most pro-NATO and pro-EU in post-Soviet Eurasia. [50] In a 2016 poll, 79% of Georgians favoured NATO membership and 85% membership of the EU. See International Republican Institute, ‘Public Opinion Survey Residents of Georgia, March–April 2016’, http://www.iri.org/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/georgia_2016.pdf .

South Ossetia residents are overwhelmingly in favour of becoming part of Russia, and Abkhazians are strongly pro-independence and anti-NATO. [51] Toal and O’Loughlin, ‘How People in South Ossetia, Abkhazia and Transnistria Feel about Annexation by Russia’.

Even before the 2008 war, these rifts bedevilled activities to reconcile grievances stemming from the conflicts of the early 1990s. Today, Russia’s determination to prevent Tbilisi from restoring control over the breakaway regions prevents any such activities from even getting off the ground. Until the late Soviet period, Georgians and Abkhaz lived in Abkhazia in relative harmony. Following the ethnic cleansing of Georgians from Abkhazia in 1992–93, a full generation of Georgians and Abkhaz have grown up without contact with each other; it is not likely that their children and grandchildren will have any such opportunity.

Читать дальше